12 Assessment 3.0: The Learning Progression Model

by Elise Naramore

Original blog posting in Reimagined Schools, March 28, 2023

This chapter’s focus is on how to bridge the gap between ungrading and a traditional system. Many people are hesitant to ungrade because it is too mushy or they are simply not allowed. The primary goal of this piece is to explain some necessary structures and some simple steps to take to start the journey.

Are you ready to shift to Assessment 3.0? If you are reading this, then I assume you are seeking the same thing as I am: how to make better humans during the short time you have them in your classroom.

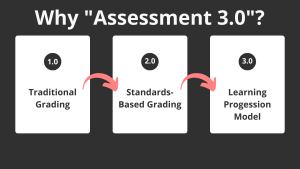

I definitely did NOT find the answer when using traditional grading (Assessment 1.0). I got closer while exploring Standards-Based Grading and its close relations Proficiency-Based Learning and Competency-Based Assessment (let’s call those Assessment 2.0). The good news is that Assessment 3.0, The Learning Progression Model, is a huge step in the right direction. In this article, I want to describe how it came about, some of the research, and how it works. By the end of this article, I hope that you will be eager to begin incorporating its features into your classroom.

My Search for the Answer

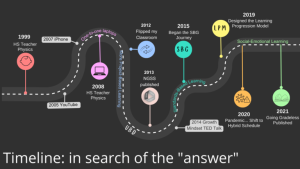

Beginning in 1991 with a job as a part-time teacher of Earth and Physical Science, I have explored many educational trends: multiple intelligences, learning styles, cooperative learning, rubric design, multiple intelligences, authentic assessment, project-based learning, Physics First and more. Then, technology exploded: Google search engine overtook all others; YouTube revolutionized online content; in 2007, the first iPhone was released into the wild.

When I started in my current district in 2008, I continued to investigate each trend with an open mind: embracing one-to-one laptops, using Active Physics, flipping my classroom, planning lessons with Understanding-By-Design (UBD), integrating the Next Generation Science Standards. As I harvested useful techniques, activities, and applications, I folded them into my repository of strategies. But nothing seemed to move my students away from compliance and grade-earning and towards learning meaningful, transferable skills and knowledge.

Assessment 1.0

Up to this point, I was in the phase I call Assessment 1.0. I graded EVERYTHING. I mean everything. I had over 100 grades each marking period: every homework assignment, every quiz, every activity. No joke. It was terrible. And I didn’t know why.

Then my colleague Dave and I started talking. In 2015, he started to experiment with Standards-Based Grading. I joined him in the following semester. Let’s call this Assessment 2.0. Standards-based grading seemed like it was truly the answer to our woes. We would focus on outcomes! We would allow retakes! We would rewrite our rubrics to be about skills, not content!

We did all of that, and… it didn’t work. Standards-Based Grading was a step in the right direction, but failed to solve the fundamental issues of grading. Why?

Standards-Based Grading

First, let me clarify that the term Standards-Based Grading encompasses a wide range of approaches. There is no single approach that fits every situation, just as there is no single approach to anything in education. So, what I’m about to say here is just a generalization. I’ll use a broad brush to capture the most common characteristics of standards-based grading.

Let’s talk about the good things. Standards-based grading aims to address subjective issues like effort, behavior, and attendance that can obscure a student’s true level of understanding. By focusing on specific learning objectives and providing detailed feedback on a student’s progress towards those objectives, it helps students see where they need to improve, which can motivate them to reach higher. This approach emphasizes the skills and knowledge that students should have mastered by the end of a course or grade level.

So, what’s the problem with Standards-Based Grading?

When we put Standards-Based Grading into practice, we experienced several shortcomings of the approach. “A standards-based system can emphasize ‘what’ over ‘how’ so much that important processes, such as reading strategies, writing processes, and problem-solving approaches, get lost in the focus on ‘what’” Brookhart (2013). It is based on the end product or outcome of student learning rather than the process of learning. As a result, it may not be truly equitable for all students, and it is a quantitative evaluation that fails to account for different learning styles and abilities.

