7 Roles that Sources Can Play

Sarah Johnson and Jeremy O'Roark

At some point in your academic career, you will be asked to move beyond merely reporting on the findings of sources, as you would in a bibliography, and instead to use what you have learned from sources to participate meaningfully and responsibly in an academic conversation. This may be a literal conversation or one that takes place in writing as writers read and respond to one another.

All academic writers must show how what they know or what they claim connects with prior information or knowledge. This is true even when these scholars are presenting a new study or their own new findings. Sometimes, academic writers contribute to what we know or understand about a subject by presenting their own position, or argument, in an ongoing debate. At these times, they must use perspectives and information from others to support or provide evidence for that position. This is a skill that you will practice as a composition student.

Finding credible, relevant sources (as described in the chapter, “Finding and Using Outside Sources”) is only one part of the research process; effectively integrating those sources in the arrangement of an academic or argumentative essay is a different task requiring further close reading and critical thinking. This book highlights three skills of academic writers as they work with sources:

- Considering the different roles that sources can play in your argument (this chapter)

- Synthesizing, or connecting information from multiple sources in unique ways

- Providing context for your reader about each source and how it fits into your argument

In this Chapter

1. Good Research is a Process that Starts with Inquiry

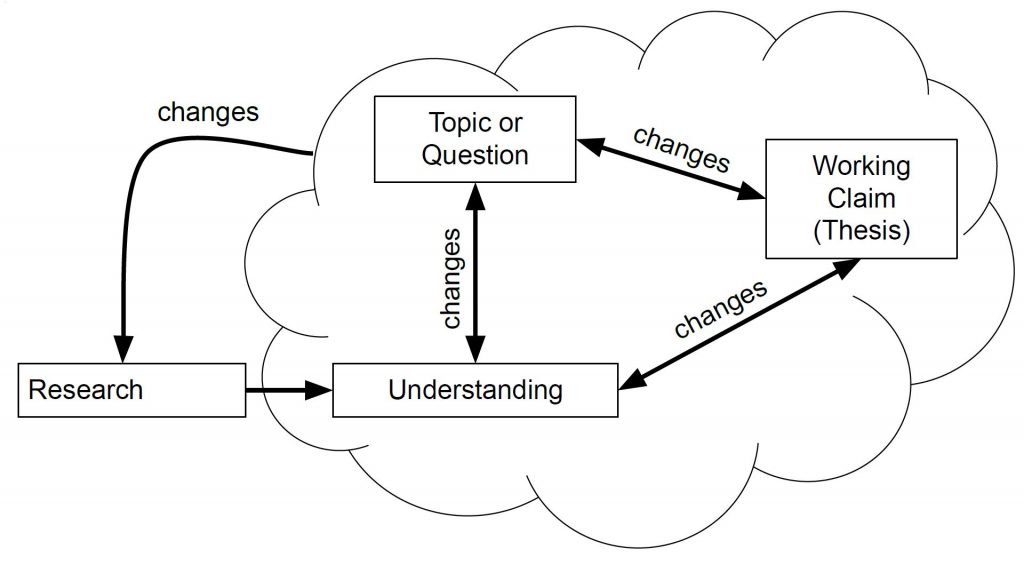

Good research starts with a question; you have an idea about something, and you want to learn more. Academic research is a specific type that involves finding and reading sources to prepare to participate in an academic conversation. This requires you to keep three elements in your mind and to stay aware of how they are changing, and how they are changing each other, as you learn more (figure 1):

- your central research topic or question

- your knowledge or understanding about the topic

- your working main claim or position about the topic (working thesis)

To evaluate whether a source is relevant for your purpose, you should not just try to decide whether it “fits” or relates to what you already know or believe. In fact, that source’s perspective may change what you believe. Or, it may change your entire question or topic itself, as you learn about specific issues, conversations, and debates related to the question that you started with.

Example of Research as a Recursive Process

Imagine that you start with a broad research question: “are the graduation rates really so low for college students in the United States?” After some preliminary research, you learn that, yes, there are some statistics that highlight a problem of students starting but not finishing college.

So, you narrow your research question to learn more: “what factors contribute to students’ struggles with completing college?” And you start to see that there is an ongoing conversation about students from under-served populations: low-income students and first-generation students in particular.

