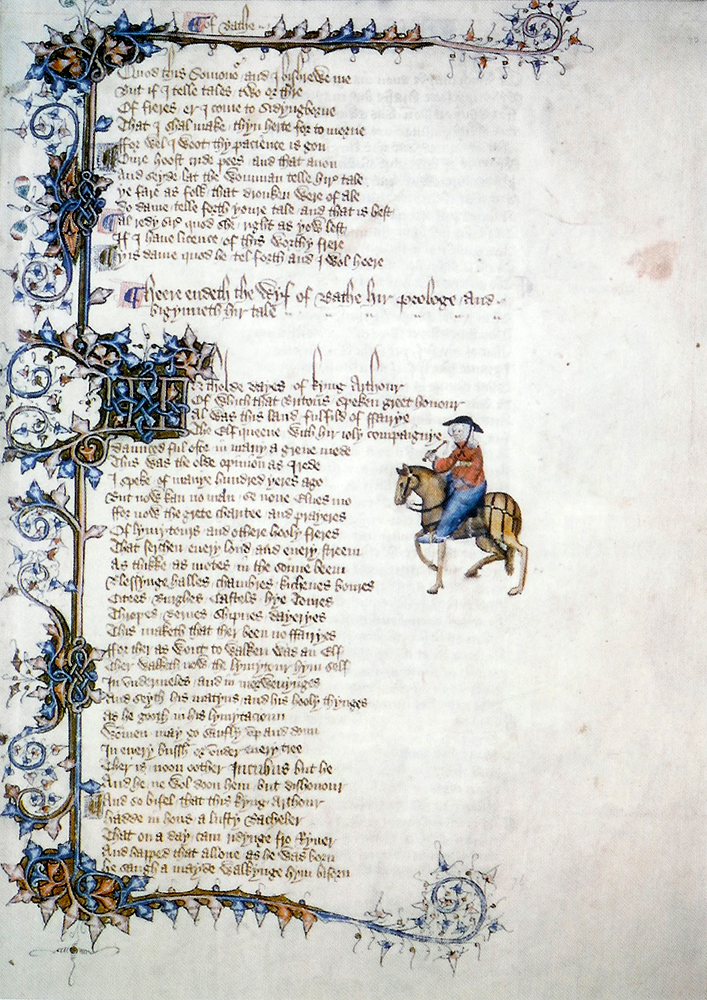

19 Canterbury Tales: The Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale

|

Introduction

by Denise Williams

The “Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale” was written at a time when the social structure of England was evolving, allowing for a merchant class to emerge of which the Wife of Bath is a prime example. The story provides insight on women’s roles in the Late Middle Ages when they could occupy only three stations in society: maiden, widow or wife. The Wife of Bath is unique in this context: as a childless widow, she has inherited her husbands’ wealth (as property was passed down to sons even if their mothers were still alive) which allows for more autonomy than other women of the time. The character in this story was one of Chaucer’s most developed with the prologue almost twice as long as the actual tale itself; it is remembered as one of the best-known in the collection. She calls herself “Alys” and “Alyson” though this is also the name of a friend she references and various other characters throughout the Tales which causes confusion for students and scholars alike.

Prologue

In the Prologue, we learn some important information about the Wife of Bath, namely that she has been married five times and therefore will be speaking about “wo that is in mariage.” She quickly recounts her first three marriages, to older men, starting at age 12. Her fourth marriage was to a philanderer who she repaid by making him believe she, too, had been unfaithful. The fifth marriage is to a younger man, Jankyn, who is physically abusive (his beatings leave her deaf in one ear) and an unrepentant misogynist; they get into a heated argument when she tears some pages from his copy of the “Book of Wikked Wyves” though, after this, he concedes his power to her in the relationship. She is then interrupted by the Friar who complains of the “long preamble” she has provided. As a widow five times over, she would have been seen as a “loathly lady”–a woman who remarries in order to satisfy her sexual desires (something the Church equated with bigamy at the time). But the Wife of Bath knows the stories of many holy men who have had multiple wives and her adept appeal to the Scriptures puts her in direct conflict with the teachings of clerics. In her opinion, her history of multiple marriages has made her an expert on marital relations, and certainly more so than celibate, male clergy. The Wife of Bath argues, above all, that women are morally identical to men which contradicts the prevailing double standard of her era.

Summary of the Tale

The tale starts off with this Knight who has raped a young woman and for some reason the Queen wants to give him a chance to redeem himself. King Arthur wants to kill the Knight but then decides to leave this punishment in the Queen’s hand. The Queen gives the Knight twelve months and one day to bring back the answer to the question “what do women most desire?” If the knight can’t find the answer to the question then he will be killed. He sets out on a long journey to find the answer to the Queen’s question. He asks many women and many an answer he receives; none of which have set well with the knight. The last has come to find what he is in search of and he still is bewildered. He comes upon this old, ugly lady who tells him that she has what he is searching for and he will pay for her wisdom. She gives him the answer to the question and shares it with the Queen. She is pleased and releases him so his life is spared. The old lady wants the handsome knight to marry her and he gave his word that he would do whatever she asked of him. They marry and the knight is miserable and treats her terribly. On their wedding night, the old woman is upset that he is repulsed by her in bed. She reminds him that her looks can be an asset—she will be a virtuous wife to him because no other men would desire her. She asks him which one he would prefer—a wife who is true and loyal or a beautiful young woman, who may not be faithful. The Knight responds by saying that the choice is hers. Knowing that she has the ultimate power now, him giving her full control, she promises beauty and fidelity. The Knight turns to look at the old woman again, but now finds a young and lovely woman. The old woman makes “what women want most” and the answer that she gave true to him, sovereignty (“Wife of Bath’s Tale”).

