Introduction

Sarah Johnson; Beth Caruso; and Nic Learned

Welcome to College Composition: An introductory letter to students

Why study composition when there’s Generative AI?

Generative AI is ubiquitous. We all have to grapple with how we feel about it and use it in various facets of our lives, including in our lives as writers.

But there is no shortage of criticisms against it. HCC Professor David Buck discusses its environmental impacts, ethical concerns about stolen intellectual property, and other issues in his article “Policy for AI Usage in ENGL-121.” And in his textbook chapter, “How Large Language Models (LLMs) Like ChatGPT Work,” Joel Gladd argues that the way that these technologies function creates problems related to “bias, censorship, [and] hallucinations.”

Some emerging research suggests that overuse or overreliance on generative AI chatbots can actually harm our thinking ability and output. For example, an MIT study, “Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task” examines the effects of student behavior when using tech tools as part of their processes. Aaron French asks, in an article from The Conversation, “Is ChatGPT making us stupid?” He answers: in some cases, yes, “when used uncritically.”

Taking College Composition at HCC, and working through the interactive activities, readings, and writing assignments along the way, will help you to develop not only a set of writing skills and strategies that you can apply in other classes, in your online life, and in your future career, but also the crucial skillset of being a critical reader and thinker.

The HCC faculty believe that reading skeptically and with confidence (and stamina – learning ways to stay focused when reading challenging texts) is a necessary life- and job-skill in the age of generative AI. Whether you embrace it or work to confront or combat the problems with generative AI, knowing how to read its output thoroughly is an indispensable asset.

We’ll end with Gladd’s conclusion here as he highlights the most important element of this discussion: you.

“Also, your voice—the unique melody of your thoughts, the individual perspective shaped by your experiences, and the deep-seated beliefs that guide your understanding—is a vital component of your writing process. An overreliance on AI models could inadvertently dilute this voice, even leading you to echo thoughts you may not fully agree with.” – Joel Gladd

In This Chapter

- Why Take College Composition

- Major Component of College Composition: Asking Questions

- Major Component of College Composition: Recursive Processes

- How This Course Will Benefit You

- What to Expect

- Major Component of College Composition: Sophisticated Use of Sources

- How to Succeed: Metacognition and Meaningful Engagement

1. Why Take College Composition

First, nearly every other major in college will require writing. That idea is an easy sell for text-heavy disciplines like history, psychology, religion, etc.. But for those of you math types—who see numbers as truth and the words that surround them as fluffy stuff—it can be a bit tougher to see how the ability to write well is necessary for you to succeed in your courses. We must admit that at first, it might not be. But as you progress through your major, you will find that writing becomes an increasingly integral part of your work—the part where you explain to us numbers-impaired folks what all those crazy equations mean and why we should care about them. Similarly, you aspiring engineers will have to explain how your work can be lucrative to investors, just as you cyber-security folks will need to convince your clients that you know what you’re doing. Further, the close study of writing and composing will help you develop strategies and stamina as a reader, which will serve you in all of your college classes.

The second (and more important) reason that you are here has to do with what makes writing such an energy-consuming task in the first place: writing the way you will be expected to write in this course requires creating knowledge and perspective that is new, which means going beyond memorizing facts, repeating the perspectives of experts, or regurgitating what your teacher said the day before. It means transitioning from passively consuming information to actively constructing it—from being on the receiving end of the knowledge that others have created to being a creator of knowledge yourself. All majors in college share this central aim for you to transition from simply learning about their discipline to actually contributing to it, though it may not be apparent in your first and second-year courses. And that is why you are here: to learn to become a critical contributor to a knowledge-making community, a quality that you will need, not only to succeed in your chosen major, but also to succeed in your chosen profession, and more broadly, to contribute to society actively and constructively. In a sense, it is less accurate to say that nobody majors in College Composition and more accurate to say that everyone does.

And so, the emphasis in this course won’t be learning how to construct grammatically-correct sentences (though grammar is part of it), nor will it be learning how to write the perfect five-paragraph essay (honestly, you can forget everything you’ve learned about those); instead, the emphasis will be learning how to contribute to a knowledge-making community—communities like the ones you will encounter in your other courses, regardless of discipline, but which you will also encounter in the professional and civic contexts you hope to be a part of after you leave college. In a nutshell, you are here to learn how to use the writing process to create knowledge and perspective that is useful to you and others.

2. Major Component of College Composition: Asking Questions

What do you learn about in a course that aims to help you transition from passively receiving knowledge to playing an active role in its creation? What concepts, skills, etc. comprise the central content of such a course? And most importantly, what will you have to learn to pass it?

