1 Volume I, The Early Years

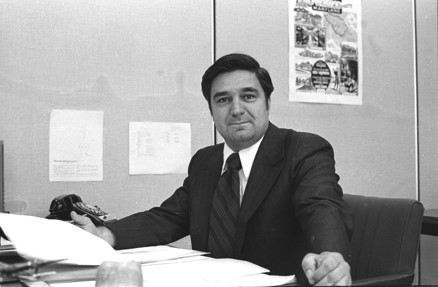

Vladimir Marinich

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface

Even Before the Beginning

The Beginning

Getting Into the Systems Approach

We Were Small, but Burgeoning

The Change Agent

Programs, Nature Walks, and Growth

Accreditation

The College and the Evaluation System Grow

MBO’s and All That Stuff

There Was More Than MBO’s

1976 Started Out Well

Enter the Press

Changes in the Late ‘70’s

’78 Rocked!

And So Did ’79

Nearing the End…of the Beginning

Smith’s Legacy

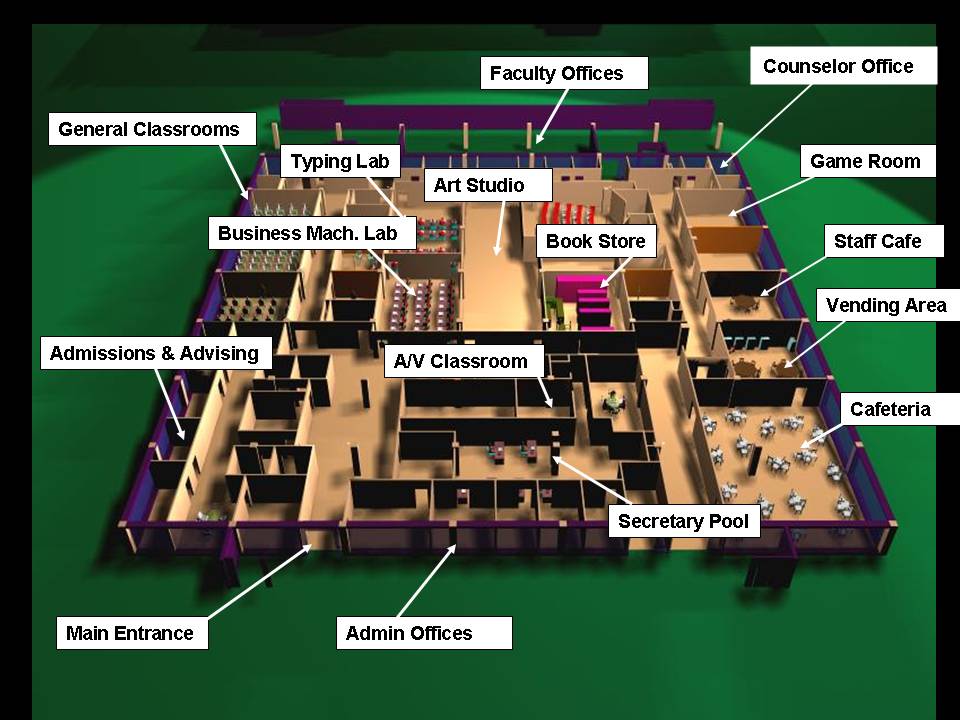

Appendix I Three-dimensional Rendering of HCC’s First Building

Appendix II HCC Staff Who Went on to Presidencies/Chancellorships

Appendix III Chronology of Public High Schools in Howard County

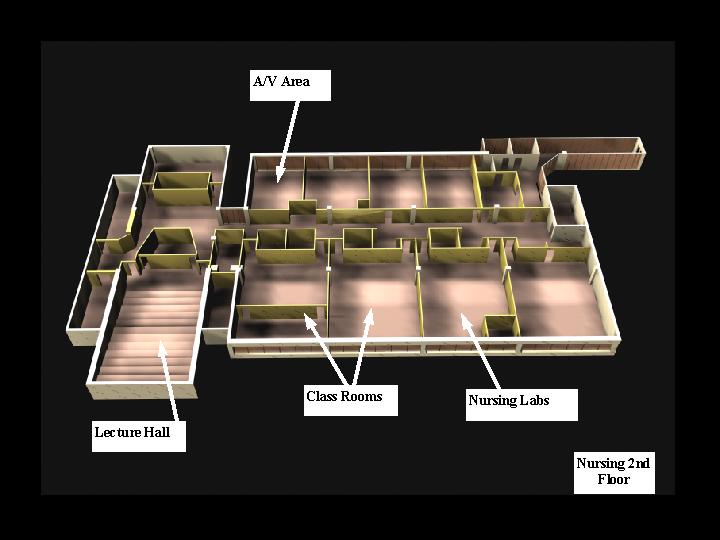

Appendix IV Three-dimensional Rendering of the Nursing Building

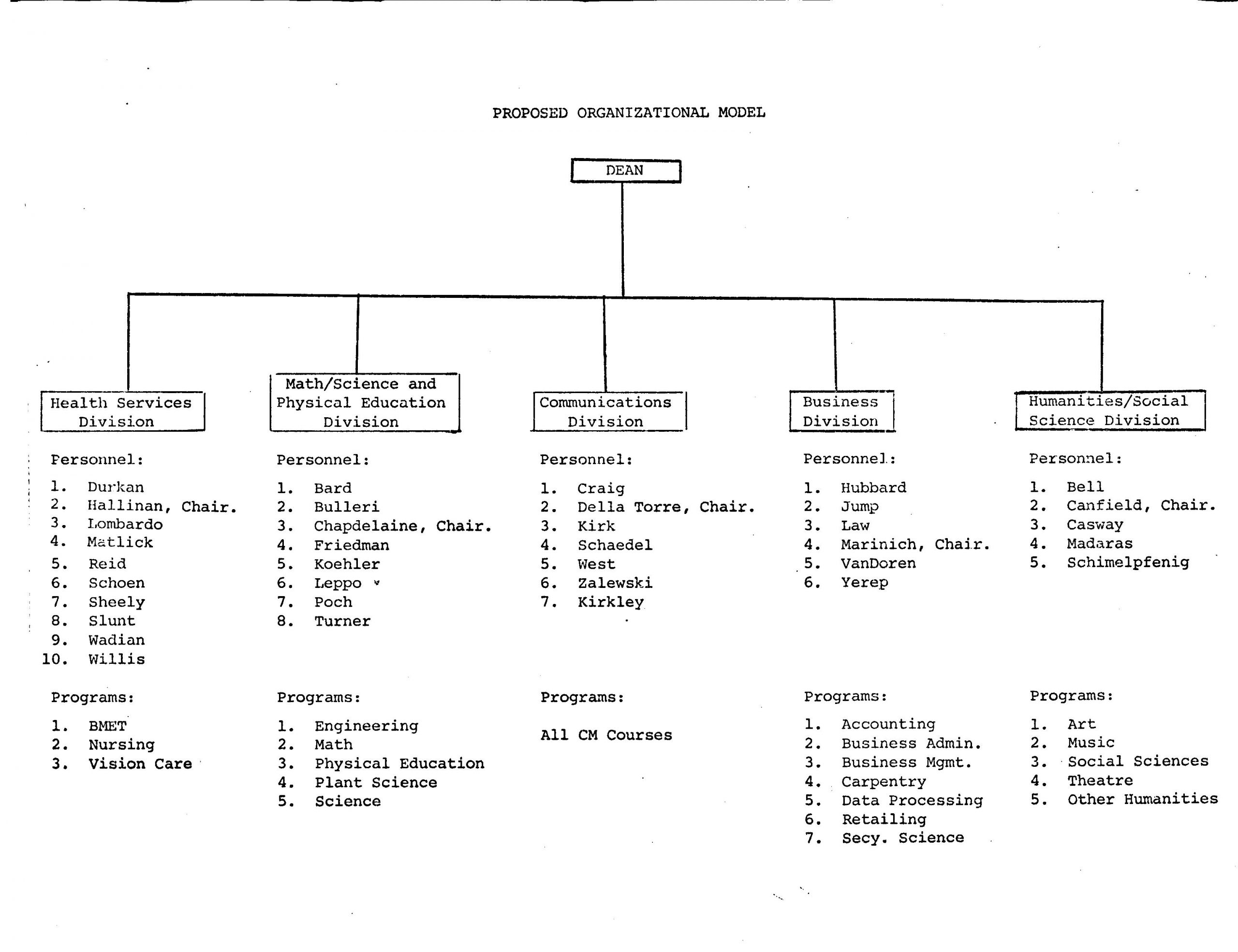

Appendix V Proposed Organization Chart, 1978

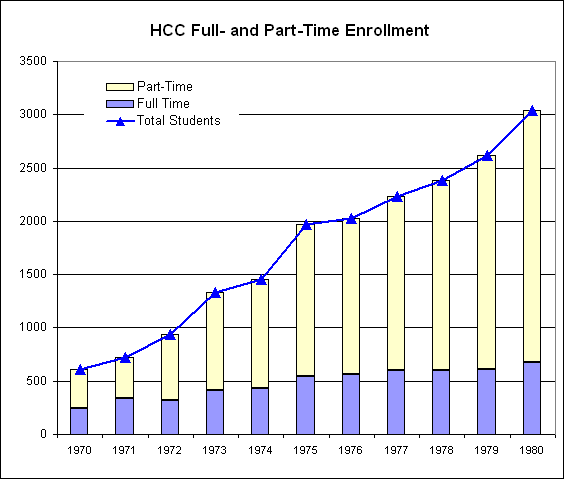

Appendix VI HCC Full- and Part-Time Enrollments, 1970 – 1980

Endnotes

PREFACE

This history of Howard Community College was made possible by a sabbatical leave of one semester in the spring of 2006. The prior year I was given time to work on the HCC archives and this allowed me to research and gain even more knowledge of HCC’s past, but in doing this, the more I found out, the more there was still to find out; so, the problem was not in having enough material, it was condensing what seemed to be, on occasion, too much material.