Students with learning disabilities or language barriers may struggle to meet the standards set by their grade level, leading to lower grades or even failure. There is no on-ramp with a clear starting point, so they often just give up entirely. Using the number to determine if they were doing well or not, students often miss the point. If the goal is to earn a 4, then students are still focusing on the grade. As noted by Marzano and Heflebower (2012), “While standards-based grading may seem to promote fairness, it can actually be quite unfair to students with different learning needs, leading to lower grades for those who may be making progress but are not yet meeting the same standard as their peers” (p. 24). This approach can also neglect to consider the effort and progress made by a student over time. According to Guskey (2014), “Standards-based grading often ignores the progress students make throughout a grading period and simply reports a final rating of what they have learned. This ignores the important process of learning and often results in grades that don’t accurately reflect what students have learned” (p. 16).

“I can” statements

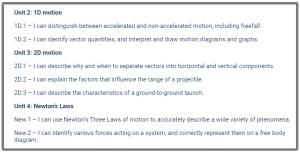

Standards-Based Grade reporting can have a lot more clarity than traditional grading. Instead of lumping all the grades together for one average score, there is often a list of “I can” statements that spell out each item that is being scored. But when I tried this for myself, it was overwhelming to keep track of all of the individual indicators. We did something like this back in 2016-2017, beginning with 38 content standards. Here are a few so you can see some examples.

Plus we added in 9 process standards, 4 math standards, 6 habits of scholarship, 4 presentation standards, and 4 test-taking standards, for a total of 65 standards to track over the course of the year, multiple times. It was staggering. Even when we tried to reduce the number of “I can” statements, we were dissatisfied with the process overall.

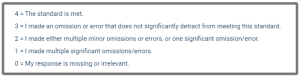

SBG Grading Scales

Standards-Based Grading grading scales are also much better than traditional 0 – 100%, but the lack of clarity and consistency in scoring make it difficult to maintain. While standards can be helpful, the language used in the rubric is crucial in determining the focus of assessment and reporting. A Standards-Based Grading rubric typically uses the same verb but changes how often, how independently, or how well a student does that action to reflect different levels of understanding. The year that we scored each and every one of those 65 standards, we used this quite similar scale:

This can lead to confusion for students and parents as to what they need to do to move to the next level or what specific errors they are making. Moreover, the focus is on what the student is lacking rather than the work produced. It didn’t communicate what students were doing well. This is known as deficit thinking, which undermines the message that we seek to send to all stakeholders. In addition, we quickly recognized that it was difficult for students to understand what “minor” versus “significant” errors are or what “multiple” errors mean, making it unclear and subjective. And this type of scoring was (and is) fairly typical – you can find many similar examples from other teachers and other schools. Yes, it was better, but ultimately undesirable.

Making Changes

Instead of giving up, we continued to modify our process, most of which is outlined in Chapter 4 of “Going Gradeless” (Frangiosa & Naramore, 2021). At the time of publication, we had designed an approach with just 9 practices and no content standards. We had just dumped the numeric scores completely in favor of judgment-free descriptors. And we had begun to use benchmarks to focus students on a particular achievement level in each unit. As we continued to revise throughout 2021 and 2022, we gradually realized that we were no longer DOING Standards-Based Grading. We needed a new name for it, so here is where I formally introduce:

Assessment 3.0: The Learning Progression Model

The Learning Progression Model is a new approach to grading that takes the best aspects of Standards-Based Grading and improves upon them. The Learning Progression Model emphasizes improvement over time, views learning as a process rather than an endpoint, encourages risk-taking, and fosters positive teacher-student relationships. We want to make it clear that we are not trying to disparage Standards-Based Grading; it is a tremendous improvement over traditional grading. We have simply taken the best and most useful aspects of it and brought it to the next level.