The shortest possible answer to those questions: critical inquiry.

What is critical inquiry? If you ask 20 different instructors of College Composition to define it, you will likely get 20 different answers (we did and we did), but that transition from passively receiving knowledge to actively creating it begins now, so at some point, you will have to work out your own understanding, and yet you might take comfort in the fact that there are many acceptable definitions.

For now, it is enough to note the word, “inquiry,” which connotes asking questions and seeking something that is not already known. And the word, “critical,” which is not really negative in this sense but instead refers to critical thinking, which itself entails reflection, evaluation, and looking at an issue from multiple perspectives. As a process, Critical Inquiry thus begins with questions, it examines, engages, and evaluates others’ responses to those questions, and it results in the writer putting forward a provisional but informed response to his/her/their original research questions. This response should be useful to the writer, personally, but should also be useful to other researchers and stakeholders addressed or affected by the research topic.

In this course, you will thus learn to form questions and to use those questions to drive your research, your writing, and ultimately, what you contribute to the conversations taking place among people currently doing research around the areas you’re interested in.

3. Major Component of College Composition: Recursive Processes

In practice, and as you apply these lessons, we’ll ask you to let go of the myth (or dream) of a perfect first draft – a final product that sounds great and that you write, sentence by painstaking sentence, the first time you sit down to work on it. In fact, most of your teachers (and most creative writers and professional writers) know that when they sit down to tackle a serious writing project, they are going to produce a bit of a mess – a collection of ideas, perhaps, some interesting paragraphs, maybe, but certainly not a completed product. Instead, experienced writers seem to recognize that when we write, we’re writing to ourselves first, we’re figuring out our ideas and only starting to properly arrange them. We know that the thesis might still be a bit unclear, we know that we’re still learning and thinking about things – this is critical inquiry in action.

Knowing that the first draft will never be the final draft, well, it takes the pressure off. We can sit down, get started, trust that we’ll return later, and not worry so much about picking every “right” word or “sounding good.” Revisiting the draft, taking breaks, revising after getting feedback, these are all steps that will make the writing experience less stressful and, most likely, more successful. That’s what happens when we treat writing (and learning and critical inquiry and research in general) as a process.

In service of that process, you will learn about a few other things along the way:

- The reading process will help you read sophisticated texts in sophisticated ways.

- The writing process will help you produce sophisticated texts of your own through brainstorming, pre-writing, drafting, revising, and editing.

- Information literacy will help you to locate sources who have done research on the topics that matter to you, and it will help you to know which kinds to use and in what ways.

- Rhetoric—the study of persuasive writing, speech, and/or other media—will help you better understand the audiences, purposes, and contexts of those sources, and it will help you make strategic composing decisions in light of your own audiences, purposes, and contexts.

- Argument will help you analyze the arguments of your sources and will help you compose effective arguments of your own–arguments that will constitute your contribution to the conversations taking place among your sources.

- Genre will help you compose with mindfulness that the texts you read and the texts you write are always read through readers’ expectations.

- Academic writing conventions will help you write with fluency in the forms that you will use in your other courses and will give you experience contributing actively to a knowledge-making community.

- Multimodality will help you compose traditional and non-traditional texts with awareness of the ways in which non-alphabetic factors shape readers’ understanding of texts.

- Structure, grammar, and mechanics will help you to produce clear, cohesive, and sophisticated writing (as appropriate to your rhetorical situation).

That is an imposing and potentially intimidating list, but this text and your instructor will guide you through these skills that, we argue, are in fact quite natural to humans, who are inherently social, chatty beings, and for whom consuming and composing text is almost second-nature.

4. How This Course Will Benefit You

Here, at Howard Community College, we have seven learning objectives for this course.

Learning Objectives for College Composition

- Construct texts by working through varying stages of the writing process.

- Demonstrate awareness of audience, purpose, and context through making informed decisions about forms of appeal, style, genre, and modality.

- Exhibit knowledge of writing conventions related to expectations such as clarity, cohesion, organization, paragraph structure, grammar, and mechanics.

- Maintain a controlling purpose for research and writing that emerges from a clearly-defined research question.

- Locate, evaluate, and integrate appropriate sources accurately and fairly through paraphrase and direct quotation.

- Critically engage sources through interpretation, analysis, and/or critique in service of developing and supporting logical, well-defined claims.

- Document sources with in-text and works cited citations following current MLA, APA, or Chicago Manual of Style guidelines or other methods as appropriate to the rhetorical situation.