I got to work on archival materials in the prior year, but I wasn’t the first. My colleague and friend, Larry Madaras, began the process. In his last semester at HCC, I worked with him on some parts of archival materials, and when he retired in December 2004, I took over the project; but I didn’t do it alone. There were several other dear colleagues who were part, and partners, in what we did in 2005. Four major areas of activity were seen as necessary; one was the collection and organization of official college materials – all the catalogs going back to year 1, student handbooks, annual reports, bylaws, policy documents, Board Minutes, student newspapers, enrollment reports, course schedules, you name it! There was no central repository for these materials, so HCC established an archive and hired Norah Burns to do much of this work. I gladly assisted her where I could, and continue to do so. A second area was regional and local newspapers. Over the past year we have been going through all the newspaper articles and clippings that had been saved by the college to determine what was salvageable. While these newspaper articles provide a wealth of material, unfortunately some of them have deteriorated to where they cannot be scanned or photographed. In some cases there were multiple copies of the same article and we had to choose the copy that was physically the best. And sometimes the best copy was not all that good.

A third source of information was the HCC documents of various kinds; memos, letters, minutes of various committee meetings, and various other college publications that did not always fit into any particular category, of which there were quite a few, and many of these publications were not produced on a continuing basis and often enough the name of the publication changed. Fortunately, a lot of this information has survived, and that is good. However, in some instances there are gaps. So, for example, in this narrative I refer to the enrollments of the summer session, 1975, as the first mention of HCC’s summer classes. It is not clear whether previous summers’ enrollments have been lost, or whether they have not yet come to the attention of the archives. In other words, we do not have previous summers’ data.

The fourth area that needed serious attention was photographs. Over the thirty six years of the college’s existence there have been tens of thousands of photographs taken of various locations, buildings, classrooms, events, and individuals (faculty, staff, students, community residents, leaders, and visiting dignitaries). It was important to identify as many of these as possible and to categorize them in terms of when the picture was taken, who was in it, what was the location and event, and selecting the best copy of the picture, where multiple shots were taken, to keep and digitize. The approach was to have a team do this. It could never have happened without Quent Kardos, the head of HCC’s A/V Department. His ability and skills were indispensable. Norah Burns recorded all the information as we reviewed one photo at a time and set up the data base. Dr. Peggy Mohler of the Grants Office was invaluable for her knowledge of the college and the community. These are the “superheroes.” I am on the team as the “college historian” who can often tie together individuals, events, and locations of a photo to give it greater clarity in identifying it. From time to time other colleagues joined our review sessions to help with identifying photos. Over the past year and a half the team has reviewed approximately 17,000 photos and identified about 1,900, and there are probably just as many, if not more, still to review.

This brings me to a fifth source of information; oral communication. Larry Madaras conducted a number of interviews that were recorded and transcribed. They are part of the historic database, as are the ones that I have done. I have, however, also gotten comments from colleagues in informal settings about various past people and events. These comments came from folks who are part of the history of HCC, some of whom are still here, and their comments are sincere views of past events as they experienced or perceived them. In some instances the same events were seen completely differently by two different people. I have heard these words and terms used about past events: “watershed moment,” “defining moment,” and “crisis.” On the other hand the same events were seen by others as “unimportant,” and “what are they talking about?” While this kind of information was interesting, I could only use it if there was a clear pattern in its understanding by more than just one or two people. Consequently, the major source of information in trying to present the history of HCC is documentary evidence that includes memos, minutes, reports, samples of faculty work, newspaper articles, and planned interviews for anecdotal information.

One of the challenges in developing this history was that the archives were, and still are, in the process of development and organization. As a result, much of the information that I was able to glean was not from organized or catalogued sources. This is not an attack on the archival project, since I have been assisting in that area, but simply recognition that this history project was being developed as the archives were being developed. Consequently, as I was writing the history I was finding more things that needed to be included, but I eventually had to stop adding newly discovered pieces of information, otherwise the research would go on forever and this document would not get produced.

All historical writing is interpretation and narrative. This means that historical writing is the telling of a story and, in doing so, one uses the best, most thorough, and most accessible information that is available. I think that I have described the information that I gathered, and I have tried to exercise care in presenting a balanced story of HCC. This is not the history of the community college movement with HCC as an example of such a national movement. Rather, this is the story of one school’s origins and development as experienced by the community, students, and staff of the college. This brings me to the final point about this project. For those of you who like to read the last chapter of a book to see how it ends, and prefer not to deal with everything in the middle, I will tell you up front how this history project ends. It is the story of an ongoing success that started over 40 years ago.

There are quite a few folks who deserve my thanks and appreciation. Larry Madaras started the ball rolling and when he knew that he would be retiring he gave me a lot of the materials that he had collected and developed (and if you know Larry, the word “collected” is an understatement). He was also very supportive of me continuing this work. Dr. Mary Ellen Duncan, HCC’s President, encouraged me and, just by being herself, she showed me that she had faith in my being able to accomplish this project. Our Academic Vice President, Prof. Ronald Roberson, gave me time to work on the archives, and this was really an important foundation for getting HCC’s history written. I needed time to put the information together and to write the history, so I applied for a sabbatical leave. The Chair of the Social Sciences Division, Dr. Jerrold Casway, supported my application and wrote a very strong recommendation on my behalf. I appreciate this support very much. My getting a sabbatical leave was great for me, but it put quite a burden on Jerry’s shoulders. He had to staff the courses that I normally teach, and as anyone who has had to locate and hire adjunct faculty knows, this is no easy chore. The Sabbatical Leave Committee recommended my leave and sent it up through channels. The Board of Trustees approved. So, to all of you, I extend my appreciation and gratitude.

As the manuscript progressed, I asked Dr. Alfred Smith, the first president of HCC to look over the forty eight pages that I had written up to that time. He responded and made some comments and observations that were helpful. As the manuscript came to an end I wrote to Dr. Smith asking if he would be willing to review the completed manuscript; however, I have not heard from him as yet.

Joetta Cramm, who I believe could rightly be considered as Howard County’s historian, reviewed the work and responded. I appreciate her several observations and questions. Larry Madaras also got the completed manuscript and offered a number of helpful observations.

I marvel at the magic that my colleague Professor Dave Hinton can work with computer images. He produced the three-dimensional renderings of the first building and of the Nursing Building. I thank him for his generosity of time and effort.

I have to mention Norah Burns and Quent Kardos again. To use an expression that we hear our younger students employ all too often, Norah’s and Quent’s competence, professionalism, dedication, and support has been “totally awesome.”

My colleague, Dawn Malmberg, made this HCC History look good by doing all those things that make this document look professional. Her skills never cease to amaze me. Thanks, Dawn!

My colleague at HCC, and my wife, Barbara Livieratos, read this material and gave me suggestions and ideas for accuracy of expression, general layout, editing, and gave me lots of encouragement and constructive criticism. Much thanks to you, Barbara.

EVEN BEFORE THE BEGINNING

Howard Community College’s history, growth, and success are obviously linked to the growth of Howard County and to the development and growth of Columbia. In October 1963, The Rouse Company announced that it had acquired some 14,000 acres in Howard County for the purpose of building a planned city.1

By May 1965, the planning of Columbia had progressed to the point that on May 28-29 a meeting was held of the “College Advisory Group for Columbia” in the Village of Cross Keys.2 Some time before this meeting, perhaps in 1964, James Rouse had already been thinking about “educational facilities over and above the senior year in high school.”3 Rouse wondered about the type of post-secondary education in Columbia. “Should we have a two-year junior college, or a four-year liberal arts college? Or do we move toward a trimester system that would make it possible for a student to receive a BA degree in three years? Another possibility might be to encourage the establishment of a public junior college in Columbia, and then add a private ‘senior college’ for junior and senior year on a trimester system.”4 Rouse continued by mentioning vocational education, adult education, and life-long learning as major elements of “the fullest possible development of an individual.”5

While this was going on, the Howard County Board of Commissioners (this was several years prior to the charter that created a County Council) and the county’s Board of Education began to think seriously about a community college. The majority of Howard County college-age students who went on to a community college went to Catonsville Community College. Dr. Edward Cochran, who was on the Howard County Board of Education in the 1960’s, estimates that this majority was about 90%.6 The two problems that Howard County faced with this arrangement was that the state and county were picking up the equivalent of out-of-county fees, and Catonsville Community College would contact Howard County each year “about whether or not they could take the students for the following year.”7 This was not the most stable of conditions to operate under year after year; so, in 1965 a committee was formed to look into the possibility of a community college in Howard County.

