Reform and Revolution

Claire Adams

Key Concepts

Reform and revolution have been part of our world since the beginning of civilization. This chapter examines the origins and impact of significant reform and revolution moments from the 20th century. The goal of this chapter is to investigate patterns that emerge from differing conflicts, without judging if a movement is right, wrong, or legitimate. The examples were selected to help illustrate the origins of reform and revolution. By considering the past, we might also be able to think forward into what the future holds for humanity.

Change Is the Imperative of Reform & Revolution

Put simply, reform and revolution are actions people undertake to change an existing institution, system, or practice—with the goal of improving it. Reform involves making internal changes or modifications and without completely removing the existing system. For example, American civil rights movements (note the plural usage) that began in the mid-1950s resulted in the reform of laws and policies covering civil rights, voting, and labor. These changes strengthened long-denied human rights protections and delivered them to people of color, women, and migrant workers. The reforms did not drastically change the country’s political structure. At the same time, they ensured fair and equal treatment for all citizens regardless of race, creed, gender, class, ability, sexuality, and ethnicity.

Questions for Critical & Creative Thinking

- Do you believe reform achieves equality, liberty, opportunity, and human dignity for all people? Or is revolution necessary to enact change?

When Reform Becomes Revolution

When changes are not being implemented or have not gone far enough, reform may become the catalyst for revolution. The goal of revolution is usually an extreme or complete change to the status quo, including the replacement of the existing authority.

The definition of revolution includes two aspects:

- A forced replacement of a government or social institution to establish a new system

- Multiple events orbiting around and driven by the perceived need to initiate progress

Why We Fight: Examining Historical Events

The following examples present several 20th-century reform and revolution events. We will examine causes, key developments, and the consequences of war, as well as reconciliation efforts and political initiatives. These artifacts are presented from the perspective of participants, combatants, and civilians, as well as news, art, and literature.

Alexander Hamilton wrote in The Federalist papers:

“To judge from the history of mankind, we shall be compelled to conclude that the fiery and destructive passions of war reign in the human breast with much more powerful sway than the mild and beneficent sentiments of peace; and that to model our political systems upon speculations of lasting tranquility, is to calculate on the weaker springs of the human character.”

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- Do you think Hamilton’s statement is correct? Or is war an inevitable aspect of life?

- Digging deeper, what reasons would be compelling enough for people to protest or to take up arms rebel against the status quo?

- Do you believe the primary motivation for going to war is the fear of kill or be killed? Or is the reason more complex? What compels countries to spend vast sums of money on troops, weapons, and warfare?

- As we have considered why we fight and how we process those experiences as human beings, have your views on war changed? Do you think it is always justified?

Whose Story Is It?

One thing often overlooked is whose stories get erased as history is documented and told. To critically analyze an artifact of reform or revolution, we must examine the unofficial, as well as official versions. We must often address contradictory messages about why we fight. For example, are we waging war to defeat political oppression? Or is there another agent driving the conflict, such as religious ideology or financial gain? Keep these various perspectives and challenging questions in mind as we examine reform and revolution artifacts from the 20th century.

Credit: Eric Durr.

New York National Guard. Public Domain. https://www.nationalguard.mil/Resources/Image-Gallery/News-Images/igphoto/2002042273/.

The Harlem Hellfighters by Max Brooks is a graphic novel about the 369th Infantry Regiment. This all-black American infantry unit fought during WWI. The homecoming parade honoring the decorated war heroes turns somber when they learn of the notorious race riots of the Red Summer of 1919. The final panel’s caption reads:

“It’d be a nice story if I could say that our parade or even our victories changed the world overnight, but truth’s got an ugly way of killin’ nice stories. The truth is that we came home to ignorance, bitterness, and somethin’ called the ‘The Red Summer of 1919,’ some of the worst racial violence America’s ever seen. The truth is that our fight, and the fight of those who looked up to us as heroes, didn’t end with the ‘the war to end all wars.’”

Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence is a textual artifact that marks the birth of the United States. It also defines universal rights guaranteed to all people, not just its citizens. The document was adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, as part of the announcement that the 13 American colonies were no longer members of the British Empire. 56 representatives of the 13 newly independent sovereign states signed the declaration.

This document defines the American view of freedom and revolution, underscoring particular cultural perspectives. The historical context plays a key and disconcerting role. Slave labor was central to the flourishing of the American economy. Nevertheless, the declaration states that all men are created equal. This equality did not exist for the slaves, who earned no wages and were treated as property to be sold, branded, and traded. For voting and taxation, they counted as only three-fifths of a person. Interestingly, the original draft alluded to the immorality of slavery. However, this mention was removed for political expediency.

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- How does the Declaration of Independence shape the definition of freedom? How does the contradiction of slavery affect this definition?

- Do you think the declaration justifies the 13 colonies going to war against Great Britain? What other contextual factors might be involved?