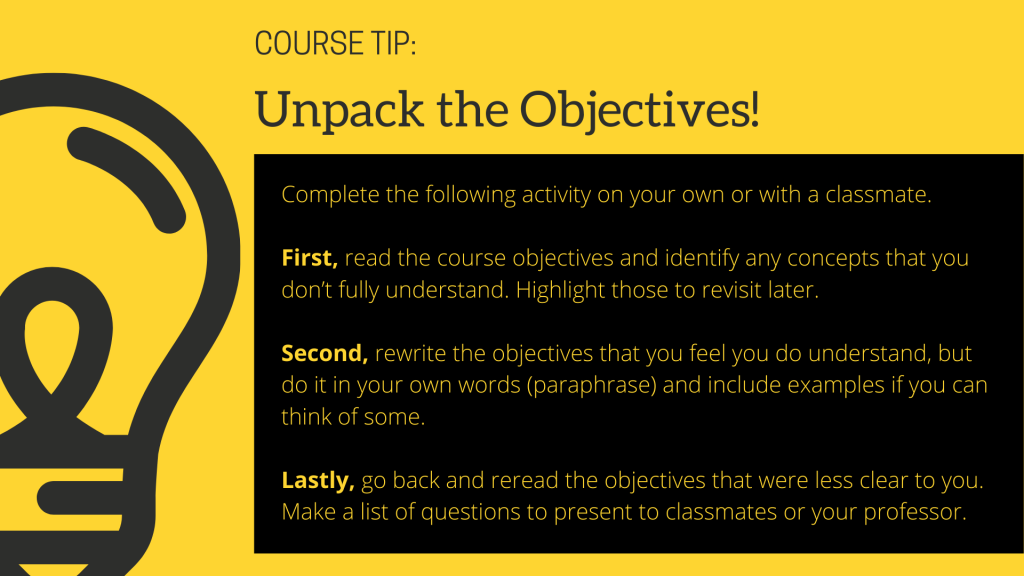

These course objectives, we like to point out to students, are written to a specific audience—namely, teachers of college composition and the different institutions our students might transfer to (so this course might satisfy another school’s required first-year composition course).

With that in mind, we think that it’s important that you, as the student of this course, start to think about what these objectives actually mean to you so you know what to expect and so you’re prepared to be actively involved in the different activities in the course.

There’s been a subset of research in the field of rhetoric and composition that looks at writing across disciplines (fields of study) or writing across curricula / contexts. Among other things, scholars study the role of writing in different types of classes and how the concepts and tools that students learn (or don’t learn) in a writing class will transfer (or not) into their other classes. So how will this course benefit you? We think it will help you in all of your classes and in many other facets of your life: personal and professional, as well as academic.

So, what good is a 100-level course? Well, in this course, you can learn certain habits to cultivate, certain steps or processes to work through, and certain questions to ask when faced with new or difficult writing tasks. In fact, there’s a researcher in our field, David Russell, who has a great metaphor about writing skills and the limiting notion that there are strict writing “rules” or “tools” that will help a student throughout all their future writing tasks. We’ll simplify this a bit, but Russell basically points out that if you’re good at one kind of sport (say football), you have certain “ball-handling” skills that likely make you so good at that sport. But if you were to try to apply those same skills to a game of ping-pong or golf, you’re not likely to be as successful, right?

Similarly, you’ll learn as we study texts in this class, there can be just as big a difference among a successful paragraph on a resume, one in a short news article, or one in a well-researched, “academic” argument essay. It may be a bummer that we can’t teach you the “rules” of “good” writing. But what we can explore in our College Composition course are the right kinds of questions and considerations to pose and evaluate that will help you better understand how start to write when you’re given new tasks in the future (Objectives #1-#4).

5. What to Expect

Students, we’ve learned, hate “busy work” and often just want to know “how long it has to be.” Students also prefer clear guidelines for homework assignments, and they seem to really love a detailed rubric.

Well: we have some good news and some “bad” news:

First, the good news: basically, if you treat all of the assignments in this course seriously–that is, if you tackle them thoughtfully and produce meaningful texts for all of the activities you’re assigned–you’ll be building your major assignments step-by-step so that you’ll never have to cram, rush, and pull an “all-nighter” starting from scratch. Phew, right?