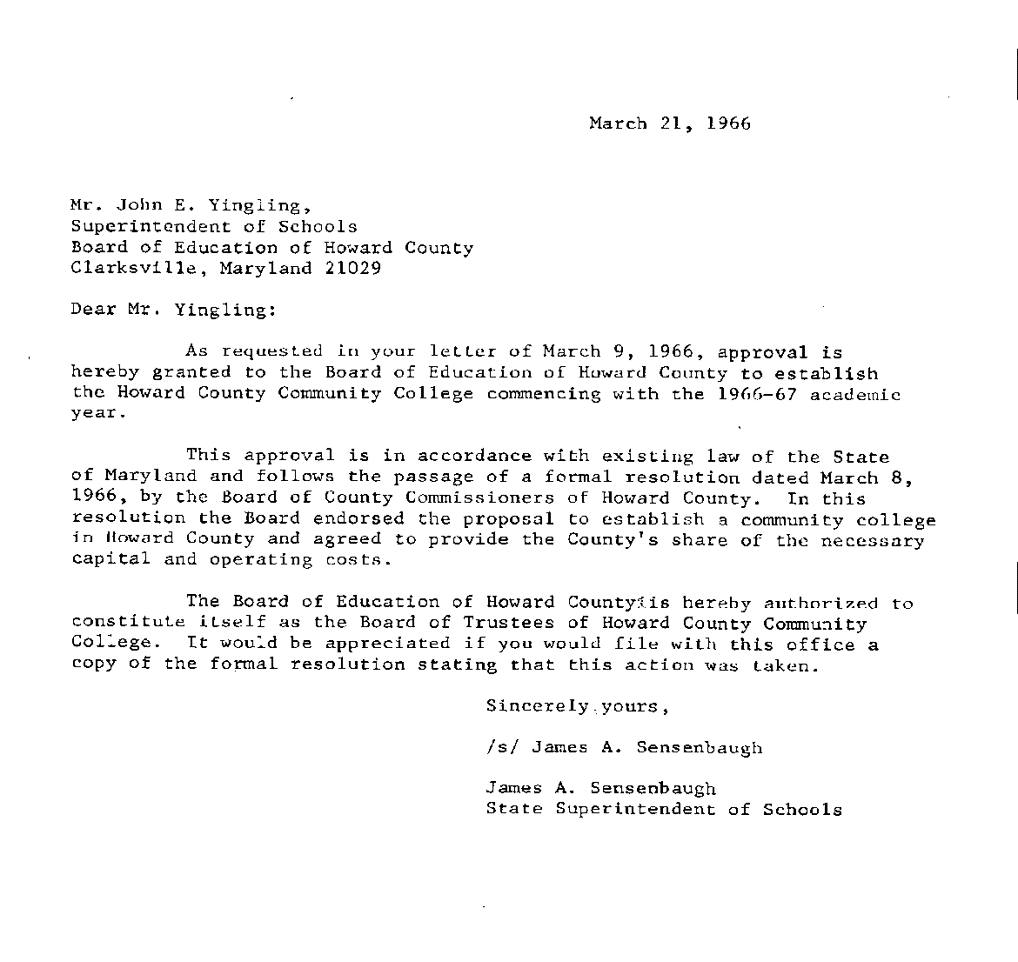

In October 1965, after meetings with the Maryland State Department of Education, the Board of Education “passed a resolution indicating intention to form a community college and move forward with that project.”8 The original thinking was to open the college in 1967 with classes to be held in one of the existing high schools with late afternoon and evening classes.9 The County Commissioners authorized the Board of Education to be the college’s Board of Trustees, and on March 18, 1966, Howard Community College received authorization by the Howard County Commissioners. Three days later the State of Maryland approved the establishment of the college. Howard Community College would be the fourteenth community college in Maryland.

By 1966 Howard County had evolved from being primarily an agricultural county to one that was suburban, and exurban the farther out that one went. The western part of the county was still very much agricultural. Route 29 was a two-lane road and Route 40 had none of the sprawl of strip shopping centers, gas stations, or fast-food places, and the closest McDonald’s was inside the Baltimore city line. The county, as already mentioned, was run by Commissioners, and there were 4 public high schools; Atholton, Glenelg, Howard, and Mt. Hebron. There was also one private nonsectarian school, Glenelg Country School that opened in 1954, although the high school portion of the school did not begin operations until 1985 and did not see its first high school graduation until 1989. In 1966 the population of the county was about 50,000, and Ellicott City was the historic county seat. In other areas of American society, the book world saw the publication of Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood,” and American theatre was enjoying “Cabaret.” Walt Disney and Montgomery Clift both died in ’66, and entertainers Halle Berry, Salma Hayek, and Chris Rock were born.

The ultimate location of the site for the future community college was not without discussion and debate. Cochran recalls, “the Rouse Company had a particular site to recommend to the Board, and the other folks who thought it should be in Ellicott City or whatever did not have specific sites. They just had a feeling that it ought to be somewhere else.”10 The Rouse Company’s recommended site may not originally have been where the college now stands. Again, Cochran also recalls that the Rouse Company had other plans for the frontage on Little Patuxent Parkway; The Rouse Company wanted the front of the college, along Little Patuxent Parkway, to be reserved for commercial properties. The Board refused to agree to this, and the Rouse Company eventually relented.11

The site for the college was finally accepted and in June 1966 the land was purchased for $300,000. Thus, the myth that the college got the land for $5 is just that, a myth or, in today’s parlance, an urban legend. The breakdown of the cost was that the county and federal funds would each pay 25%, and the state would pick up the rest. There was also some discussion that the location of the college in this area near Columbia’s future downtown would place it “adjacent to the ‘future private college’ expected to be built in Columbia.”12

The projected opening of the college for 1967, with classes in high schools was postponed when the Board of Trustees was informed in late 1966 that Catonsville Community College would be able to continue to take Howard County’s students. As a result, the Board decided to plan for a campus and an opening date of Fall 1970.

Early in 1967 Dr. Joseph Hankin, President of Harford Community College, was hired as a consultant to help the Board with its planning of the college. The Board requested $1,630,000 from the state and $1,450,000 as a bond issue. These funds were used for the construction of the first building of the college.

The first phase of the college’s construction was to have a main building and a fully equipped gymnasium; however, the architects for the college, Perkins and Will, a Washington based organization, reported to the Board of Trustees that “preliminary studies of the site and the most recent figures available on site preparation costs in the area indicate that the original estimates for site work were low. In order to follow the Board’s instructions to stay within the approved budget, the architects feel that it will be necessary to consider omitting the original plans for a fully equipped gymnasium.”13 The ultimate plan, though, was that the first building was to be part of a future complex that would be developed over several years.

The Howard County Community College anticipates an enrollment of almost 1,800 students by 1975, at that date, an estimated $8,000,000 will have been spent on campus facilities, including a five-story, 75,000 volume library, and an auditorium with a seating capacity of 2,000.14

The memorable world event of 1969 was Neil Armstrong setting foot on the moon. On the national scene, Richard Nixon was into the first year of his presidency with his vice president, the former governor of Maryland, Spiro Agnew. At the movies, the film to see was “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” Hollywood lost Judy Garland that year, and everyone was reading the blockbuster novel, “The Godfather.” That summer saw a lot of activity in Howard County and Columbia. A groundbreaking ceremony for the college was held during the week of June 22. That same week a groundbreaking ceremony was held for the first Interfaith Center to be built in the Village of Wilde Lake; The Rouse Company announced that it was moving their corporate headquarters from the Village of Cross Keys in Baltimore to Columbia, and would be housed in the new American Cities Building; and local residents protested the size of a Seven-Eleven store’s sign in Columbia to the Howard County Planning Board.15 Jim Rouse’s grandson, Edward Norton, was born. Norton grew up in Columbia, and would become a well known film actor.

Howard County was not the way it is today, and Columbia certainly was not either. Route’s 29 and 40 have already been mentioned. And the only movie theaters were the Westview Cinema and Edmondson Drive-In, which seemed very far away from Columbia. Of course Columbia in late 1969 and 1970 was quite small. The Villages of Wilde Lake, Oakland Mills, and Harper’s Choice existed, as did the Longfellow neighborhood. Swansfield was just being built. Sewell’s Orchard was just that – an orchard where one could go to pick and buy fruit and berries. And, as for the rest of the villages and neighborhoods of Columbia, they were still in planning stages or very early development.

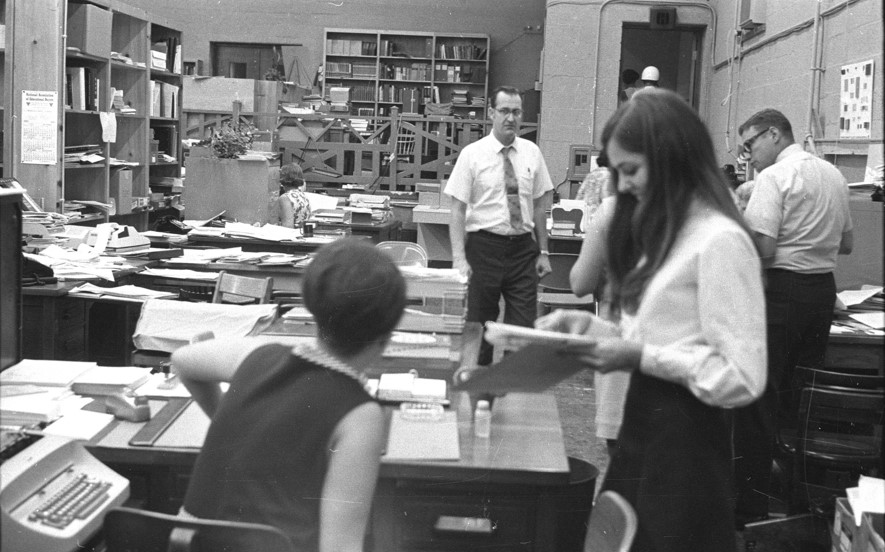

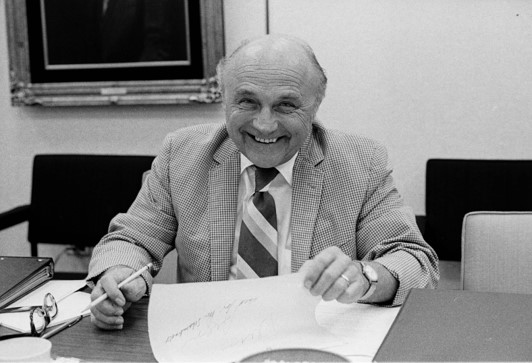

The president of the college was Alfred J. Smith, Jr. He had earned his M.A. from Columbia University, Ed.D. from Indiana University, and had most recently been at Corning Community College in New York, where he began as a faculty member teaching business courses, advanced to Chair of the Business Department, and was most recently the Academic Dean at Corning. Donald Forsythe, who had been the Dean of Continuing Education at Corning Community College, thus having been Smith’s colleague in New York, was hired by Smith to be the Dean of Faculty (a title that was to be changed a few years later to Dean of Instruction). The Dean of Community Service was Joseph DeSantis who had come from Niagara Community College. The Librarian was Mrs. Elizabeth Siggins, and the Director of Administration was Mr. Darrell Campbell. The offices of these first people were in the old gymnasium area of the Board building.

Smith, who had been hired in mid-1969, had more than his share of work to do between his start as president and the opening of the school that would happen just a little over a year later. The schedule and progress of construction had to be monitored, college policies had to be developed and approved by the Board, the entire educational program had to be established, which included admissions, records, financial aid, the transfer and career programs, courses, and the catalog and Fall 1970 schedule of classes had to be put together and published. While some of these things followed from Smith’s experience at Corning, and many responsibilities were delegated to the first cadre of administrators, this was still all a brand new experience for all. And, it has to be noted, not only was Smith the first president of the college, but this was also his first presidency. There was a lot of trailblazing to be done.