- The declaration is explicit in defining rights for men. Why do you suppose it omits women, LGBTQ, or non-binary? Why do you think it makes no mention of a man’s race?

Art as a Medium of Reform

Art’s potential to inspire social and political change lies with its ability to communicate people’s innermost thoughts and feelings. Whether via poetry or storytelling, through a visual or audio medium, art can provide a comfortable way to engage in an uncomfortable conversation.

Bearing Witness through Art

The artists, musicians, authors, poets, and filmmakers featured in this section have created works that serve purposes beyond artistic creation. These art artifacts also provide moral accountability and historical documentation. This two-fold function empowers art with the role of bearing witness to reform, revolution, civil rights, genocide, war, ethnic cleansing, oppression, conflict, social justice, prejudice, and the myriad of other human experiences.

In an interview on Radio West, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Thanh Nguyen spoke frankly about the Vietnam War from the perspective of a refugee. He discussed how American filmmakers and the government represented Vietnam during the war and how they regarded Vietnamese refugees—if they regarded them at all.

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- Why were Vietnam and its people represented as mere props in a kind of proxy war with the Soviet Union? Can you think of another historical example of an artifact bearing witness to the human side of war and its aftermath?

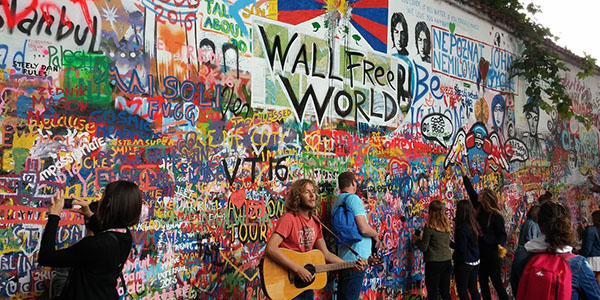

- How were street art, poetry, social media, and filmmaking used to organize what came to be known as the Arab Spring movement that occurred in parts of Africa and the Middle East?

- Can you come up with artwork artifacts associated with the Hong Kong protests that began in Spring 2019? (Hint: Start with this ArtnetNews story.)

The Harlem Renaissance

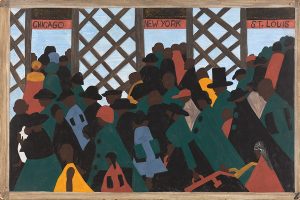

The Harlem Renaissance was a social, artistic, political, and cultural movement that began near the end of WWI and lasted into the 1930s. Harlem, New York, was a magnet for black writers, painters, musicians, photographers, poets, and scholars. Many of these artists arrived as part of the Great Migration—a mass exodus of blacks fleeing the South and its systemic racial discrimination.

Credit: Jacob Lawrence. The Phillips Collection. Fair Use of copyrighted material. https://lawrencemigration.phillipscollection.org/the-migration-series/panels/1/during-world-war-i-there-was-a-great-migration-north-by-southern-african-americans.

Millions of black citizens left rural southern states for urban centers in the northern and western states. In 1940, Harlem artist Jacob Lawrence created a 60-panel painting series called The Migration Series to bear witness to the experiences of these relocated black Americans.

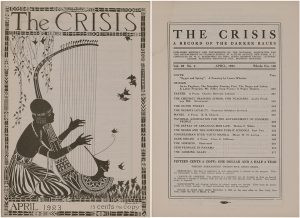

The Harlem Renaissance gave black thinkers the freedom, inspiration, and community support to explore and share their creative passions. W.E.B. Du Bois was editor of The Crisis, the official journal of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The magazine published many poems, stories, and visual works by Harlem artists. Some notable names from this period include Langston Hughes (poet), Countee Cullen (poet), Arna Bontemps (writer), Zora Neale Hurston (writer), Jean Toomer (writer), Walter White (civil-rights activist), Claude McKay (writer), and James Weldon Johnson (writer).

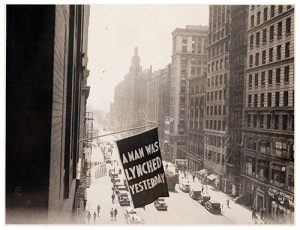

Credit: NAACP. Library of Congress. Public Domain. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/naacp/the-new-negro-movement.html#obj8.

Context is critical for understanding how important it was for black Americans to have a thriving, unfettered, cultural community like Harlem. The renaissance was much more than a source for new literature and art. The movement cultivated racial pride, social progress, and political activism in parallel with the NAACP’s New Negro campaign to lobby for a federal law against lynching. Radical musical stylings in jazz and blues attracted trend-seeking white customers to nightspots like the Cotton Club, where interracial couples danced. Nightclubs gave blacks and whites the chance to mingle socially, unjudged, which may have helped relax traditional racial attitudes among younger generations of white Americans.

