|

Exploring Global Variations in Suicide Rates: A Sociological Perspective Greg Smith, Howard Community College Mentored by: Greg Fleisher, M.S. |

Abstract

This article investigates the differing suicide rates from contrasting cultures across the world – namely the United States, and South Korea – based on data from multiple demographics of people, and asks: why are there such significant and noticeable differences between these groups? Using a meta-analysis approach, this article uses research findings from across the globe to try and understand where similarities and differences can be found in suicide statistics. Throughout this article, attempts are made to find strong correlations between suicide and sociological factors from various cultures and demographics of people, not to establish a concrete cause for suicide, but to infer that some factors may make certain people more susceptible to suicide than others. Sociological theories are applied to various types of suicide when appropriate. In doing so, the findings and suggestions within this piece may be useful in finding ways to slow or stop the crisis of suicide across the world.

Introduction and Method

Suicide is the act and consequence of intentionally taking one’s own life, and it is a devastating issue in many societies today, with an estimated 703,000 deaths by suicide occurring globally each year [1]. While some countries experience relatively low suicide rates, other countries are seeing very high numbers, like the Republic of Korea’s 28.6 per 100,000 in 2019 [2]. For reference, according to the World Health Organization, the United States stood at 15.6 deaths by suicide per 100,000 people in 2021 [2]. Figure 1 [3] illustrates some examples of vast international differences in suicide rates.

Figure 1: Variations in suicide rates in a select group of countries in the year 2021, visualized by country and then split into male/female suicides per 100,000 population.

This paper investigates the potential sociological explanations for the vast differences between suicide rates in various countries, making comparisons between sociocultural demographics such as gender, socioeconomic status, and race, and raising further questions about what factors might be affecting these differences. To highlight contrasting cultures, the focus of this paper will be the differences between South Korea, and the United States. However, it should be noted that researchers cannot fully establish causes, and each suicide is different – it is especially hard to research suicide due to the inability to interview, question or study people after they have taken their own lives. Therefore, most of the data from which researchers can interpret meaning from is correlational, rather than causational.

This paper is a meta-analysis, meaning no field research has been carried out – rather, it uses the findings of other research studies to make comparisons, correlations and potential conclusions. This paper pulls together research studies and reliable sources on suicides in order to comment on what their potential causes, variations, and potential solutions might be.

Therefore, the limitations around studying suicide apply to all of the research used in this paper. Furthermore, the majority of this paper serves as a traditional “results” section, as the intent is to analyze the work of other researchers.

Due to the negative connotations of the phrase “committing suicide,” this paper will refrain from using this term, using terms such as “die by suicide” in its place.

The Sociology of SuicideMany sociologists have attempted to explain what compels people to attempt suicide, and explain the different types of suicide. Emile Durkheim, an important sociologist in the emergence of sociology, had many thoughts on suicide and the sociological explanations for it, theorizing there are various different kinds of suicide [4]. One type of suicide, egoistic, determines that some people may engage in suicide due to an isolation or alienation from their society, feeling they do not have a place within it. Commonly these people may be referred to as outcasts, or loners.

Another type of suicide is referred to as anomic suicide; these suicides are explained by a lack of stable structure within the person’s social environment, which would otherwise give the person a sense of belonging and a meaning to life, such as religion or family. Durkheim saw anomie as being able to match or integrate with a group’s system of social norms. Through many of Durkheim’s theories on suicide, the main theme is that “the more thoroughly a person belongs, the lower the risk of suicide” [4]. This would suggest that social support networks, and close relationships with others, are some of the most important factors in preventing suicide.

Robert Merton elaborated on Durkheim’s ideas of anomie, suggesting that it is a form of strain theory – the theory that society pressures people to commit deviant behaviors [5]. This would imply that suicide is the action people may take as a result of pressure from the inability to meet their goals; these goals are usually placed on a person by the society they live in, based on what is highly valued within a society or culture.

Within this paper, these sociological explanations, among others, will be examined and compared to try and describe and explain why certain aspects of society may lead to certain types of suicide.