Not the least of Smith’s responsibilities was getting the county acquainted with the college that was to become a presence in the community within a year. This required him to meet with the county’s elected leaders, Columbia’s leaders, and any number of community, civic, social, educational, and business groups, and to give talks and presentations to these groups as well as at town meetings16 and to the county’s high schools.17 Not only that, but there were some Howard County residents who perceived the college more as a part of Columbia rather than a part of the county; so, explaining that away took some work. With all of Smith’s efforts and challenges, there was still Catonsville Community College that had been the draw for the county’s high school graduates. So, pitting a college that did not exist yet against an established one just across the county line was a formidable job of marketing and public relations.

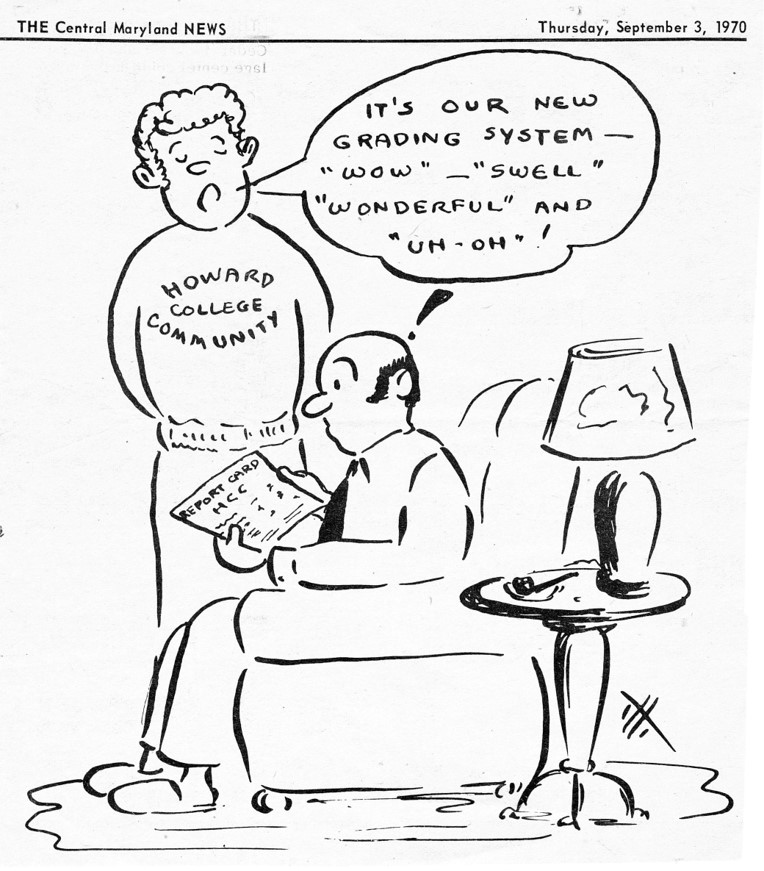

Smith was a visionary then, and he continues to be so even today. In an interview for the college’s cable TV channel in 2005 Smith reiterated his philosophy that a true learning institution focuses on the student and this requires a school to take into account a student’s rate of learning and learning style. Consequently, such things as a college’s primary teaching approach of lecture and the establishing of fixed time limits for learning (i.e., semesters, quarters, etc.) are inconsistent with a true learning environment. But even back when he was hired and his views were known to the Board that employed him, some of his vision was met with a degree of caution and resistance within the county. Smith publicly promoted the concept of non-punitive grading, especially as it was demonstrated in the college not having an ”F” grade. He did not believe that students should be institutionally penalized for academic non-performance. Frederick K. Schoenbrodt, who was the founding Chairman of the college’s Board of Trustees, approved of the grading policy, but with the admonition that standards had to be maintained. The county’s Superintendent of Schools, M. Thomas Goedeke, flat out disagreed and argued that students had to be held responsible for their performance, and that failure was part of life and part of the real world.18 Goedeke’s comment, as quoted in the newspaper, requires some thought, since a year later Wilde Lake High School opened, under the principal, Dr. Jack Jenkins, and employed many of the same educational concepts as were promoted by Smith for HCC. Wilde Lake High School had individualized and self-paced learning, and some non-punitive grading. So, Goedeke’s comments, if quoted accurately, present difficulties. In any case, the Board supported Smith’s initiatives and, for fifteen years, the college did not have an “F” grade; rather, there were two non-punitive “X” grades. In addition, there was a “D” grade the first year, but it was removed the next year. The “F” grade replaced the “X” only in 1985, and the “D” returned in 1992.

Applicants for the full-time faculty positions that would begin in the fall were interviewed early in 1970, and many of the hired candidates volunteered their time in the spring and summer to help with curriculum development, course descriptions, and helped the librarian to develop collections in their respective areas, and this was no mean feat since the development of courses, programs, and the library collection were all starting from scratch.

Fall 1970 saw the debut of the Mary Tyler Moore Show on TV and NFL Monday Night Football began. The Cleveland Browns beat the New York Jets 31 to 21. It was Richard Nixon’s second year as President, and the Orioles beat Cincinnati in the World Series, 4-1. Howard County’s County Executive was Omar Jones, who formerly had been Principal of Howard High School, and Howard Community College opened on Monday, October 12, 1970 in its just constructed one-building facility in Columbia, Maryland. HCC could claim “the distinction as the first Maryland community college to begin with its own, new campus and was the fourteenth community college in the statewide system.”19 But, the campus did not look like a college. Its massive concrete, two-storied, rectangular architecture looked more like an industrial facility than like a college. In addition, much of the land around the college had been cleared and so, the structure appeared to be in the middle of a field. Sometime during the first year Marinich recalls meeting someone who asked him where he worked. When Marinich explained the location of the college, the other party commented that he thought the building was a facility belonging to a utilities company.

The October opening of the college was late, but the state approved the opening which was supposed to have happened in early September because of construction problems and delays; although, registration was still held in August at Slayton House in the Village of Wilde Lake, Columbia. A full-time student who registered for 12 to 17 credits paid $150 tuition. In-county tuition for part-time students was $13 per credit.

There was a total of 594 students who enrolled that fall; 240 of whom were full-time students and 354 part-time. This modest enrollment is understandable. The college, being brand new and, having no track record, was not yet well known in the county. Many of the full-time staff were new to the county. Several faculty had just recently moved into the county, and three senior administrators, the President, Dean of Faculty, and Dean of Community Service, had recently relocated from community college positions in New York State. The only native Howard Countian was the Director of Administration, Darrel Campbell. In addition, Catonsville Community College, which began in 1957, was a known quantity, and was established in the area, and had drawn many Howard County graduates for a number of years since it was virtually just across the border in Baltimore County. And further, there were the other established community colleges in adjacent counties that had drawn Howard’s citizens. Frederick Community College to the west also began operations in 1957. There was Prince Georges Community College south of Howard County that started in 1958 and Anne Arundel Community College to the east that opened its doors in 1961.

The first year of operation was one of getting, and becoming, organized. Policies and procedures were not yet fully developed, and those that existed may in some cases have been copied from the by-laws and policies of other existing community colleges. If this was the case, it certainly made sense since it avoided re-inventing the wheel; however, there was some initial confusion since this first set of Board of Trustees By-Laws had entries about faculty tenure and division chairs neither of which the college had when it opened; indeed, there would never be tenure, and division chair positions would not exist until the late “70’s.

In the first set of by-laws faculty were defined as “all full-time members of the professional staff including the President, Deans, Directors, Librarians, Counselors, teaching faculty and other such persons designated by the President due to their educational duties and responsibilities.”

The 1970-1971 academic year began with 10 full-time teaching faculty, one librarian, and about 14 part-time faculty. The first full-time faculty members were:

Daniel Friedman, Chemistry and Physics

Janet Holter, Secretarial Sciences

Donna Kirkley, English and Speech

Lawrence Madaras, History and Political Science

Vladimir Marinich, Data Processing and Sociology

Robert Newkirk, Physical Education

Alan Pipkin, Biology

Bruce Reid, Electronics

Elizabeth (Betsy) Siggins, Librarian

Shirley Symonds, English

Harold Sylvester, Mathematics

Seven of the ten first full-time faculty were in their late twenties and early thirties. We know some of the backgrounds of these early faculty; Friedman had taught for four years at the Community College of Baltimore as assistant professor of chemistry, Kirkley had taught at UMBC and Prince George’s Community College, Madaras had several years teaching experience at Springhill College in Alabama and then at Coppin State, Marinich came out of the computer industry but had done part-time teaching at American University, Newkirk had been Head Lacrosse Coach at Cornell University, Pipkin came from several years at the University of Arkansas, Reid came out of the electronics and engineering industry, Sylvester had taught at Harford Community College, and Symonds was “a relative neophyte to teaching.20

An orientation program was organized by the administration in August 1970 and, because construction of the college was not yet completed, the orientation program was held in the American Cities Building. The new faculty heard presentations by the County Executive, Mr. Omar Jones, James Rouse, and other county leaders. There were also workshops on teaching techniques, Human Potential sessions, and discussions on student motivation and student characteristics. Each faculty member was given, and asked to read, the then popular book by Jerry Farber entitled, The Student As Nigger: Essays and Stories. The language of the book was often crude and vulgar, but its point was that students had been treated as second-class citizens in the past, and how that had to change. The orientation program established a positive atmosphere to the start of the year, and to the college’s beginning, and Smith’s presentation during this session was of particular importance. He presented his vision that set the tone for the future. Smith began with a history of the community college movement in the U.S., its current state at the time, Maryland’s place, and his vision for the college. Smith described the college as being a vital part of the community; one that provided academic programs and also “short courses, lectures, concerts, foreign films, performing arts groups, refresher courses, seminars, clinics, panel presentations¼”21 He continued by focusing on the student. In Smith’s words, “the college will be learner-centered and not teacher – or discipline-centered. Concern for the learner should be foremost. As a matter of fact, I think we should abandon the term “teacher,” because I believe that it has no longer any relevance to education. Instead, I believe that we should be known as ‘directors’ or ‘managers’ of learners. This puts the learner at the center of the institution.”22

Smith summarized his vision by questioning “some long-standing practices in education and some of the sacred cows.” 23 He questioned the lecture method as the primary mode of instruction, suggested that the textbook should not be the sole medium for learning, criticized the normal grading curve, and the “punitive grading practices, such as ‘D’ and ‘F’,” and emphasized the need for behavioral objectives.24

The backgrounds, experiences, and capabilities of the faculty came in handy in the first year. Several of the full-time faculty taught across disciplines; Marinich taught Data Processing and Sociology, Madaras taught American History and European History, and Kirkley taught Speech and English. And when the mathematics professor became ill and hospitalized, Friedman and Reid took over the math courses.