War and Poetry

Poetry and art are useful media for processing human experiences, as well as broadcasting these experiences across social boundaries. British poet Wilfred Owen wrote many war poems over the course of WWI, providing an artifacts timetable that tracked his changing opinions. One of his best-known works, Dulce et Decorum Est (It Is Sweet and Fitting to Die), describes the horrors of men in trenches being assaulted with chlorine gas. Owen concludes the poem with the following line, “The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori.” The Latin phrase is an inspirational quote from the Roman poet Horace. In the face of grim reality, Owen rejects this patriotic slogan.

Credit: Suheir Hammad. “Poems of war, peace, women, power.” TEDWomen 2010. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International. https://www.ted.com/talks/suheir_hammad_poems_of_war_peace_women_power.

Palestinian-American poet Suheir Hammad is well known for her political poems about war. In “Break Clustered” (time marker 02:38), she concludes, “Do not fear what has blown up. If you must, fear the unexploded.”

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- How do Hammad’s imagery, tone, and use of point of view to bear vicarious witness to the violence of war and the experiences of women in war? How would you interpret the meaning of the poem’s title?

- What would it be like to fight for freedom abroad while your loved ones are being oppressed at home? What does it mean to fight a war abroad and at home?

War and Music

Music can profoundly affect the war effort, whether in support of or as a rejection. During WWI, the United States military assigned song leaders to training camps as a means of fostering healthy activities. Soldiers also adopted singing as a coping mechanism, making it part of the trench culture and giving WWI the nickname the Singing War. The most famous incident involving singing soldiers is known as the Christmas Truce (1914). On Christmas Eve, homesick soldiers from Britain, Belgium, France, and Germany began singing carols in their trenches. The singing led to holiday greetings and signs promising not to shoot. On Christmas Day, allies and enemies emerged from their trenches and exchanged gifts.

During WWII, performers frequently visited war camps and provided live entertainment to boost troop morale. British singer Dame Vera Lynn, the Forces’ Sweetheart,” became famous for her pro-troops support. She wrote music supporting the war effort and traveled abroad to sing for allied troops. One of her best-known songs, “We’ll Meet Again (1939),” promises a reunion for troops stationed across Europe. The chorus of the song says:

We’ll meet again

Don’t know where

Don’t know when

But I know we’ll meet again some sunny day

Keep smiling through

Just like you always do

‘Till the blue skies drive the dark clouds far away

In more recent times, Toby Keith stands out for visiting troops and supporting the war effort. In December 2001, the United States invaded Afghanistan in response to the September 11 attacks in New York and Washington, DC. Six months later, May 2002, Toby Keith released the single Courtesy of the Red, White & Blue (The Angry American).” Widely popular with troops and civilians, Keith’s song celebrates the legacy of America’s armed defense of liberty and justice. The lyrics reference his father’s military service and makes the following promise to the enemies of America:

Justice will be served and the battle will rage

This big dog will fight when you rattle his cage

And you’ll be sorry that you messed with

The U.S. of A.

‘Cause we’ll put a boot in your ass

It’s the American way

Questions for Critical & Creative Thinking

In addition to reading the lyrics, listen to the music that accompanies these two songs.

- How would you describe the mood or emotion expressed in “We’ll Meet Again?” In “Courtesy of the Red, White & Blue (The Angry American)?”

- Can you find some historical, social, political, or personal context that helps explain the widely divergent messages in these two musical artifacts?

Reform through Civic Action

The First Amendment of the United States Constitution guarantees citizens freedom of assembly (protest), petition, speech, and the press. This promise safeguards people who disagree with government policies against retribution or punishment, facilitating political and social reform through non-violent means. These civic actions can take many forms: sit-ins, flashmobs, boycotts, prayer vigils, marches, public demonstrations, hunger strikes.

The Black Lives Matter movement began in protest of George Zimmerman being acquitted of murder in the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012. Fast forward to May 25, 2020, when George Floyd’s death while in police custody was captured by the cell phones of onlookers. The video footage went viral, and the Black Lives Matter movement erupted into a tidal wave of social media protests and in-person demonstrations across the United States.

Other examples of citizens exercising their First Amendment rights include the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (August 28, 1963), Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam (October 15, 1969), Million Woman March (October 25, 1997), People’s Climate March (September 21, 2014), and most recently, Black Lives Matter (June 6, 2020).

First Amendment protections also mean that a single person can elicit change through non-violent protest. During a preseason game of the National Football League (NFL) in 2016, quarterback Colin Kaepernick demonstrated against police brutality and racial inequality by remaining seated during the National Anthem. Initially, Kaepernick carried out his public protest alone. By season’s end, he had been criticized by the president, joined by hundreds of his football peers, and become the topic of national debates. Fans indicated their support by buying his jersey—sales skyrocketed. One might even argue that the surge of support for Black Lives Matter in 2020 had been primed four years earlier by Kaepernick’s silent, personal protest.