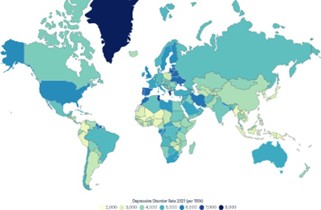

Mental Health

The topic of suicide is commonly associated with depression, and other mental health disorders, which is understandable, as up to 60% of suicides are linked to major depressive disorder [6]. Figure 2 [7] shows a world map of depression rates, detailing that the United States is almost twice as depressed as South Korea, per 100,000 people. Why, then, are such high rates of suicide seen in a country like South Korea, which has such a low diagnosis of depressive disorders?

Figure 2: A world map showing depression rates for each country per 100,000 people in 2021.

This leads onto the first major sociological factor of suicide: stigmatization. In South Korea, symptoms of depression are still prevalent in the population, and yet the rate of diagnosis is low because of the stigma their society has placed on those with mental health disorders. Even when being tested for depressive symptoms via a questionnaire, it was found that South Koreans tend to respond with more socially acceptable answers and are less likely to acknowledge their own symptoms, hence their lower diagnosis rate [7], as they are overly self-conscious of what others may think.

Viewing depression (and its treatment) as shameful or weak has resulted in a lack of willingness to seek a diagnosis, out of embarrassment and shame, as people may not want to be labeled or seen as different. This supposed “shame” can be seen as a family shame, and a stain on a family’s good name, which may lead to the family denying their relative’s mental illness altogether, as has been commonly seen in China [8]. All of this discouragement may even lead their depression to worsen, therefore resulting in more suicides.

To choose to attempt suicide due to stigmatization – and being afraid to stand out as different in a negative way – could be argued as being an indirect contribution to altruistic suicide. If one believes they are bringing shame upon their family, or social group, their eventual suicide may be seen in their minds as necessary to stop themselves from disrupting the harmony or reputations of their social networks.

This can be contrasted with the societal attitudes to mental health in the United States, a country which actively encourages people to seek help with disorders such as depression – as do many Western cultures. While not entirely stigma-free, the U.S. is far more welcoming of those suffering with mental illnesses, as is reflective in many campaigns, and the significant amounts of Americans utilizing therapy, even though they may not suffer with depression. As a result of their advocacy for treatment and support, 61% of adult Americans diagnosed with major depressive episodes sought treatment in 2021 [9], whereas only 27.38% of South Koreans sought treatment or counseling for their diagnosed depressive disorders between 2017 and 2020 [10].

This is a difference that is consistent when comparing most Western countries against Eastern countries, as the stigma and lack of understanding or support for the mentally ill can be seen in China, Japan and India, among others. This may be due to the collectivist nature of these countries; since social image is of great importance to Asian cultures, people do not want to jeopardize their place within their societies or become shunned by others. Collectivism, as opposed to individualism, is the concept of interdependence and social harmony, putting a greater focus on the needs of a group, rather than those of an individual. Therefore, standing out as different from the majority is not necessarily a good thing in these cultures. The sociological concept of the looking-glass self – how people measure their own self-worth from the judgments of other people – relates to this severe stigma, as people in Eastern cultures appear to feel a greater shame from the judgment of others. Therefore, they do not seek help, for fear of being judged and losing “face.”

Access to Healthcare

Stigmatization isn’t the only thing preventing people from seeking treatment – being able to access necessary healthcare is a challenge in itself. In the United States, a lot of important and effective mental health resources require people to have health insurance, which can be costly, and may even rely on the client’s employment status. Healthcare is not universal, or socialized, meaning those with lower socioeconomic status are in a worse position to receive adequate healthcare, both physically and mentally. In the United States, those who are uninsured have shown positive correlations with suicidal ideation and suicide rates than those with health insurance [11], with similar findings in China linking depression with a lack of insurance [12] – putting these people further at risk of becoming suicidal.