Commonalities

One important aspect that the Learning Progression Model and Standards-Based Grading share is the removal of non-academic factors from grading. “Behaviors such as punctuality, attendance, and neatness may be affected by a variety of factors outside the student’s control, such as transportation difficulties or health issues” (AERA, 2002, p. 4). Including these behaviors in assessments can lead to bias and discrimination.

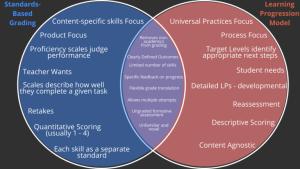

Both the Learning Progression Model and Standards-Based Grading have clearly defined outcomes based on a limited number of skills, with the Learning Progression Model limiting the number even further. Both approaches are designed to provide ample opportunities for formative assessment, allowing students to practice and adjust without penalty. The non-punitive approach encourages students to take risks and try, even when unsure of the outcome. The figure below attempts to summarize the similarities and differences. You can see how much they share.

What makes the LPM Unique

What makes the Learning Progression Model unique is its focus on universal practices that are content-agnostic and spiral through every unit. Multiple attempts are not limited to individual retakes on content-based tests but are instead reassessed throughout the year. We are reassessing everyone, all year long, on the same 10 practices. The Learning Progression Model uses descriptive scoring without numerical values to decrease attempts to quantify performance and instead focuses on what students CAN do, not what they are lacking. It can be easily tailored to whatever group or individual you are working with; this flexibility allows us to use the Learning Progression Model in a wide variety of circumstances and situations. Significantly, it can be scaled to the district or state level.

We designed the Learning Progression model to be a flexible framework designed to recenter learning and meet students at their developmentally-appropriate level. How do we do this? There are six essential components:

- Learning Progressions tied to the practices

- Target Levels

- Assessment

- Ample practice

- A method of reporting progress

- Reflective practice

Let’s take a brief look at each of these separately, why they are important, and how we implement them.

Learning Progressions

First, you need to identify the practices that you are going to use. We have 10, developed from the 8 Science and Engineering Practices (SEPs) from the Next Generation Science Standards. Every discipline has their own state or national standards that outline the desired outcomes for students in their age group, so you can identify your own. We supplemented and reorganized the 8 SEPs to reflect both our values and what we do in our classrooms, as well as to use language easily digested by students and parents.

Each practice is broken down into a Learning Progression. A learning progression is general enough to be used all year long (regardless of the unit), but descriptive enough to provide feedback about what a student CAN do. The achievement levels are developmental; in other words, a student must do the first before it is possible to do the second; they must achieve the first and second in order to do the third, and so on. “Research on instructional design and cognitive psychology has demonstrated that organizing learning into manageable chunks helps to reduce cognitive load and enhance learning outcomes” (Mayer, 2014, p. 8). By breaking down learning into small steps, teachers can help students better manage the cognitive load and improve learning outcomes.

Achievement Levels

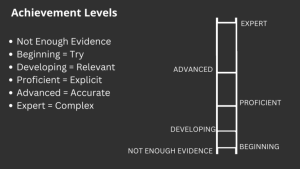

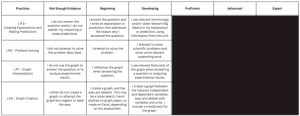

We use six achievement levels, which I envision as a ladder with unequal steps. We have key words to help keep the expectations consistent between different practices, as shown in the figure below.

An Example: “Arguing A Claim”

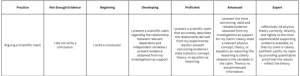

An example will help to clarify things here. Let’s look at something that teachers in many disciplines want their students to be able to do: Arguing a Claim. For my classes, this is present in a lab report, specifically, the conclusion, broken down into the claim, the evidence, and the reasoning. The goal is to communicate the answer to the lab question, the best evidence for that answer, and how those results relate to the known physics theory. The learning progression looks like this:

The progression starts with Beginning, where the student tries to write a conclusion, and then moves to Developing, where they write a scientific claim and provide some evidence, followed by Proficient, where they write the correct claim and provide convincing evidence, and then Advanced, where they are persuasive, correct, and focused, and finally Expert, where they pull in some of the Advanced analysis to more fully persuade the reader about the validity of the claim. Each level describes what students CAN do.

