The Jewish Bride (c1666)

Love is patient, love is kind: this is the visual embodiment of those great verses from Corinthians so often read at weddings. Rembrandt’s masterpiece is loving in its every brushstroke. About his young couple we know very little – who they were, whether she was a bride, whether they were actually Jewish – but this image goes beyond portraiture in any case. Their faces are radiant with adoration. Their gestures are beautiful: his hand gently placed on her breast, hers tenderly covering it. They are themselves on that day, and yet universal. The painting is a kind of secular altarpiece, an inspiration to patience, humility and love.

2 | Rubens

The Honeysuckle Bower (c1609)

Just back from honeymoon, Rubens sits hand-in-hand with his new young wife, Isabella Brant, among the honeysuckle blossom. She smiles her famously sweet smile; he leans back, legs crossed and relaxed. Everything in the garden is flourishing; and these two are secure in each other’s love. It is well known that they were perfectly matched (Rubens, a gifted writer, left eloquent letters praising Isabella’s serene good humour). Where so many 17th-century marriage portraits were rigidly formal, the historic record of a contract, this one is fluent, conversational and sensuous. The lovers incline together in all respects.

3 | Watteau

The Surprise (c1718)

In a glade, as the sun fades, with the promise of night to come, a musician sits strumming only inches away from a young couple locked in a passionate clinch. They are so rapt in their diagonal embrace – whose limbs are whose in this shudder of red and white satin? – they scarcely seem aware of this uncomfortably close spectator. Perhaps music is the food of love for them, or perhaps they are so hungry for each other they don’t hear him at all. The musician seems to show us what he (and perhaps the viewer) lacks. He’s one of Watteau’s semi-tragic observers.

4 | Renoir

Dance in the Country (1883)

Renoir’s lovers are swept away by music, dance and summer’s heat – and by each other. Their al fresco meal has been abandoned in disarray; a hat (his?) has tumbled to the ground; and she’s only just managing to keep hold of her fan as he grasps her by the wrist and waist. The whole painting seems to sway. And the crowning glory of this beautifully soft and sultry composition, with the hint of feather beds to come, is the smile on the girl’s lovely face. Candidly directed straight towards the viewer, it says that she couldn’t be happier.

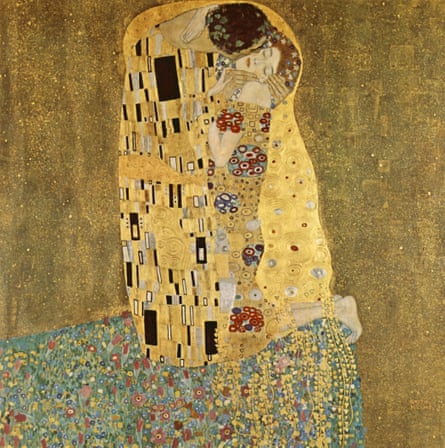

5 | Klimt

The Kiss (1908)

Wrapped up in each other, the lovers are enfolded in their everlasting kiss. Their love is out of this world (the only location is this ethereal meadow of rich cloth and jewel-bright paint) and even a little celestial: their heads are haloed in gold leaf. There’s no sense of bodies beneath all this opulence, except for her elegant toes. Bare feet, flowers in their hair: no wonder hippies loved Klimt’s masterpiece and it remains the most famous kiss in painting. A perfect square of a canvas, a perfect fit of a couple: it is just what young lovers often feel, dovetailed together in their kiss as the world dissolves into a shimmer around them.

6 | Chagall

The Birthday (1915)

Love lifts them up so their feet scarcely touch the ground. Sweeping down like a comet, or an angel, he bends over backwards to kiss her. Chagall will soon be married to the teenage Bella, his beloved muse, and so the gravity-defying strength of their partnership begins. This is a vision of wild and sensual love, but also of transcendent adoration. The shawl-draped room is a kind of shrine. Chagall wrote of his future wife: “I had only to open my window and blue air, love and flowers entered in with her.”

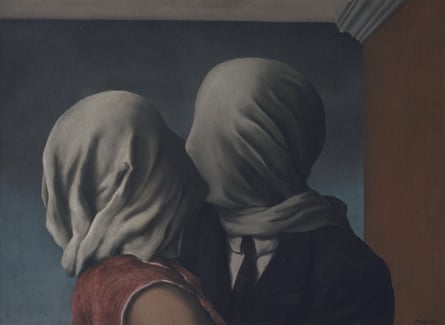

7 | Magritte

The Lovers (1928)

A blind date? Two lovers are trying to kiss through their separate grey hoods, lips never meeting, the cloth dry and suffocating on the tongue. They cannot see each other, they cannot feel each other and they cannot even kiss: it’s a masterpiece of sexual frustration. But the cornice above their heads suggests the bourgeois imprisonment of a couple glued together by convention yet also blocked by each other. Perhaps they don’t know each other at all. It’s the nightmare of a lonely relationship. Those hoods could double as shrouds.

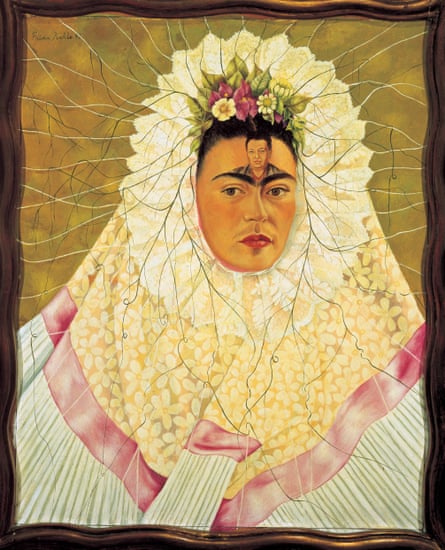

8 | Frida Kahlo

Self-Portrait as a Tehuana (1943)

This double portrait was begun in the late summer of 1940 after the artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera divorced. As so often, Kahlo makes metaphor literal. Diego is on her mind, tattooed on her brain, locked inside her head despite all the agony of his extramarital affairs. She cannot stop thinking about him. She wears the traditional Mexican costume he loved and a crown of leaves that seems to spread like a web, as if Kahlo was trapped in both the picture and the obsession. But that was not the end of their love. By the time the picture was finished, in 1943, they had remarried.

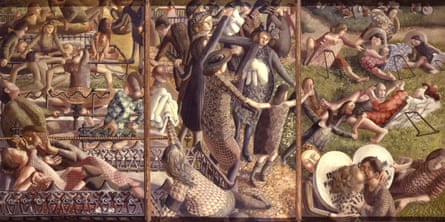

9 | Stanley Spencer

The Resurrection: Reunion (1945)

When it is all over in this world, what next? Larkin says all that survives of us is love, but in Stanley Spencer’s wondrous (and homely) vision of the Resurrection based on Port Glasgow cemetery, this love is not just some poetic notion but a great full-body hug. The lovers in the foreground, seen embracing against what looks like a gigantic Love Heart sweet, suitably inscribed, are brought back to life in the moment of a kiss. We will see each other again and our love will never die. It might be what we all hope for… and after all, who knows?

10 | Robert Indiana

Love (1965)

The word spells love. But the picture is far more than a word. That lovely round O, beside the upright L and carried by the bracing E, takes on a bodily form. It swoons, it leans, its head has been turned. It flirts. It has been knocked sideways by love. The American pop artist Robert Indiana created a pure and concentrated modern pictogram with this surpassingly famous painting, lettered in the colour of love against a blue and green landscape. The image has sold by the million, a valentine for our age. Love – what else matters?