This is being seen in South Korea too; up until recently, mental healthcare was separate from primary care, which may have made it more inaccessible, as well as further enforcing the stigma surrounding treatment in South Korea. Despite the current lack of utilization of these services, there is no shortage of available mental healthcare in South Korea – people are seemingly unable or simply unwilling to use it. In late 2023, South Korea introduced a new plan to offer mental health checkups to young adults every 2 years, in hopes to address its high suicide rate issue [13]. With more emphasis on mental healthcare, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic of the early 2020s, there is a chance the stigmatization of mental illness can be lessened with this new generation of mental health-conscious young people.

Gender

It is not just international differences that should be considered here – there are plenty of societal factors that are near-universal internationally, such as the similarities in gender. In 2021, almost 4 in 5 suicides in the United States were by males [14], a trend mirrored in the United Kingdom with male suicide being three times as likely as female suicide [15], and again in South Korea with statistics finding men to be twice as likely as females to die by suicide [16]. Figure 1 helps to visually highlight these differences. The question is, why?

In the United States, women are more likely to attempt suicide than men, but men tend to use more violent methods, therefore successfully completing suicide more [17]. For example, 6 out of 10 gun owners in America are men [18], which may be a factor in this gender imbalance regarding suicide. Suggestions have been made that culturally enforced gender roles play a part in this, with women choosing non-violent methods in order to preserve their appearances [17]. It may just be that non-violent methods, such as overdosing, are simply not as effective at completing suicide, which is why women survive their attempts more than men do.

It is also theorized that men often use more violent methods because while women may be more likely to experience suicidal thoughts, men tend to have more genuine intent to die when attempting suicide. These findings are also seen in patterns within South Korea, as more females are admitted to the hospital from suicide attempts than males, yet more men actually die from their attempts. This is because while the most popular method of suicide is the same across genders in South Korea – ingestion of chemicals – men tend to use more harmful chemicals, in higher doses [19].

If there is truly more intent by men to die, why would men feel more willing to commit harder to these suicidal thoughts? Again, this may be linked back to stigmatization. While mental health support may be increasing in Western countries, there is still a stigma that men ought to “man up” when facing mental health issues, and tough it out; a stigma that is socialized onto boys from a very young age by previous generations, who didn’t have anywhere near as much mental health support available as today in Western cultures. Men also tend to struggle more to talk about their emotions, and therefore find less social support as well as reaching out less often for medical help [15].

Because men find it difficult to reach out for help, they may turn to substances, or alcohol, for comfort. Men are twice as likely as women to meet the criteria for alcohol dependence in the United States [18], and alcoholism can increase the risk of suicide. The consensus varies, but statistics show that around 25-40% of suicide victims are found to have had alcohol in their systems at the time of suicide. Alcohol can also increase impulsivity [18], which is already stereotypically higher in males, and therefore might add to the suicide risk. Impulsivity is a characteristic highly associated with anomic suicide, as anomic suicide often comes from a sudden negative change of circumstances, which is also a leading cause for alcohol consumption. Therefore, it can be suggested that stigmatization and less social support makes the risk of death of suicide more likely in men globally, despite more suicide attempts being seen in women.

Collectivism

Many Asian cultures are collectivist, meaning that there is a priority placed on social harmony, and the success of a whole group, rather than each individual within it. Looking at Durkheim’s theories, there are a few ways they can be applied here when questioning the differing suicide rates by country. Because South Korea is a collectivist culture, family ties are normally strong, which would suggest that collectivism plays no role here, as social support reduces the likelihood of suicide. However, a South Korean study [20] found that disturbances in family intimacy were the most powerful predictor of a suicide attempt among those who had depression, suggesting that perhaps collectivism emphasizes and increases the effects of a potential family dispute, making the family disturbance more upsetting and therefore increasing the likelihood of anomic suicide. Egoistic suicide, as described earlier, can be the result of being outcast or isolated from social support networks. Therefore a familial dispute, or even the end of a relationship or friendship, may be more likely to have this effect in a collectivist culture.