So, given all your findings, you write a working thesis that might sound like this:

Example Working Thesis: First Draft

The promise of college as a gateway to increased financial earnings or lifelong success for its attendees isn’t panning out; more needs to be done to address completion rates for college graduates—especially among under-served populations, including students from low-income households.

Remember: your initial topic was graduation rates, and that shifted to a topic about why students struggle to finish college. While you are researching, keep in mind that the many ongoing conversations about higher education might not immediately “match” or sound just like your own search terms or topic. So, skimming articles and texts about your overarching topic—college—can still be valuable. Look at the article in figure 2 and note the title: it seems to be asking about the possible effects of free college tuition. It doesn’t look like it will “answer” your research question, but it can still prove useful.

As you skim this source, you find that, as the title implies, these authors argue that making college free is not “enough to ensure college success” because low-income students face more complex struggles than just the difficulty of affording college. So, even though your working thesis does not directly relate to the main claim or thesis of this article, it contains relevant perspectives and evidence about your topic.

Similarly, if your working question or topic is why low-income students struggle in college, then the article in figure 3 may not seem to answer your question directly. Instead, it appears to be about why a New York college’s “accelerated” associate degree programs should be used as a good model for making a policy for the whole nation. But, if these authors are arguing that their college has made a successful “pathway out of poverty,” then maybe part of their article first describes the problem that you are researching (low-income student struggles) before arguing for their specific solution.

After reading these and other sources, you should revisit and revise your working claim or thesis statement to reflect all that you have learned and the likely position that you will take in your argument. Note the changes between this one and the previous example:

Example Working Thesis: Second Draft

Because low-income students do not complete college at the same rate as their peers due to several “hidden” barriers, American community colleges should redesign the ways in which they educate and support students from low-income households in order to meet the goal of putting those students on the path to increased financial earnings and lifelong stability.

Key Takeaways

As you research, your working thesis should remain flexible. You may start with a suspicion or be leaning in one direction, but you should enter into the process with an open mind, ready to learn more about the issue so that you fully understand it, so that you can see multiple perspectives, and so that you can join the conversation with your own writing.

2. Rereading Sources with their Roles in Mind

Once you have reached the step of preparing to “join the conversation” with your own writing, review how all of the perspectives and information that you have gathered relate or “speak to” your working thesis statement. How will you organize and present all that you have learned to your reader to persuade them effectively?

You are already familiar with the idea of a text appealing to readers by providing logical reasons, conveying credibility, and evoking an emotional response. So you can think of the perspectives and information from your sources as tools that strengthen these rhetorical appeals of your argument. But sources can serve in more specific ways, too.

Sources often provide evidence to support the claims within your argument. There are different kinds of evidence that are persuasive in different ways:

- Numerical data and statistics such as the results of scientific studies or surveys

- Expert testimony: the views and ideas of experts who support your claims

- Stories and anecdotes: specific examples that illustrate the real human experience of your topic and elicit emotion

- Counterarguments: opposing viewpoints or ideas that otherwise challenge your claims, which you will refute or answer

Also, some sources may include background information that you must provide as a writer so that your reader is adequately informed about your topic. This may include:

- The scope or scale of your topic (where your topic is relevant and how widespread it is)

- Definitions of terms or explanations of unfamiliar concepts that are important to your argument

- The history of events that your reader must understand for a full understanding of why the topic exists in its present form

- Information that shows the timeliness or relevance of the issue (kairos) and why it is important right now

With all of your research available, it may help to check for gaps in your supporting evidence using a chart like the one in table 8.1.

| Source #1: Page and Kehoe | |

| Background/Kairos | Section 1: rates of enrollment increasing, but graduation rates low

Section 3: discussion about need for support that goes beyond financial assistance and discussion about what kind of support helps |

| Numerical data and statistics | Section 1: statistics about college attendance

+ also “only three in five completed their bachelor’s degree within six years” + contrast between students from high-income families who completed (3/4) and students from low-income families (under half) Section 3: statistics about success in one program “61-75%” Section 4: increase in AA degree from 18-33% |

| Expert testimonies | Section 3: quote attributed to Dell Scholars program, students need “ongoing support and assistance to address all of the emotional, lifestyle, and financial challenges that may prevent scholars from completing college.”