There were no departments or divisions. All faculty reported directly to the Dean of Faculty; not surprising since there was a total of twenty-four faculty, and just about each one was a department unto themselves and, in several cases, as already mentioned, some faculty taught across disciplines. There were no student evaluations of faculty, nor was there a formal planning and evaluation system for faculty or for administration. And everything was in one building: the classrooms, science labs, faculty offices, administrative offices, the library, bookstore, mailroom, necessary facilities, other management areas, and a cafeteria. The cafeteria was located in the southwest corner of the building. Chairs and tables were plastic, and sometimes, if someone leaned too far or rocked, the chair legs snapped off. Food and drink were out of vending machines in an adjoining room. The design of the building included a computer room with a raised floor for the many needed cables; but the college did not have a computer, so the room was used as an art studio for several years. (The reader is invited to study Appendix I for a three-dimensional rendering of the first building).

The college embarked on the systematic approach to learning in this first year. This became known as the Systems Approach. The particular approach that was taken was to have faculty develop clearly stated objectives by which student learning could be measured. The college demonstrated the commitment to this approach by employing Dr. Al P. Mizell as the instructional developer. It was his job to educate the faculty in educational theory, and to train the faculty in the development and use of behavioral objectives. Mizell worked with instructors as they developed their course and unit objectives, and he assisted the instructors to make sure that objectives were clearly, sequentially, and accurately stated, and that tests correctly matched objectives. During the year Mizell offered workshops and everyone who was responsible for developing objectives was given copies of Benjamin Bloom’s and David Krathwohl’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Each faculty member was given both volumes, Handbook I on the cognitive domain, and Handbook II on the affective domain. The development of courses using behavioral objectives was seen as being of such importance and effort that in the first two years of the college’s operation faculty carried a teaching load of 12 credits rather than the standard of 15. In addition, a number of faculty visited Brookdale Community College in New Jersey to learn of their programs that incorporated individualized instruction and self-paced learning.

GETTING INTO THE SYSTEMS APPROACH

HCC’s pedagogical approach of using behavioral objectives and non-punitive grading drew some questions and criticism. There was no “F” grade; rather there was an “X” grade to signify student non-performance, but this grade did not calculate into a student’s GPA. There were some high schools in the county that had begun to use behavioral objectives and learning activity packages and, because the college employed similar techniques this led to some perception that HCC was “a high school with ash trays.” The non-punitive grading became the subject of a cartoon in one of the local newspapers.

There were a few individuals who had reservations about the “systems approach.” Dr. James Bell, who was employed in 1971 as the full time psychology professor, thought that while the concept of behavioral objectives was pretty clear, the administration did not have a unified sense or direction about what systematic instruction meant and this, he felt, created confusion.25 Dr. Jerrold Casway, hired in 1971 as the second full-time historian, thought that the school’s focus on the development of systematic instruction was damaging in that it made educational technicians out of faculty rather than enhancing their teaching skills. Virginia Kirk, hired to teach English the same year as Bell and Casway, concluded that focusing on what students had to learn and organizing courses and units within courses in an orderly, detailed manner, and in having learning organized in terms of end results (objectives) improved both teaching and learning. The instructor became more organized and the student understood what had to be learned.26 Peggy Armitage, who joined HCC as a Counselor in 1976 had pretty much the same thoughts on the matter, as did Bruce Reid who was one of the “originals,” and so did Andrew Bulleri, who joined the college in 1971 to teach mathematics and electronics.

Bela Banathy, author of Instructional Systems, conducted a seminar at HCC that basically dealt with the second phase of the college’s systems approach. The faculty had all gone through the initial program of learning to write behavioral objectives according to the Bloom/Krathwohl model and they were using those objectives in their classes. Now it was time for the next step. Banathy saw learning within the framework of systems; and in this he was influenced by the works of Robert M. Gagne and Robert F. Mager. Banathy’s design of instructional systems consisted of a six-step process:

Formulate Objectives

Develop Criterion Tests

Analyze Learning Tasks (ALT)

Design the System

Implement and Test Output

Change to Improve

Banathy’s entire approach and philosophy focused on learning, not on instruction. The student was the center and, if learning was the true focus of an educational institution, the way in which a student learns and the pace at which a student learns becomes critical. The consequences of such an approach were far reaching since it meant that in the ideal standard classrooms, traditional lecture courses, schedules, and even semesters became either obsolete or irrelevant.

Banathy’s model became the HCC model. The steps listed above became part of faculty responsibilities in ensuring that course materials, which would be in behavioral terms, would be validated by having faculty go through a rigorous, thoughtful process. Course and unit objectives had to be developed; that was fundamental. Quizzes, tests, and examinations had to be tied directly to objectives. The next part of the process was the Analysis of Learning Tasks (this quickly became known as the ALT). Faculty had to figure out what it was that a student had to learn in order to achieve an objective. This led to the next step that Banathy called Design the System. At HCC it became known as the development of alternative learning strategies (the ALS). This was the kicker! Since this entire intellectual process revolved around the student as learner, it became clear, as many already knew, that not all students learn at the same rate or in the same way. So, faculty had to develop alternatives within their own classes, and put them into practice. This became a major chore and simply did not work in many cases due to resource availability, the amount of time that a faculty member had to develop alternative learning modes, and finally the inflexibility of the semester system that required students to begin and end on fairly precise dates. The final stage of the system was to keep track of how things worked and to make changes, as appropriate, to improve the learning process.

In addition to this system being a requirement put on faculty as part of their professional obligation, it became a major part of the promotion criteria if faculty wished to move up through the academic ranks. Thus, a key element of a faculty member’s upward mobility in rank required pedagogical knowledge leading to better and more comprehensive instructional materials and approaches. To achieve the rank of professor a faculty member had to take at least one course through the entire process which, of course, would take a number of years. Marinich recalls that on a number of occasions over the years faculty observed that the level of systems knowledge and performance that they were expected to master were equivalent to going for a Ph.D.

There was more to HCC’s commitment to students than the “systems approach,” and this had to do with what was called “humanistic” education. The faculty were introduced to this philosophy right from the start when they were encouraged to read Jerry Farber’s outrageously-titled book. More than that, Smith supported faculty to participate in Achievement Motivation seminars and even to co-lead them once they acquired the skill. Terry O’Banion who is now best known for his book A Learning College for the 21st Century and as Executive Director for the League for Innovation in the Community College was invited to come to HCC in January 1972. He conducted a seminar/workshop that was attended by faculty, counselors, and some administrative staff. It dealt with the human side of education, and a number of ideas that O’Banion shared with the staff back then, in the early 1970’s, could still be found in his more recent works. The college also developed and conducted workshops on communication, listening skills, and what became known as Level II Advising that became part of the faculty/professional development repertoire. This was in addition to those professional development activities that were about developing behavioral objectives, ALT’s and ALS’s, criterion testing, etc.

WE WERE SMALL, BUT BURGEONING

During the college’s planning and development in 1969, and during HCC’s first year of operation, Student Services was under a Director, who also handled admissions. This was Dr. Dean DesRoches. There was a Registrar with an assistant, and one counselor. The Director reported to the Dean of Faculty, and the Registrar, who at that time had the title of Recorder, while officially under the Director of Student Services, really reported to the Dean of Faculty. A Student Government Association (SGA) was formed and a faculty member, Marinich, served as advisor. One of the first student activities was a dance held in the college’s cafeteria on Friday, November 20. A local group, “Liquid Fire,” provided the music. A student newspaper, The Tabloid, also began in 1970, and it, too, had a faculty advisor. The newspaper was, indeed, in tabloid format. It was four pages long with the first page devoted to college news and the last to sports; the inside (second) page was letters to the editor and op/ed articles that often spilled over to the third page; and often enough students were critical of some college process, schedule, actions of some college official, general suspicion and occasional rejection of authority, etc. Not surprising, since the early to mid-1970’s were part of the 60’s. Or, as stated by the historian, Paul Boyer, “the sixties cast a long shadow, and the decade’s political and cultural trends did not vanish as the new decade began.”27

Community Services (later to be changed to Continuing Education) was a dean’s level position, and it was administered by Joseph DeSantis who had been hired in 1969, as had the other senior administrators. In addition to offering courses DeSantis also established an aggressive program of getting the college involved in community activities. He encouraged faculty to be involved in the community by developing a speaker’s bureau and by encouraging faculty to teach a credit-free course in whatever area was appropriate. At the very beginning Community Services, under DeSantis, scheduled credit-free courses and also scheduled evening credit courses. In fall 1970 DeSantis’ area scheduled 28 credit-free classes and 33 evening credit classes. The evening credit classes were all scheduled on campus, and all but one was two evenings a week. All the credit-free classes were scheduled at Howard High School, Mt. Hebron, the Howard Vocational Technical School, Faulkner Ridge Elementary, and Wilde Lake Middle School (Wilde Lake High School, the first high school in Columbia and the fifth in the county, did not exist yet; not until 1971). We do not know how many of any of these courses had sufficient enrollments to run. Daytime credit classes were under the Dean of Faculty. The fall 1970 schedule listed 73 day classes. The schedule was all of four typed pages, single-sided, on 8½ by 11 paper; five pages, if the cover title page was included. We also do not have data on the number of day credit courses that had sufficient enrollments to run.

The following year, 1971, was, as are all years really, eventful for the nation, for the county, and for HCC. The Pentagon Papers were published, thereby heightening the controversies over Viet Nam even more; the 26th amendment to the Constitution was passed, lowering the voting age from 21 to 18, Starbuck’s began in Seattle as a single coffee shop, and the Columbia Mall opened with two anchor stores; Woodward & Lothrop and Hochschild Kohn.