In collectivist cultures such as South Korea’s, increased pressure is put on people to succeed from a young age, by parents, academia, and society [21]. Not only does this pressure affect young South Koreans’ health by default, but it makes this much worse when things like grades, or social approval starts to slip. With poor grades, South Koreans find their career prospects waning and parental disapproval increasing, and this pressure would certainly seem to stop them from reaching their goals, which may apply to Merton’s thoughts on anomie. In the United States, while academics and grades are still seen as important, there is less pressure or shame placed on a student should they fail to find success – school is not the be-all and end-all, as American culture encourages a range of alternative ways to be successful. Academic excellence in the States is celebrated, but not necessarily expected, so the pressure and strain is not as high as that of countries like South Korea.

Because collectivist cultures seek to maintain order and social harmony, historically there have been examples of Durkheim’s other named type of suicide, “altruistic,” in which individuals self-sacrifice for the self-perceived betterment of the society they belong to. This may be most notably associated with Japanese culture, from which “kamikaze” and “seppuku” are terms famous even in Western culture. These are not common practices in modern times; however, according to a 2015 study, suicides in Japan masquerading as seppuku are still at a high level in modern times, despite it being an ancient samurai ritual [22]. Self-sacrifice for honorable causes is not something that Western culture has experienced much – unless we consider war to be suicide – but the West does still see it in acts of martyrdom, such as the self-immolation of pro-Palestine protester Aaron Bushnell in 2023.

Discrimination

Race and ethnicity represent one further sociological explanation for differing suicide rates. A trend seen in many cultures is that ethnic minorities tend to have a greater suicide risk, and this can be seen in both the United States and South Korea. Myung-Bae Park [23] found that within South Korea, adolescents with both parents born outside of South Korea had the highest rate of suicidal ideation out of all demographics, at 24.7%.

Sociological factors must be at play here, and there are a few key ones that come from racial discrimination – an aspect of sociological conflict theory, which focuses on inequality, and could be applied to the historical power struggle between white people and ethnic minorities in the United States. Of course, when discriminated against because of their race, people are likely to feel like outcasts, and isolated from the majority of their population. As previously discussed, social isolation and a lack of belongingness within a society is a potential explanation for egoistic suicide and can increase the risk of such. However, anomic suicide may instead be a better explanation for suicides influenced by racial discrimination, as institutionalized racism equates to a lack of consistent rules within a society that can leave a person feeling excluded – such as the inconsistent treatment of people within different racial demographics.

Another factor brought on by discrimination that may explain this trend is socioeconomic standing. As ethnic minorities in the United States have historically lacked equal access to housing, education, and career opportunities, there is an increased likelihood of poverty within these demographics, which acts as a cycle that is hard to escape from. Poverty, financial instability, and homelessness can also increase suicide risk [24]. All of these potential results of discrimination can also contribute to further discrimination, in the form of lacking quality healthcare, which as mentioned earlier in this paper can further increase suicide risk as there is less likelihood of being insured, or on a good healthcare plan.

Suicide brought on by socioeconomic discrimination would also be considered anomic suicide, as again it constitutes a disconnect from consistent social structures, witnessing the treatment of others and understanding them as different from one’s own treatment, therefore feeling alienated by society. This would also relate to the concept of strain theory, as the likelihood of the deviant act of suicide would be increased by something like poverty, due to a struggle to achieve the culturally valued goals of wealth and racial equality.

Climate

One might assume that bad weather could affect the suicide rate, with rain and gray skies feeling like an outward representation of the depression that might lead somebody to attempt to die by suicide. However, an unexpected similarity that seems to appear globally is that when the temperature increases, so do suicide rates. Cheng et al. [25] found that when the temperature in California increased by 1 degree Celsius, the expected suicide rate increased 0.83% when accounting for factors such as typical trends within the counties being studied. Warmer temperatures are associated with higher stress, irritability and impulsivity, which might account for this slight increase.