That is not to say Kaepernick did not suffer for his civic actions. At the end of the season, the team released him. Other team owners, afraid the publicity backlash would damage profits, made no offers to sign him. He has not played in a professional game since. Private organizations are not required to protect free speech. Team owners can force players to comply with policies that establish their own (self-serving?) expectations of appropriate conduct.

Another example of one person being a lightning rod for change comes from Sudan, Africa. In April 2019, a young woman named Alaa Salah led protests calling for the removal of President Omar al-Bashir. The movement eventually sparked an armed revolution that ousted Bashir by force. What makes this civic action particularly significant is that Salah lives in a predominantly Muslim country where women are expected to be subservient to men. Furthermore, she publicly spoke out against a government with a long history of violent suppression.

In other parts of the world where these freedoms are not guaranteed, anti-government protests can be deadly for the participants. This iconic picture of a man standing in the path of oncoming tanks documented citizen demonstrations in China. The pro-democracy protesters, mostly students, marched through Beijing to Tiananmen Square in response to the recent death of Yaobang Hu. Hu worked with the CCP to introduce democratic reform before being forced to resign as General Secretary. Over several weeks, tens of thousands of people joined the students in Tiananmen Square in calling for democracy, free speech, and a free press in China. On June 3 (or 4), 1989, the government sent tanks, artillery, and soldiers to Tiananmen Square. The army killed perhaps thousands of demonstrators in what became known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre (June 3-4, 1989).

The Arab Spring (2011) was a series of anti-government protests that took place in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Yemen, Syria, and Bahrain. Street demonstrations took place in Morocco, Iraq, Algeria, Iranian Khuzestan Province, Lebanon, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman, and Sudan. Social media, especially Facebook, was instrumental in coordinating these gatherings. In Syria, the government responded to the pro-democracy demonstrations by sending tanks, heavy weapons, and troops to slaughter villagers across the country.

Questions for Critical and Creative Thinking

- How many types of non-violent protest can you come up with? Check your list against this one provided by The King Center.

Bearing Witness through Storytelling

Bearing witness is a civic action that involves observing events without intervening and changing their outcome. On-the-scene news stories and documentary films are examples of bearing witness. As mentioned previously, paintings, poetry, music, and other art forms can also bear witness. What all of these have in common is that they use storytelling to effect reform and change indirectly. Storytelling can be a powerful motivator for interventionist actions such as civil disobedience, live demonstrations, and armed uprisings.

James Orbinski is a physician, former director of the humanitarian group Doctors Without Borders, and winner of the 1999 Noble Peace prize. In his book, An Imperfect Offering, Orbinski asks, “How am I to be, how are we to be in relation to the suffering of others?” He asks this question after decades of bearing witness to famine, disease, war, and genocide. Orbinski sees his role in eliciting change as being a witness to people who are suffering, refusing to remain silent, and sharing their stories.

Observing without getting involved can present particularly difficult ethical challenges. American news photographer Malcolm Browne captured the self-immolation of a Buddhist monk during the Vietnam War on film. The monk, Thích Quảng Đức, set himself on fire to protest the persecution of the South Vietnamese government’s persecution of Buddhists. Browne was the only photographer present and shot ten rolls of film. Years later, Browne wondered if his presence contributed to the monk’s suicide; that if he had not been there to bear witness:

“[The monk] probably would not have done what he did—nor would the monks in general have done what they did—if they had not been assured of the presence of a newsman who could convey the images and experience to the outer world. Because that was the whole point ole point — to produce theater of the horrible so striking that the reasons for the demonstrations would become apparent to everyone. And, of course, they did. The following day, President Kennedy had the photograph on his desk, and he called in Henry Cabot Lodge, who was about to leave for Saigon as U.S. ambassador, and told him, in effect, ‘This sort of thing has got to stop.’ And that was the beginning of the end of American support for the Ngo Dinh Diem regime.”

Modern technology—such as television, broadband internet, social media platforms, and cell phones—makes it possible for virtually anyone, to bear witness to any event, happening anywhere in the world. Whereas previously, we may have only had access to verbal or written accounts; now, we can see events unfold in real-time.

Questions for Creative & Critical Thinking

- Consider the responsibility of bearing witness to a reform or revolution event. Does the witness have a responsibility to intervene if it means saving a life or preventing a disaster? What if they are a journalist? What if they are a doctor?

- Do you think non-interventionist storytelling can be as effective in creating change as an armed uprising or military action? For war?

The past is rich with examples of how art has shaped our sense of humanity as well as how the state of humanity has inspired art. As we think about the future, what influences do you see now that will have profound impact on the future state of humanity and the art associated with it?

Modified from Claire Adams’ open-access pressbook: From Human Being to Human Doing