In March of 1971 the first faculty organization was established. It was named the Faculty Association and its membership was perhaps a little over thirty members. This membership included teaching faculty, both full-time and part-time, and administrators, that included the deans and the president. The first officers of the Association were Madaras as Chair, Marinich as Vice Chair, Kirkley as Secretary, and Friedman as Treasurer.28

Toward the end of the spring semester Symonds, the full-time English faculty member tendered her resignation. Marinich recalls that she was not in agreement with the innovative philosophy and practices at HCC and, therefore, felt that she should leave. Kirkley, on the other hand fully expected to continue; however, her contract was not renewed due to her “personal physical condition.” She was pregnant. On March 24, 1971, Kirkley received a letter from the Dean of Faculty in which he praised her for her contributions to the college, but said she would “not be offered a full-time professional contract for the 1971-72 school year.” His letter further stated,

I know that you will thoroughly enjoy your soon-to-be motherhood status, and most wholeheartedly encourage you to reapply at HCC when you are ready to return to teaching.

Smith concurred.29 It should be noted that this was 1971, and the Pregnancy Discrimination Act was not legislated until 1978. Several years later Kirkley returned to the college. In 2004 she retired with the rank of Professor Emeritus.

May 23, 1971 was a sunny spring day in Howard County, and ideal for the dedication ceremony that was held outside of the main entrance by the flagpoles. There probably were not many more than about 100 people in attendance, including college staff, the platform party, students, and members of the community. The major address was given by the Lieutenant Governor of Maryland, Blair Lee III. There was also the presentation of the keys. The Howard County Executive, Omar Jones, presented the keys to the campus, and Fred Carey of the Perkins & Will architectural firm presented the keys to the buildings. The keys were accepted by Frederick K. Schoenbrodt, who was the Chairman of the first Board of Trustees of the college.

That summer the college introduced the Summer Grant Program that allowed faculty to receive stipends to work on program development, course improvement, and some professional development activities, while they were off contract. Faculty had to propose a project that was clearly seen to be of value to the institution. In that first year the Dean of Faculty and the Instructional Developer reviewed the proposals and chose those that would best serve the institution. The Summer Grant Program has continued every year since then, thereby becoming institutionalized.

The second year – the 1971-1972 academic year, was probably as exciting and dramatic as was the first. In his talk with the faculty at the beginning of the first year, Smith had understood that the initial phase of the college would be an interim period during which time “the best practices will be used temporarily as guided progress is made toward the post-interim period when effective innovative practices will be a reality.”30 While his focus was on educational processes, it was clear that such practices would require an organization that could get this done and that more staff were needed as the college grew. And the college had grown; full time enrollments were 337 (up from the prior year’s 248), and part time enrollment was up from 363 in 1970 to 390.

There was a major reorganization in the student services area. The director, counselor, and registrar had left in the summer of ’71. The new organization of this area would have a Dean of Students. Dr. John Fiedler, who had gotten his Ph.D. from the University of California, was hired for this position and, given the position as dean’s level, he reported directly to Smith. Five counselors were hired, and all had administrative responsibilities in addition to their counseling duties. These were the individuals and their administrative duties:

Charles Dassance, Financial Aid

Diane Downey, Career Counseling

Frank Gornick, Admissions

Katherine Kelleher, Student Activities

Robert Levene, Veterans Affairs31

Of the people named, almost all left within a few years primarily “because the rapid growth of community colleges created enormous opportunities for experienced community college administrators.”32 Dassance and Gornick left to move on with their careers, and eventually became community college presidents and, as a matter of fact, over the years HCC produced a number of presidents. (See Appendix II). Downey left to go into the banking field as a trainer, and Kelleher subsequently married and moved away with her husband. Levene remained, became head of counseling, and then moved to faculty status. He retired in 2005 as Professor Emeritus of History at HCC.

That same year faculty ranks increased with the hiring of the following:

Martha Aldrich, Nursing

Faye Armstrong, Secretarial Science

Claire Benjamin, English

James Bell, Psychology

Andrew Bulleri, Electronics and Mathematics

Ronald Carter, English

Jerrold Casway, History

Bernadene Hallinan, Director of Nursing Education

Roslyn Judy, Art

Virginia Kirk, English

Vincent Koehler, Mathematics

James MacGregor, English

Richard Matlick, English

Ann Marie Zalewski, English

Again, there was a mix of backgrounds and experiences. Bell had previously taught at Elmira College in New York, Bulleri came from Western Illinois University with six years teaching experience, Casway had just earned his Ph.D. in History from the University of Maryland and had been a graduate teaching assistant and had taught as an adjunct faculty member. Kirk was a recent recipient of her M.A. from Michigan State University, and Matlick had a number of years experience at several community colleges.

In addition to all these faculty and counseling positions two administrative positions were created; one was Director of Funding and Development, David Tucker and the other was Assistant to the President for Public Relations, Dagmar Grimm.

Smith was also concerned about the relationships between major units of the college, constituent groups, and how policies and procedures would be integral to all of these. In July 1971 he established a task force on Internal Governance to develop a set of recommendations on the structure and governance within the college that he could review and recommend to the Board of Trustees for approval. The result was the creation of a College Council and three committees; Curriculum and Instruction, Community Services, and Administrative Services. All these bodies would have representatives of HCC’s constituent groups; administrators, faculty, staff, and students.

As in the first year the college had four transfer A. A. degrees, four career degrees, and one certificate. The transfer A.A.’s were Arts and Sciences, Business Administration, General Studies, and Teacher Education. The career A.A.’s were Accounting, Business Data Processing, Electronics, and Executive Secretarial Science. The one certificate program was Stenographic-Clerical, and this was a one-year Certificate of Proficiency.

A Nursing Program was in the planning stages, but was not yet established. To get the program under way for the following fiscal year a Director, Bernadene Hallinan, and a faculty member, Martha Aldrich were hired. Both had been at Corning Community College and had worked under Smith.

1971 was the year that the school’s official colors were established. In the few months prior to December of that year, the SGA and its faculty advisor reviewed the symbolic meanings of various colors by looking through historical and heraldic sources. Finally, a poll of 180 students was conducted via a questionnaire to determine the school colors. The selection was maroon and ivory.33 That month’s HCC newspaper, The Tabloid, was printed in red on off-white paper. This may have been in recognition of the school’s new colors, since the newspaper was generally printed using black ink.

In January 1972 the college ran its first “minimester.” This was the term used for the winter intersession period. Three classes were offered with an enrollment of 36 students.

In the early spring of 1972 a short-lived faculty evaluation process was established. It consisted of a self-evaluation by the faculty member, peer evaluations by three of four peers that the faculty member felt were “qualified to accurately evaluate his performance,” and an evaluation by the Dean of Faculty.34

THE CHANGE AGENT

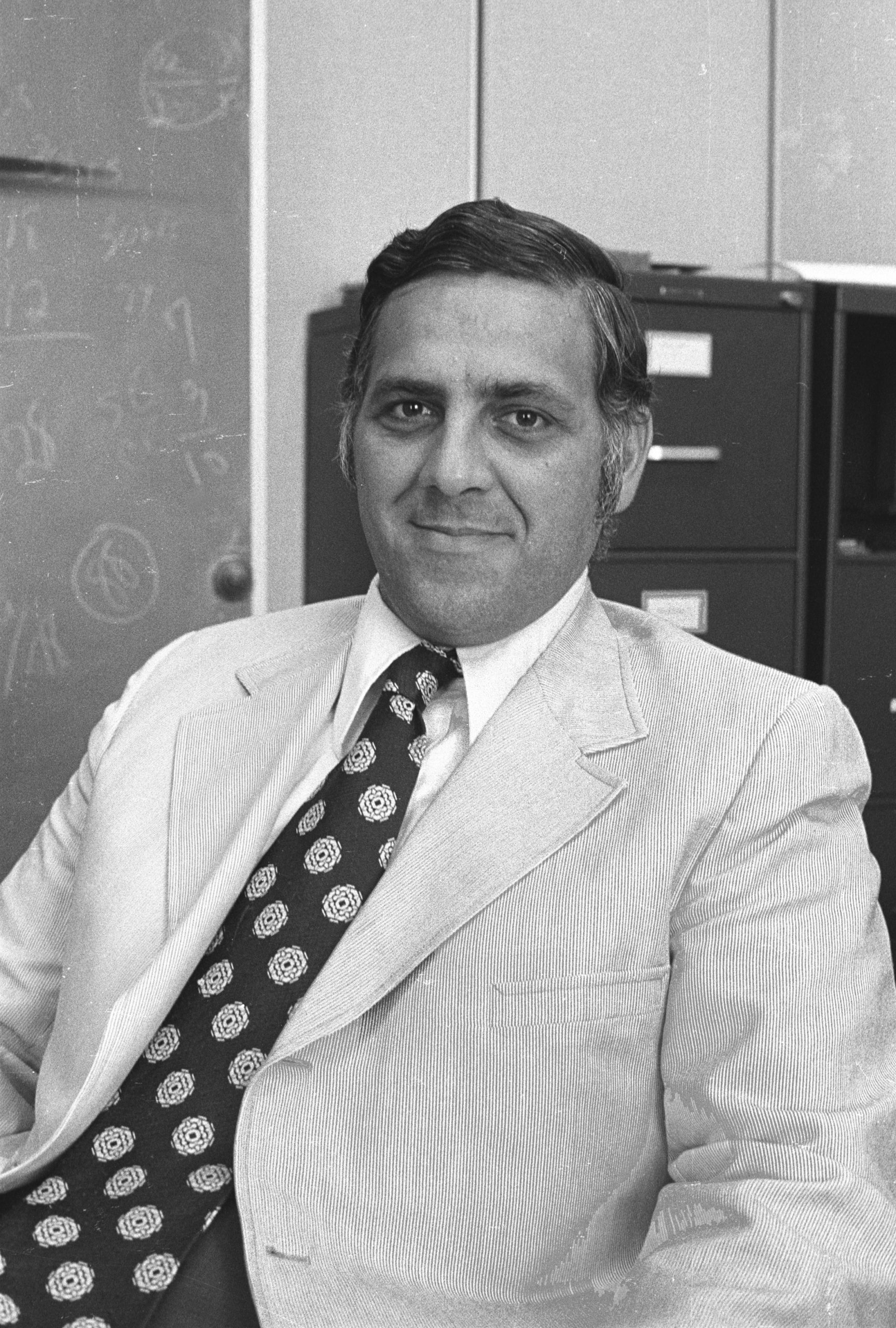

The summer prior to the start of the 1972-73 academic year was a particularly active season for the administration. Of the four senior administrators who reported to the president, three left the college; the only one remaining was Joseph DeSantis. The president upgraded the Administration Director’s position to dean’s level and he hired Richard Pettingill to be the Dean of Administration. Pettingill had been Smith’s colleague at Corning Community College. Search committees were formed to review applications, interview candidates and make recommendations to the president for the other two positions. A Dean of Instruction (this was the new title) and a Dean of Student Services were hired during the summer. The new Dean of Student Services was Dr. Robert Anderson, and the new Dean of Instruction was Dr. Donald J. Donato. The latter was a very forceful presence, and his tenure at HCC set a direction that would last for many years. Donato had earned his B.S. and M.S. from the State University of New York, and his Ph.D. in Counseling from the University of Missouri, and had most recently been employed at a Pennsylvania community college as Dean of Students and Director of Research. As the staff came to know him it became clear to many that he was on a career path to a presidency.