More good news: we use Canvas assignments and modules in Canvas to present and collect all of the resources you’ll need to be successful in this course. We’ll present detailed assignments with what we believe to be clear and detailed instructions – it’s just up to you to 1) keep on top of your assignments, their due dates, and their expectations 2) learn how to navigate Canvas and check your HCC email for announcements, and 3) ask for clarification and help when you need it (including reaching out to HCC campus resources like tutoring.

And the “bad” news? Well, sometimes you might come across assignments that aren’t so clear-cut, or that have less detailed instructions than you’re used to seeing. Or, you may be assigned an essay that contains a holistic, comprehensive rubric rather than a point-by-point rubric. While this might feel a bit unsettling at first, think of it this way: you’re actually being empowered. When an assignment has fewer criteria, it can feel a lot less limiting, and you’ve been given an opportunity to own it. So, take the reins, think critically, be creative, and explore new possibilities with your coursework. That said, keep in mind that it’s perfectly normal to feel stuck or confused from time to time. If you’d like clarification on an assignment, don’t be afraid to send your professor a message in Canvas; your active engagement with the course material will surely impress them!

A note on your homework for this course:

Thinking is invisible. Unlike training as an athlete, running laps or lifting weights, where you can measure your pace, your times, and your actual improvements, thinking—and growing as a thinker–isn’t quite as visible. So in college, when you’re told you should likely spend 3 or more hours working outside of class for every hour that a class actually meets, this is when the invisible thinking happens.

Now, rereading an article over and over and never feeling like you’re making progress is a terrible feeling. Much like the pressure or stress of sitting in front of a blank word document and trying to come up with a great opening line. If you aren’t making progress, or don’t feel like you’re making progress, it can be easy to want to give up or just turn in what seems to meet the bare minimum. However, spending time working through difficult texts will actually help you process and understand those texts when you have the right set of tools—questions that help you analyze and take that text apart, for example, will help you make the time you spend on your homework more meaningful and useful!

What does this thinking look like in action? Your teacher is probably going to ask you to reflect, to explain, to analyze multiple different assignments. First, make sure you understand what is being asked of you by these different instructions (reflect – reexamine and reevaluate; explain – take the ideas and concepts and put them in your own words, clarify the ideas, take time to fully process them; analyze – identify different parts of a text, perhaps, and try to understand it more fully by evaluating or processing those different parts). Secondly, set out to meet those instructions fully by working through assignments in steps, using plenty of details and examples to support your ideas and your claims, and writing clearly so your ideas are fully understood by your reader – your teacher or other students.

6. Major Component of College Composition: Sophisticated Use of Sources

In this course, you’ll be working with a variety of sources. Sources come in many forms. Many sources are text based– articles, interviews, and the like–while others rely on visual communication (photos, graphics, etc.). Often, you’ll find that online sources, such as websites, contain a combination of text and images. Expect to encounter sources on a regular basis in your assignments. For example, you might have a homework assignment that asks you to read and respond to an article, or you may be tasked with writing an essay that involves conducting online research.

Things to Remember When You’re Working with Sources

- Consider your intentions. Sometimes, your purpose will be to find sources that support your specific claims and ideas. In these situations, sources should be chosen wisely and with a specific purpose in mind. Knowing why you’re using a source often influences how effectively you can integrate that source into your writing.

- At the same time, be open to a variety of perspectives. When possible, try not to limit yourself to a fixed list of sources, and resist the urge to go hunting only for information that confirms your predetermined ideas. Instead, allow for possibilities that you hadn’t considered, and aim to investigate and articulate your own perspective as you interact with the perspectives of sources.

- Have conversations with your sources. Your relationship with a given source should resemble a dialogue. Don’t just take a source at face value. Rather than positioning your sources as unquestioned authorities, or as backup that “proves” your argument, approach them with a critical eye, ask questions, and comment on what they say, using “I” statements to distinguish your perspective from theirs (yes, you can use “I”!).

- Be a responsible researcher. The sources that you choose should be credible, reliable, and unbiased. You’ll learn more about this as you practice evaluating sources throughout this course.

7. How to Succeed: Metacognition and Meaningful Engagement

Meta, basically, means an awareness of something.

Cognition has to do with thinking and understanding.

So metacognition is an awareness of your own learning, thinking, and comprehension – being metacognitive means you’re being a self-aware student. Teachers assign metacognitive assignments to help students pause and take stock of both their processes and their products, what they’re producing in their classes. These are often reflection assignments, as in: reflect on major concepts from our first unit – what concepts did you learn and which ones were you best able to apply to your own work?