Section 4: Levin and Garcia explain cost/value of program |

| Stories and anecdotes | Section 2: Story about “Veronica” and her needs for childcare and additional financial guidance

Story about “Marcus” as a full-time student and also supporting a family |

| Counterarguments | Last 2 paragraphs address problem of “free tuition” as a solution to completion rates; possible counterargument to explore? |

This kind of graphic organizer lets you “see” how your research will (or will not) help you start to build and support your argument.

A successful academic argument will draw from multiple sources in a variety of ways. So to help you create your graphic organizer–and start outlining your argumentative body paragraphs–it’s important that you review your sources strategically to start seeing how they will serve you as a writer. Let’s take a look at an article we’ve used in some of our model paragraphs (in the next section of this chapter).

This is an article called, “Feet on Campus, Heart at Home: First-Generation College Students Struggle with Divided Identities,” and it’s written by Linda Banks-Santilli, a college professor. In our research, we were focusing on the struggles faced by students from low-income families, but Banks-Santilli notes that around 50 percent of first-generation students are low-income students, so this article seems relevant to our argument as well. When we reread Banks-Santilli, keeping the different roles sources can play in mind, we can add to our graphic organizer (Table 2):

| Source #2: Banks-Santilli | |

| Background/Kairos | Defines first-gen students, could use this in a separate paragraph about this population or explain that “About 50% of all FG students in the US are low-income.” |

| Numerical data and statistics | |

| Expert testimonies | |

| Stories and anecdotes | Section 3 – last paragraph: one student’s experience moving away to college and still helping parents with household finances |

| Counterarguments | |

It’s clear that this source, Banks-Santilli, doesn’t “serve” many parts of our thesis. This is because the focus of the article isn’t aligned with the focus of our argument. That doesn’t mean it isn’t a useful source in the creation and composition of our argument.

In fact, if you fill out a graphic organizer with all of your sources, you will be able to “see” quite a bit about what you have and what you need to make and support your argument. You will notice if there is an obvious lack of evidence, for instance, or a lack of counterarguments. You will probably not use everything you note in your graphic organizer in your actual essay, but the act of rereading sources critically to note how they can serve your argument will help you.

3. How Body Paragraphs Serve a Thesis

Students are sometimes intimidated by the prospect of a 6, 7, or even 10 page assignment. They can’t imagine they’ll have enough to say to fill that length. One way that may help tackle such a task is to consider a shift in your thinking: you’re no longer the researcher, you’re now the messenger, writing your own argument that explains and develops your thesis.

If we break down the thesis statement above we can see that there are several points to explain, claims to prove, and ideas to develop (Table 3), and these different parts will likely become different sections of your essay.

| Excerpt from thesis statement | Implications for body paragraphs |

| Because low-income students do not complete college at the same rate as their peers | First, this needs to be proven or demonstrated thoroughly to engage readers and prepare them for the rest of the argument. |

| due to several “hidden” barriers | The second half of this clause argues for the main cause of the problem—though it is not specified in detail—and this also needs to be explained and proven: what are the “hidden” barriers? What do readers need to know or understand regarding these obstacles to completion? What is the proof that these are the primary cause of the problem? |

| American community colleges should redesign the ways in which they educate and support students from low-income households in order to meet the goal of putting those students on the path to increased financial earnings and lifelong stability | This thesis ends with a “proposal” section: a call for change. It may be more complicated to support this:

Note: this thesis specifies community colleges, so the essay will likely focus on two-year institutions at some point in the argument. |

Exercise

In your own paper, you may want to identify different points or parts of your working thesis. If you take the time to do this, you will be able to start imagining the different parts or sections of your own paper:

- Do you mention a specific problem? Will you prove that problem? Give background information about it? Define terms? Explore and discuss the current status of the problem?

- Should you address multiple causes of that problem? Or do you intend to demonstrate the severity of that problem by discussing effects?

- Have you identified multiple populations affected by the issue that you are presenting?

Once you’ve clarified (for yourself) what, exactly, you will need to accomplish in your essay to support your argument, you may find it easier to start drafting paragraphs that address those separate points. In fact, it can be most effective to write a draft of your body paragraphs before revising your thesis statement and finally drafting your introduction and conclusion sections.

Final Takeaway

Don’t just randomly select source material because you are required to use quotes in your writing. Source information should be well-selected and have a clear purpose. And that purpose should be clear to your reader.

Additional Resource