Donato saw himself as a change agent and, with the president’s concurrence, he began to develop a quantitative faculty evaluation system as one of his first major responsibilities. One or two faculty committees were established to come up with the foundation for a more objective faculty evaluation system. The background to this is founded in the prior year’s faculty evaluations that proved disappointing to some individual faculty members. Communication had not been clear on the nature and consequences of faculty evaluations, and the entire process, at least in the eyes of some faculty, was not organized or executed consistently and apparently with little or no faculty input in its development. The evaluations were based on a combination of self-evaluation, peer evaluation, and evaluation by the Dean of Faculty. All these elements were subjective in that only the most general guidelines were given as to how the evaluations should be conducted.

Donato was influenced by the work of Wilbert McKeachie of the University of Michigan, who is an authority in the areas of psychology, teaching at the college level, and active learning. Donato visited McKeachie to show the latter a draft of Donato’s evaluation system, and returned encouraged that McKeachie thought it had some positive attributes. Donato verbalized this to Marinich at the time.

The Faculty Evaluation System quickly became known as the FES. The first draft was developed in October 1972, and was 17 pages long. The content of these pages was a highly detailed description of faculty responsibilities in the following categories: teaching load, student advising, administrative responsibility, program/instructional development, college/community service, and personal/professional development. Each of these areas was assigned a point value and the estimated time requirement, in hours, for their accomplishment. In addition, each one of these areas was further broken down into more detail. Teaching was broken down into point values awarded for the number of preparations, student credit hours generated, and contact hours. In college service, as an example, a faculty member accrued ¼ of a point for attending “a student activity such as a dance, concert, etc.”35 A faculty member was generally supposed to accrue 71 points in a year as an average, and was to put in an estimated 1,405 hours of effort. Salary increases were based on total points accrued.

While there were areas of the system that required faculty to plan an activity, such as a pedagogical project, most of the system contained prescribed activities with little planning, in the way of forward thinking, on the part of the faculty. It may be interesting to note that the FES was reminiscent of early twentieth century industrial management, which was the era of such researchers as Frederick Taylor and the Gilbreths, and of time/motion studies that attempted to improve worker efficiency. The flaw in those systems was demonstrated in the famous Hawthorne studies of the late 1920’s and early 1930’s conducted at the Chicago GE plant where motivation was seen as a major component of worker satisfaction, rather than just remuneration for more efficient work; thus, the FES was flawed in that it was almost entirely the accumulation of points. One of the few areas where the quality of performance was assessed was in the area of the faculty member’s development of “systematic learning.” The instructional developer could evaluate a faculty member’s thoroughness in developing behavioral objectives that were in keeping with the Bloom/Krathwohl model.

A surprising and curious entry, attributed to Donato, is found in the HCC Board of Trustees Minutes for October 19, 1972.

Dr. Donato pointed out that the system involves an aggregate of points which may tend to dehumanize. However, if a professional posture is maintained by faculty, this may not be a problem.

If this entry is an accurate reflection of what was said, it is surprising that the Dean of Instruction would admit to establishing a system that “may tend to dehumanize,” and it is curious that faculty would be expected to act professionally under such a system.

In addition to developing the FES, another of Donato’s very early efforts was to develop an organizational structure within his area. In August 1972 he convened a College Workshop to discuss various issues; among them was how to organize “the Instructional Program. His words:

How should the instructional program be organized?

Should there be the conventional department or divisional configuration?

What about the House or Cluster concept?

What about an interdisciplinary or career family configuration?36

Donato also wanted to discuss how the Learning Lab (somewhat like HCC’s later Learning Center) would fit into the organizational structure that would be developed. We do not have specific information on what conclusions were reached at the end of the workshop; however, Donato developed a Cluster organizational structure. This approach was based on the work of John Holland, a professor at the Johns Hopkins University. Holland’s research into personality types and career choices was developed into his Self-Directed Search (SDS), an instrument that tested a person’s abilities and interests and, on the basis of the results of this questionnaire-type test, suggested various career and employment choices that would be in keeping with the person’s background. The SDS categorized people within a six-fold typology. There were individuals who tended to be Realistic, Investigative, Social, Conventional, Enterprising, or Artistic. Individuals could also have several of these characteristics, with two or three tending to be more dominant. This became the basis for the Cluster concept of organization of the faculty. Two clusters were created; one was the Applied Human Services/Artistic, and the other was Applied Management/Social Science. Based on Holland’s work, the various disciplines were matched to his typology. Thus, Nursing, other allied health programs, English, Art, Music, and Science all tended to be associated with Artistic, Investigative, and Enterprising characteristics. Accounting, Business, Data Processing, Secretarial Science, and Social Science were identified with Social, Realistic, and Conventional characteristics. But, there were a few areas that did not fit neatly into these two categories; at least, not organizationally. Developmental courses were put under the Coordinator of the Learning Lab, and the two fulltime math faculty were divided; one was assigned to “Cluster 1,” and the other to “Cluster 2.”

While much of this was going on, the college’s life continued to be vital and exciting. Work on preparing for accreditation began in 1972 with the development and collection of general information about the college, listing and describing programs, student demographics, college bylaws and policies, procedures, long-term goals, and any other data that would be needed for accreditation. In addition, other colleges were contacted to see how they handled their accreditations, and the Middle States Association was contacted to send the college all necessary information on their accrediting policies and procedures.

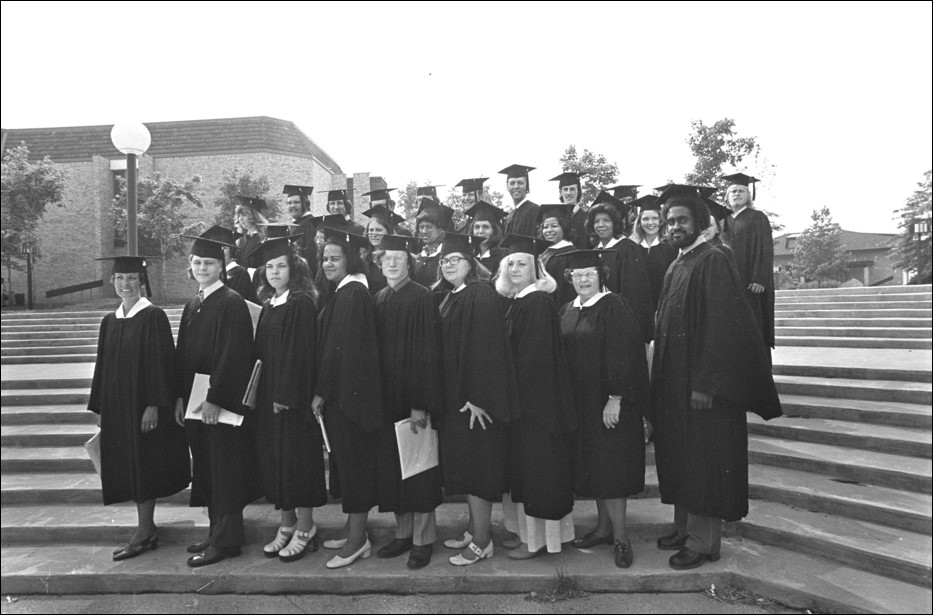

HCC’s first commencement was held on Sunday, June 4, 1972 at 2:30 P.M. at the Wilde Lake Interfaith Center. The week prior to the commencement the entire faculty met to approve the list of candidates for graduation. This was more than a formality, since the Registrar had to inform the faculty of any potential problems that a student might have in graduating, or a request that a student be allowed to walk across the stage in anticipation of completing his/her credits by summer. This practice continued for several years. Again, the college did not yet have a facility that was big enough to have a graduation ceremony, or any other large convocation for that matter. Indeed, the single largest room at the college was a tiered lecture room that could hold 72 students. There were 36 graduates at that first commencement; 35 received their Associate in Arts degrees and one received her Certificate in the Stenographic/Typing program. Terry Sanford, the President of Duke University, and former Governor of North Carolina, was the main speaker at the graduation. He was also a candidate for the 1972 Democratic nomination for President of the United States; however, Senator George McGovern of South Dakota got the nomination and in November lost the election to the incumbent, President Richard Nixon.

HCC’s sports program began in earnest in fall 1972 with the formation of a college basketball team. Its season was from December 1972 through February 1973. In its first home game HCC defeated Cecil Community College 115-60. The home games, by the way, were played at Wilde Lake High School, since the HCC gym did not exist yet.

HCC’s first international trip was planned during the Fall 1972 semester, and in January 1973 approximately 22 individuals went to the Soviet Union for two weeks. The group consisted mostly of community residents, but there were four HCC students and one math faculty member who were part of the group. The trip was led by an HCC faculty member, Marinich, and the group visited Moscow and Leningrad and, in addition to the historic sites in each of these cities, saw an opera at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, attended a performance of the Kirov Ballet in Leningrad, and met with young Soviet students at a local school and at a youth center (known as the “Pioneer Palace”). The entire trip cost a participant $495.