Similarly, Likhvar et al. [26] found that when temperatures in Japan increase, the suicide rate increases on that very same day. Likhvar et al. also discovered that this increase came predominantly from violent methods of suicide, finding that there was no significant change in the rates of non-violent suicide when temperatures increased. South Korea would also seem to follow this climate-based fluctuation in suicide rates, with a seasonal pattern showing peaks in spring, as temperatures began to increase, and troughs at the beginning of winter, as temperatures begin to decrease [27]. This may be because high temperatures are associated with physical and mental exhaustion, as well as negatively impacting sleep, all of which can have a negative impact on our mental health, making the risk of suicide more likely [28].

This can be considered a sociological issue, as climate change – an issue that affects all societies – can be seen as a contributing factor to this small but real effect of increasing temperatures. The increased risk of severe weather events, heatwaves, and overall global warming, may be an indicator that suicide rates due to climate factors are only going to increase in the coming years.

Methods of Suicide

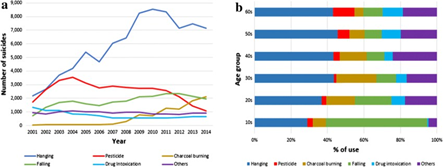

Methods of suicide themselves can also be considered sociological – how a person chooses to end their own life can be reflective of their environments. In South Korea, the most popular method of suicide among 9-18 year olds is jumping from a high place [29], whereas in the United States, rather predictably, firearms were a leading method of adolescent suicide in 10-19 year olds [30]. Figure 3 [31], from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, helps highlight the prevalence of firearm suicide among all American suicides in 2022, and Figure 4 [32] shows methods of suicide in South Korea across all age groups – notably missing a firearms section, due to its rarity.

Figure 3: The most utilized methods of suicide in the United States in 2022

Figure 4: The most utilized methods of suicide in South Korea, from 2001-2014.

This would suggest that people use the methods that are more commonly accessible to them, since it is common knowledge that the United States has more guns than it has people, and South Korea is known for its tall apartment buildings due to the dense populations within its cities.

These findings lead us to a controversial but important issue among the United States; if people didn’t have access to firearms, would the rates of suicide decrease, or would people with suicidal ideation just use other methods? It could be suggested that because death by firearm is considered ‘painless’, as it is quick and easy, taking this method away leaves few suicide methods that aren’t extremely painful or slow, and therefore may discourage suicide in the United States.

It might be possible to speculate on why someone chooses a certain method of suicide, based on their motivation to attempt suicide in the first place. For example, should a person choose a quiet, less violent method such as hanging, this could reflect an egoistic intent – a lack of social networks and high isolation levels. Alternatively, anomic suicide often comes from a frustration at lack of social regulation, meaning these suicides may opt for more violent or public methods, partly due to the impulsivity of the decision, and partly due to their frustration towards the society that has failed them. Figure 4 shows that a large number of suicides in South Korea are made up of hangings; this might support the thought that social isolation in collectivist societies increases the likelihood of egoistic suicide.

Conclusion

Throughout this paper, many contributing factors have been discussed that seemingly correlate with suicide rates, leading to possible conclusions on how to lessen this serious issue. It seems that with acceptance, treatment, and an increase in mental healthcare, stigmatization around mental health issues can be reduced, which may in turn reduce depression and suicidal thinking. Societies also ought to put a focus on a sense of belonging, ensuring that people have social support groups or family to turn to in times of need, as Durkheim’s theories of suicide relate to a lack of belongingness.

Both stigmatization and social support networks could be improved for those struggling with mental illness, especially when concerning suicidal men, which is gaining momentum in Western society with the support of mental health charities. Accessibility to fast and easy means of suicide, such as firearms, may also need to be assessed – especially for adolescents, who should not be able to access weapons and dangerous substances. Racial discrimination is hard to eliminate, but it is apparent that there are more issues from racism than appear at surface-level.

Again, it must be stated that the studies cited and research used is correlational, and only makes suggestions as to what may affect various suicide rates. Many people experience the difficulties discussed in this paper and choose not to attempt suicide, and may not even consider it in the first place. In contrast, many people die by suicide having not experienced the factors that this paper suggests would increase the likelihood of suicide. Suicide is hard to study due to a difficulty establishing clear motivations, and differs on a case-by-case basis.