The goal of this progression is to build up gradually, with each step building on the previous one, to develop the student’s ability to write a convincing and accurate scientific claim, supported by relevant evidence and reasoning. The specific content is left to the assessment itself, but the skills developed through this progression can be applied to any subject or discipline where students are required to argue a claim based on evidence and reasoning.

Target Levels

One of the most important changes we made in the transition from Standards-Based Grading to the Learning Progression Model was focusing on Target Levels which are specific benchmarks that students are expected to reach by the end of a unit. By breaking down learning into small steps that are developmentally appropriate, we can help reduce cognitive load and support the development of executive function skills, such as working memory, attention, and self-regulation (Sweller et al., 2011, p. 2). Giving students one step at a time to master and assimilate helps reduce the cognitive load and makes learning more effective. These targets help students and teachers identify where students are in their learning journey and provide actionable feedback to move students towards their goal.

How do I decide on the target levels for a particular course?

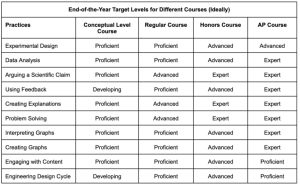

At the beginning of the year, I have a plan of where I want to get to… mostly based upon previous years’ results, but also based upon my expectations of what distinguishes Conceptual level from regular from Honors from Advanced Placement. For example, we expect that students in an AP course can work independently, at a faster pace, and integrate multiple concepts and strategies for answering questions and solving problems. The test emphasizes a sophisticated and complex understanding of concepts and skills; that’s what these students are signing up for!

While philosophically I believe that all students can do AP level work if given enough time and support, the fact remains that we have limited time and limited support. Therefore, not all students will have the motivation and desire to take this level of class. This explains why my targets by the end of the year for AP would be mostly at the Expert level. For Honors students, Advanced level would be appropriate, since we don’t move at a pace allowing them to practice the complex and sophisticated integration of concepts. For regular class, they should earn mostly proficient; Conceptual Physics a mixture of proficient and developing.

So, those are my expectations.

How do I adjust based upon the real students that are in front of me?

We adjust our targets based on their performance on assessments. For example, if students in my current physics course overwhelmingly earn a Developing level instead of the targeted Proficient level, I will maintain the Proficient as the target for the next unit, regardless of my earlier plans. We also coach students individually to take next steps, even if the next level is masked.

As the year progresses, students will differentiate more and more, some backsliding, some maintaining, and some surging ahead. Target levels help students and teachers identify where students are in their learning journey, provide actionable feedback to move students towards their goal, and provide ample practice along the way. And this, my friends, is the whole point of assessment.

Assessments

“Assessment should not be separate from teaching. It should be an integral part of teaching, providing evidence of what is and isn’t working.”

Dylan Wiliam, 2011

Assessment is a crucial part of teaching, and there are various types of assessments that you can use in your classroom, such as labs, checkpoints, projects, essays, research papers, tests, presentations, listening comprehension, and many others. I have simplified the types of assessments to maximize feedback in the 10 practices. Using only lab reports, checkpoints (tests and quizzes), and projects, I can accurately gauge growth. Each type of assessment generally provides a check on the same practices each time. For example, on checkpoints, there is always going to be one question each for Creating Explanations, Problem Solving, Interpreting Graphs and Creating Graphs.

However, I CAN bring in other skills. While I am going to generally focus on a few things at a time and in very specific contexts, occasionally I do add other practices, such as experimental design or using feedback. This helps students know what to expect and feel more comfortable. It also streamlines the feedback process for me! When each type assessment is associated with its own specific practices, you can focus your feedback.