The fall 1972 semester also saw its share of student involvement. The Student Government was particularly active in promoting various student social events, dances, occasional guest lectures, and also in being the voice for students in general. The student newspaper continued into its third year of operation and also acted as the voice of the students. Some of The Tabloid staff saw themselves in a new light. In a short informal conversation that Smith had with Marinich at the time, Smith mentioned that a student had contacted Smith’s office to set up an interview with him. When asked what the purpose of the requested meeting was, the student answered that she was an investigative reporter for The Tabloid and told the president’s secretary that investigative reporters should have free access to the president. Marinich recalls that Smith was amused.

Around November 1972 there was quite a bit of student discontent that surfaced. The issue was the class schedule for the spring 1973 semester. Students complained and got a meeting with the Dean of Student Services, Dr. Robert Anderson. The meeting was held in the cafeteria and about 100 students attended. Several faculty members were there, as well as a representative of the local newspaper, the Columbia Flier (which at that time was printed on 8 x 11 paper). The major complaint was that the number of courses and sections scheduled for the spring was very limited; some courses had only one section. One student noted “that many of the second year level courses had only one section making it difficult for working students, housewives and returning veterans to make out their programs without a time conflict.”37 From the college’s perspective, the issue was one of cost effectiveness; it was better to have fewer courses with larger enrollments than more courses with smaller enrollments and the possibility of having to cancel low enrolled classes. The students at the meeting preferred the second alternative. The following week the college added three courses and an additional section of another course in an attempt at compromise. Students were generally still not satisfied and there was an attempted boycott of spring registration. There was a low student turnout for the boycott and the matter “fizzled.”38

PROGRAMS, NATURE WALKS, AND GROWTH

1973 was dramatic in many ways throughout the world. It was the year of the signing of the peace treaty between the U. S. and North Viet Nam in Paris. We also saw petroleum prices double; Spiro Agnew, the Vice President, resigned, the trial of the Watergate burglars began, and the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade.

At HCC there were a number of continuing major activities. Beginning in January 1973, “more than 250 military veterans (had) been discharged from active duty and (had) returned to the Howard County metropolitan area.” 39 The college introduced “Project Outreach” which promoted educational benefits to the veterans. The college hired Stephen Turner, himself a vet and HCC graduate to coordinate the program. By spring of that year there was also a major reorganization planned for the following academic year. The Dean of Students had resigned and the Student Services area was put under the Dean of Instruction and a new position, Associate Dean for Student Services, was created; so, to a certain extent this structure was similar to the first year’s. This Associate Dean was responsible for Admissions, Records, Financial Aid, Athletics, and Institutional Activities/Evening coverage. Counselors, however, were now assigned to the Clusters and Learning Lab and, therefore, they reported to the heads of those areas. The individual hired for the Associate Dean’s position was William Snider. He came from the Pennsylvania community college system and had been acquainted with Donato.

Another Associate Dean’s position was created to be responsible for “career education.” This office was responsible for developing career programs; surveying employer needs, student interests, needed resources for the creation of new programs, and putting together the curricula with the help of appropriate faculty and cluster chairs. Dr. Arnold Maner was hired in this position. He had prior vocational education experience and had recently earned his Ph.D. from Texas A & M. Maner left after two years to write a proposal for a community college for the eastern shore, and subsequently became the first president of Wor-Wic Community College.

In the Administrative Services area, the Dean of Administrative Services centralized all word processing. This meant that all requests from faculty or administrative personnel were handled by a single centralized group of word processing employees. In 1973 there was a supervisor and three operators. To make operations more efficient a system was put in that allowed faculty and other staff to call the Word Processing Center via telephone and dictate letters, memos, or whatever, into dictating machines which would then be transcribed. It did not work well at all and was terminated within a few years.

New programs were added in 1973: Bio-Medical Engineering Technology (both A.A. and certificate), making HCC the first school in Maryland and one of the few on the East Coast to offer such a program; the other new program was a certificate program in Retailing. So, the college catalog that started with ten programs in 1970, and continued that way for the next two years, now had thirteen. Or, fourteen, if one counted two pages dedicated to the Arts and Sciences A.A.; there was now the Liberal Arts Emphasis, and the Science Emphasis.

HCC’s first literary journal, Sprouts, was published in spring 1973. It was 48 pages in length and had student poems and essays. This journal would continue over the years, but would change names several times; after Sprouts the names, in sequence, would be Echoes, Tomorrow’s Voices, Iron Horse Express, Ink on Paper, and now it is The Muse.

Sue Bard and Roland “Chip” Chapdelaine of the science faculty had worked on the creation of a Nature Trail on the grounds of the college, and in the late summer it became a reality. This “Woodland Walk” was created and designed to be available to the community as a natural plant and wildlife habitat. Bard and Chapdelaine produced a guide booklet and Bard produced an audio recording narrated by “Scampy the Squirrel.” Scampy became quite a draw for community residents and youngsters visiting the nature trail.

ACCREDITATION

While a lot of data gathering on how accreditation worked had been going on for quite a while, the process really went into full swing in October, 1973 with Donato’s call for a nominating committee to select an accreditation steering committee. This would be the group that would oversee the entire process. By January 1974 a steering committee was in operation and a thorough plan was formed for accomplishing the accreditation process. Functional committees were established to look at various elements of the college. The functional committees were:

Administrative Organization Committee 8 representatives

Academic Program Committee 10

Student Committee 10

Faculty Committee 7

Learning Committee 9

Instructional Resources Committee 7

Finance and Facilities Committee 8

Lay Advisory Committee 6

Each committee had student, faculty, and administrative representation, except for the Lay Advisory Committee whose role was different from that of the other committees. Depending on the particular committee the constituent representation would vary; so, the Student Committee had five students of the ten members on that committee; the Faculty Committee had five faculty of the seven members on that committee. A Board of Trustees member, Dr. Charles Leonard, was on the Administrative Committee.

The Steering Committee membership included

Donald J. Donato, Dean of Instruction, Chair

James E. Bell, Faculty, Vice-Chair

Andrew A. Bulleri, Faculty

Theron Jackson, Student

Susan Potts, Administrator

Ann Marie Zalewski, Faculty

Virginia Kirk, Faculty, Writer

Each member of the Steering Committee was also a liaison to one of the seven functional committees thereby ensuring the best communication between the committees. Not only did the liaison person report back to the Steering Committee, but chairs and representatives would also meet and report to the Steering Committee.

The Lay Advisory Committee’s role was described thus:

The following individuals were asked by the College to serve as a community advisory panel in conjunction with Howard Community College’s accreditation process. Their tasks were to react to the Self-Evaluation Document and to provide the College with some community perceptions of the College’s development.

Norman G. Bitterman, Awalt and Clark Realtors

Jean Carter, Columnist, Columbia-Howard County Times

Edward L, Cochran, Howard County Council

Howard G. Crist, Jr., President, Farm and Home Service, Inc.

Anita Iribe, Owner, Page 1 Book Shop

David Tucker, Director of Performing Arts, Columbia Association 40

The accreditation process was very time consuming and a major effort on everyone’s part, especially between January and July 1974. While there had been a problem back in October 1973, with some faculty concerns that the process might not be as open as was thought 41, the emerging process of committees and representations did allow for an open and transparent process that included students, faculty, administrators, a member of the Board of Trustees, and community persons. And, faculty chaired four of the seven functional committees and were represented by four of the seven members of the Steering Committee.

The result of all this work was the Self Evaluation Report for the Middle States Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools in July 1974. The report was 246 pages long, including introduction, a five-page table of contents, appendices, and 188 pages of narrative.

Professor Virginia Kirk, who was the official editor for the development of the Self-Study Report recently reflected back to that time and said that very few of the people involved in the process, as almost everyone was, had ever been involved in accreditation. She said that people were not quite sure what they were doing, but they certainly worked very hard. 42

The publication of the Self-Study Report was not the end of all this hard work. The college now had to get ready for the visit of the accreditation team, which was scheduled for late October. And, the Nursing Program was scheduled for its own visit from a nursing accreditation team at the same time.

By December the college was well on its way to receiving accreditation. The visits went well and the report of the Middle States Association was very positive; although a few points were made as recommendations. One comment was that the role of the counselors needed to be better defined. This was certainly understandable since in the prior four years counseling, and the entire student services area, had been reorganized in major ways four times. The visiting team also stated that among some problems “the most notable of these are the concerns over the evaluation system and the confusion about the true values and successes of systems learning.” 43 The Nursing Program had also gone through a self-study and was also accredited, and in January, 1975 President Smith received a letter from the National League for Nursing that the League had granted the HCC Nursing Program accreditation “with no progress reports requested by the League.” 44 This was high praise and virtually unconditional accreditation.

THE COLLEGE AND THE EVALUATION SYSTEM GROW

By 1974 there were 1,459 credit students; 429 full-time and 1,030 part-time. The enrollments had grown by almost 10% over the prior year. By November the Faculty Evaluation System (FES) was in its sixth revision and was 80 pages long, from an original 17 pages in 1972, as already mentioned. In that month there were 20 pages of corrections, modifications, and clarifications that were generated to the FES. The FES had become a major presence and an overwhelming preoccupation at the college. Not only were faculty, for the most part anywhere from concerned to unhappy with the system, but administrators of other functional areas had to provide information to the instructional area about their needs for faculty involvement, how many hours this involvement would require, and how many points would be awarded. Everyone involved had to focus on the most minute details, and details there were. There was concern over the number of things that people had to do and the amount of time to do them. Donato addressed one of these issues from a contractual perspective. He provided a lengthy analysis of faculty requirements. An example of the detail in his own words:

If we use a 43 week base from August 25 to June 25, subtract three weeks of vacation-like benefit (June 7 – 25) and 8 days of paid holidays, we arrive at a 38.5 week basis. Dividing the above time parameters by 38.5 results in a work week of 39/41 hours per week. Adding the 25 hours of personal time would result in a 41.5 to 43.5 hour week for Level 3 expectation.45

The concern and focus on hours and points became counterproductive simply because the system was based on time spent on activities with little thought being given to planning, quality of performance, or individual initiative. The FES was overdeveloped. Shortly things would change for the entire college.