There is clearly no easy fix to the suicide crisis, no matter which country is examined, but it seems that the world is coming together and starting to take action. More awareness of these issues is a great first step to tackling them, and one must appreciate that society has some changes to make. One thing is for certain: suicide is a global issue, no matter the international differences, and there will always be more work to do.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Fleisher for his help and support on this project, as well as Dr. Cheryl Campo and everybody working at Schoenbrodt Honors, for allowing me to be a part of the Honors society and encouraging me to work as hard as I have across my time at HCC – I am very grateful for the opportunities and experiences that have come my way because of my involvement in this Honors program.

Contact: gsmith@howardcc.edu, gregsmith99afc@gmail.com

References

[1] World Suicide Prevention Day 2022. (2022). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-suicide-prevention-day/2022#%3A~%3Atext%3DAn%20estimated%20703%2C000%20people%20a%2Cprofoundly%20impacted%20by%20suicidal%20behaviours

[2] Suicide mortality rate (per 100,000 population). (2019). World Health Organization. https://data.who.int/indicators/i/16BBF41

[3] Fleck, A. (2024). Suicide rates around the world. Statista. https://www.statista.com/chart/15390/global-suicide-rates/

[4] Comer, R. J., & Comer, J. S. (2022). Fundamentals of Abnormal Psychology (10th ed., pp. 210-237). Worth Publishers.

[5] Zhang J. (2019). The strain theory of suicide. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, Volume 13, e27. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/prp.2019.19

[6] Chung, W. M. N., Choon, H. H., & Yin, P. N. (2017). Depression in primary care: assessing suicide risk. Singapore Medical Journal. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2017006

[7] Lee, J., Kim, H., Hong, J. P., Cho, S. J., Lee, J. Y., Jeon, H. J., Kim, B. S., & Chang, S. M. (2021). Trends in the prevalence of major depressive disorder by sociodemographic factors in Korea: Results from nationwide general population surveys in 2001, 2006, and 2011. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 36(39), e244. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8506416/

[8] Parker, G., Gladstone, G., & Chee, K. T. (2001). Depression in the planet’s largest ethnic group: the Chinese. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(6), 857–864. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.857

[9] Major Depression. (2023, July). National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression#%3A~%3Atext%3DIn%202021%2C%20an%20estimated%2061.0%2Ctreatment%20in%20the%20past%20year

[10] Lee, J., Choi, K. S., & Yun J.A. (2023) The effects of sociodemographic factors on help-seeking for depression: Based on the 2017–2020 Korean Community Health Survey. PLoS ONE 18(1): e0280642. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280642

[11] Tondo, L., Albert, M.J., & Baldessarini, R.J. (2006). Suicide rates in relation to health care access in the United States: an ecological study. J Clin Psychiatry. 67(4):517-23. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0402. https://www.psychiatrist.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/18010_suicide-rates-relation-health-care-access-united-states.pdf

[12] Tian, D., Qu, Z., Wang, X., Guo, J., Xu, F., Zhang, X., & Chan, C.L. (2012). The role of basic health insurance on depression: an epidemiological cohort study of a randomized community sample in northwest China. BMC Psychiatry. 20;12:151. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-151. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3532421/#%3A~%3Atext%3DThe%20percentages%20of%20participants%20with%2Cin%20the%20follow%2Dup%20surveys

[13] Park, J-H. (2023, December 5). South Korea unveils plan to tackle ailing mental health. The Korea Herald. https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20231205000693

[14] Suicide data and statistics. (2022). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/suicide-data-statistics.html

[15] Kirk-Wade, E. (2025, January 8) Suicide statistics. House of Commons Library. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7749/

[16] Yoon, L. (2023, November ) Number of suicide deaths in South Korea from 2010 to 2022, by gender. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1267022/south-korea-suicide-deaths-by-gender/