Works Cited

“Wife of Bath’s Tale.” Wikipedia, 12 Apr 2020. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Wife_of_Bath%27s_Tale Accessed 13 Sept. 2020.

Discussion Questions

- What “class” does the Wife of Bath belong to? How do you know?

- Is this character a proto-feminist? Or is Chaucer writing an inherently anti-feminist text here?

- She has many counter-arguments to the prevailing ideas about women of her day (usually introduced with the phrase “Thou sayest”). What arguments are these? What evidence does she provide?

- There are very few women in Canterbury Tales; how does Wife of Bath compare to the other “major” female storyteller (The Prioress)?

- How does the Tale she tells relate to the information in her Prologue?

- Who holds power in “The Wife of Bath’s Tale”? Do those who have power use it correctly?

Further Resources

- An essay chapter from the Open Access Companion to the Canterbury Tales on “Love and Marriage in the Wife of Bath’s Prologue”

- A video of David Wallace, author of Geoffrey Chaucer, discussing Wife of Bath

- An animated video of the “Wife of Bath’s Tale.”

Reading: The Wife of Bath’s Prologue

|

|

lines 35-82: The Wife of Bath’s opinion about marriage and virginity

|

|

lines 83-100: About St. Paul’s virginity

|

|

lines 101-120: About virginity in general

|

|

lines 121-140: The purpose of the genitals

|

|

lines 141-168: How a husband should pay his wife

|

|

lines 169-193: The Pardoner’s interruption

|

|

lines 194-229: About the Wife of Bath’s five husbands

|

|

lines 230-240: About the art of lying

|

|

lines 241-262: The Wife of Bath on how to lecture a husband

|

|

lines 263-290: A shrewe’s proverb

|

|

lines 291-308: A wife is no horse and cannot be tested

|

|

lines 309-329: Envy and the power of gold

|

|

lines 330-342: Sexual favour and the power of gold

|

|

lines 343-353: The Wife of Bath rejects austerity and frugality

|

|

lines 354-362: The Wife of Bath compared to a cat

|

|

lines 363-384: Bondage in the marriage band

|

|

lines 385-400: About cheating

|

|

lines 401-436: Envy, payment and …

|

|

lines 437-456: … pleasure

|

|

lines 457-474: The Wife of Bath claims the right to drink

|

|

lines 475-486: About youth and aging

|

|

lines 487-508: The Wife of Bath’s fourth husband

|

|

lines 509-530: The Wife of Bath’s fifth husband and the market price of sex

|

|

lines 531-548: The Wife of Bath’s gossip

|

|

lines 549-592: The Wife of Bath tells how she has enchanted her servant

|

|

|

|

lines 593-632: The funeral of the fourth husband

|

|

lines 633-652: The servant becomes the Wife of Bath’s fifth husband

|

|

lines 653-716: Old men should read and write, young men should play with their wives

|

|

|

|

lines 717-793: The fifth husband reads about the vices of women and lectures the WoB

|

|

|

|

lines 794-834: Irritation, anger, a fight, deafness and a happy end

|

|

|

|

lines 835-862: The dialogue between the Summoner and the Friar

Biholde the wordes bitwene the Somonour and the Frere.

|

|

|

|

Reading: Wife of Bath’s Tale

Heere bigynneth the Tale of the Wyf of Bathe.

|

|

lines 888-904: A rape, a penalty, the queen judge

|

|

lines 905-918: The queen sends the criminal knight on a quest

|

|

lines 919-957: The knight searches the land

|

|

|

|

lines 958-988: Ovid’s tale about Midas: a women cannot keep a secret

|

|

lines 989-1014: The knight’s last chance

|

|

lines 1015-1036: The knight gives his word

|

|

lines 1037-1051: What women want most of all

|

|

|

|

lines 1052-1078: The fulfilment of the knight’s promise

|

|

|

|

lines 1079-1109: A frugal wedding

|

|

lines 1110-1130: Jesus on the origin of gentility

|

|

lines 1131-1170: Dante on the origin of gentility

|

|

lines 1171-1212: Reflections on poverty and gentility

|

|

lines 1213-1241: The two choices of the knight

|

|

|

|

lines 1242-1270: A happy end

|

|

|

|

Heere endeth the Wyves Tale of Bathe

Source Text:

Kökbugur, Sinan, ed. The Canterbury Tales (in Middle and Modern English). Librarius.com, 1997, is copyright protected but reproduction expressly allowed for non-profit, educational use.

![]()