We’ve already talked about how you’ll be engaged in the act of making meaning and contributing to conversations through Critical Inquiry in this course, but you’ll also want to pay attention to yourself—how you’re developing strengths and recognizing weaknesses in your work habits, your writing processes, and in your final products. You’ll reflect metacognitively on your reading and your writing.

Reflecting on your reading will help you determine which strategies are most effective for increasing your reading comprehension. As a successful college reader, you will need to adjust your use of reading strategies depending on the difficulty of the text and your purpose for reading it. Having a toolbox of reading strategies that work well for you will help you successfully monitor your comprehension and troubleshoot problems as they arise. You will want to continue to identify and strengthen the strategies that are working best for you and eliminate the ones that are least effective.

As a writer, reflecting will help you pay attention to your progress, your struggles, your strengths, and your weaknesses. Additionally, by considering different assignments and tasks (in this course and across courses) you will be more likely to transfer your learning and find similarities across assignments that help you to be more prepared and more confident.

Once you start recognizing patterns, hiccups, problems, solutions, and good questions to ask yourself, you’ll be more involved in your learning–and you’ll be better prepared to tackle more challenging assignments. Remember: learning takes time. Everyone has to struggle through difficult tasks. What matters in the end is that we can look back and see how we were able to conquer those challenges–what tools we used and what strategies we employed.

The Right Course for You

HCC offers a variety of paths to help students to master the skills of college composition, including courses that provide extra support while you are enrolled in ENGL-121, and courses designed to support multilingual English learners. If you think that you might benefit from a different kind of pathway or support, communicate with your instructor within the first week of class.

About This Text

This textbook is an Open Educational Resource (OER). OERs are typically authored by several contributors, who have compiled and remixed content from various sources. So, you’ll notice that the chapters and sections in this book often vary by author, style, length, and format. Just like your favorite customized beverage at the local coffee shop, this textbook has been tailored to meet your interests and needs so that you can be successful in College Composition.

Speaking of success…to get the most of this textbook, you are encouraged to be an active reader and thinker. What does it mean to be an active reader? Simply put, an active reader engages, reacts to, and interacts with a text in meaningful ways. While reading, an active reader thinks critically, asks questions, and reacts to what the text says both implicitly and explicitly.

One of the most effective strategies for active reading is to annotate, or mark up the text as you read. Annotating helps you to make important connections that enhance your understanding of the material and help you retain what you have learned. You may already have some familiarity and perhaps even some prior experience with annotation. Highlighting, underlining, and circling key words and phrases, writing notes on the page — if you’ve ever done these things, you’ve annotated a text!

Following are our recommendations for how to annotate this textbook.

If You’d Like to Annotate On Your Screen:

- Using your device, navigate to https://pressbooks.howardcc.edu/criticalreadingcriticalwriting/.

Select “Download this book” and a drop-down menu will appear. The drop-down menu contains a list of format options for downloading the textbook. - From the drop-down menu, select the format option that is best suited for your device. Here are some tips for choosing a suitable format from the drop-down menu:

-

- If you have a computer that contains Adobe Acrobat DC or a similar PDF editing application, select Digital PDF.

- The EPUB and MOBI formats are supported by many devices, including mobile phones, tablets (such as iPad), and eReaders (such as Kindle and Nook). Some devices allow for read-only by default, so you may need to obtain an additional application that will allow you to edit the textbook file.

After you download and open the textbook on your device, use your application’s built-in tools to highlight key content and add your own notes to refer back to later. Tip: In addition to annotating directly on the page, it’s a great idea to jot down notes in a separate notebook or document.

Note: Check with your instructor to see whether they have a preferred annotation method that they recommend. For instance, if your instructor has provided access to a web-based annotation application, such as hypothes.is or NowComment, you can use that application to annotate the textbook directly in your web browser.

If You’d Prefer to Annotate on Paper:

- Using your device, navigate to https://pressbooks.howardcc.edu/criticalreadingcriticalwriting/.

Select “Download this book” and a drop-down menu will appear. The drop-down menu contains a list of format options for downloading the textbook. - From the drop-down menu, select the Print_PDF format option to download the printable textbook. Tip: Before printing, check to be sure that you have enough ink and paper in your printer!

If you don’t have access to a printer, you can order a printed copy of this textbook for a reasonable fee. To do this, navigate to https://pressbooks.howardcc.edu/criticalreadingcriticalwriting/, select the “Buy Book” link, and follow the prompts to purchase a printed copy of the textbook.

CC License

This chapter, “Welcome to College Composition,” by Elizabeth Caruso, Sarah Johnson, and Nicholas Learned, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.