[17] Freeman, D., & Freeman, J. (2015, January). Why are men more likely than women to take their own lives? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/jan/21/suicide-gender-men-women-mental-health-nick-clegg

[18] Schumacher, H. (2019, March 17). Why more men die by suicide than women. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190313-why-more-men-kill-themselves-than-women

[19] Hur, J. W., Lee, B. H., Lee, S. W., Shim, S. H., Han, S. W., & Kim, Y. K. (2008). Gender differences in suicidal behavior in Korea. Psychiatry Investigation, 5(1), 28–35. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2796090/

[20] Lee, J.-Y., & Bae, S.-M. (2015). Intra-personal and extra-personal predictors of suicide attempts of South Korean adolescents. School Psychology International, 36(4), 428-444. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315592755

[21] Hawk, W. (2023, March). Students in South Korea begin to value self-care amid academic pressures. The Diamondback. https://dbknews.com/2023/03/28/students-south-korea-self-care-academic-pressures/

[22] Pierre, J. M. (2015). Culturally sanctioned suicide: Euthanasia, seppuku, and terrorist martyrdom. World Journal of Psychiatry, 5(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.4, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4369548/#%3A~%3Atext%3DSeppuku%2C%20the%20ancient%20samurai%20ritual%2Cout%20both%20there%20and%20abroad

[23] Park, M-B. (2024). Suicide risk among racial minority students in a monoethnic country: A study from South Korea: Suicide risk among racial minority students. Archives de Pédiatrie. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0929693X23001811

[24] Inequality and suicide. (2024). Samaritans. https://www.samaritans.org/about-samaritans/research-policy/inequality-suicide/#%3A~%3Atext%3DPeople%20living%20in%20the%20most%2Cis%20a%20major%20inequality%20issue.

[25] Cheng, S., Plouffe, R., Nanos, S.M., Qamar, M., Fisnam, D.N., & Soucy, J-P.R. (2021) The effect of average temperature on suicide rates in five urban California counties, 1999–2019: an ecological time series analysis. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-11001-6#citeas

[26] Likhvar, V., Honda, Y. & Ono, M. (2011). Relation between temperature and suicide mortality in Japan in the presence of other confounding factors using time-series analysis with a semiparametric approach. Environ Health Prev Med. 16, 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-010-0163-0, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12199-010-0163-0#citeas

[27] Nam, J., Sim, H. B., Lee, J. Y., Kim, S. W., Kim, J. M., & Ryu, S. (2022). Changing Seasonal Pattern of Suicides in Korea Between 2000 and 2019. Psychiatry Investigation, 19(4), 320–325. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2021.0387, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9058267/

[28] Shoib, S., Hussaini, S. S., Armiya’u, A. Y., Saeed, F., Őri, D., Roza, T. H., Gürcan, A., Agrawal, , Solerdelcoll, M., Lucero-Prisno Iii, D. E., Nahidi, M., Swed, S., Ahmed, S., & Chandradasa, M. (2023). Prevention of suicides associated with global warming: Perspectives from early career psychiatrists. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1251630. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10693336/#ref1

[29] Lee, S., Jhone, J. H., Kim, J. B., Kweon, Y. S., & Hong, H. J. (2022). Characteristics of Korean children and adolescents who die by suicide based on teachers’ reports. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6812. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116812

[30] Ormiston, K., Lawrence, W. R., Sulley, S., Shiels, M. S., Haozous, E. A., Pichardo, C. M., Stephens, E. S., Thomas, A. L., Adzrago, D., Williams, D. R., & Williams, F. (2024). Trends in adolescent suicide by method in the US, 1999-2020. JAMA Network Open, 7(3), e244427. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.4427

[31] Suicide data and statistics. (2024). CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/data.html#cdc_data_surveillance_section_6-suicide-methods

[32] Kim, , Kwon, S. W., Ahn, Y. M., & Jeon, H. J. (2019). Implementation and outcomes of suicide-prevention strategies by restricting access to lethal suicide methods in Korea. Journal of Public Health Policy, 40(16). DOI: 10.1057/s41271-018-0152-x