Masking Target Levels

As discussed earlier, throughout the year, the target levels for assessments will change. When I put a rubric on a test, I only expose the rubric up to the current target levels. Because it isn’t usually an option to look ahead, they stay focused on just meeting the target level. That’s the goal. Stick with me. Meet the targets as I define them. For example, at the end of Unit 2, the rubric may have the target levels set at Developing for all four practices.

As students begin to differentiate, some may plateau while others may be eager to forge ahead. I can discuss next steps with those who are ready to move on to the higher achievement levels. As a critical mass reaches the target, I then expose the next target level for all.

Assessment + Feedback

However, assessment alone is not enough. Feedback is essential for learning to take place. Without feedback, students may simply look at their assessment results and file them away without learning from their mistakes.

“Effective feedback is essential to learning. Feedback should be timely, specific, and focused on the task or process, not the person. Feedback should also provide suggestions for improvement and be oriented towards achieving goals”

Hattie & Timperley, 2007

To promote learning, students need to ask themselves questions such as “What did I do?”, “Did it work?”, and “What can I do to make it better next time?” Then, they need to be given a chance to apply what they’ve learned and try again.

Ample Practice

To practice is different from a Practice. Our ten Practices describe what students can do as a result of learning. Practicing is when one performs (an activity) or exercises (a skill) repeatedly or regularly in order to improve or maintain one’s proficiency. Practice is crucial in the classroom setting, where every activity offers an opportunity to work on the learning progression at the targeted level. With the Learning Progression Model, everything that students do is practice, whether it is “graded” or not.

Practice is the primary means of identifying where students stand in their learning journey and providing them with actionable feedback. Sports serve as a useful analogy to learning and assessment in the classroom. “Just like sports, learning requires practice and repetition to build mastery” (The Learning Agency, 2020). Like athletes, students must practice their skills and strategies repeatedly in a controlled environment to build mastery and confidence.

As students progress, they move on to formative assessments, which are similar to scrimmages in sports. “Formative assessment provides an opportunity for students to receive feedback on their learning progress before the high-stakes game (summative assessment)” (Panadero & Jonsson, 2013). It allows students to learn from their mistakes and identify areas that require more practice or support. In higher-stakes assessments, students apply their learning in a more demanding environment. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that the test is not the end goal, but rather an opportunity to identify areas of strength and weakness.

Assessment + Feedback + Practice

We had said earlier that assessment and feedback are intertwined. Now we throw practice into the mix. Single skill practice may create a false impression of mastery. “Interleaving practice, or mixing up different skills or concepts during practice, can enhance long-term retention and transfer of learning” (Rohrer & Taylor, 2007). Cycling back to focus on specific skills or concepts that need more work and then practicing them until they can be integrated into the overall understanding is essential. Practice that takes the same form as tests, with multiple types of questions and problems, is crucial for the long-term development of skills.

Reporting Progress

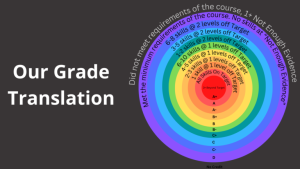

Ideally, we would not have to give grades at all, an assessment approach called UNgrading. But, since we all mostly work in institutions that require grades, how do we fit the Learning Progression Model into a traditional grades school?

Our solution: we tie the target levels to the grade translations. In a nutshell, an A always means “meets all target levels”, no matter what those targets are. If students are 1 level below target, that puts them in a B range depending on how many practices; if they are 2 levels below target, that puts them in a C range. (This is a significant update from what we described in Chapter 7 of Going Gradeless.) This means that we can use the same grade translation for every course, throughout the entire year. Because we have the flexibility of adapting the target levels, as described above, we can meet the needs of any class, any course, any individual, without altering the grade translation chart itself.

One other benefit is the focus on growth. We don’t need all students to be experts in our subject matter. What we want is for them to engage in learning, to focus on improving incrementally over time. Perfect is not what we need. Active, invested participation is. By tying the grade to the target levels, we focus attention on the skills students need to master and what steps they need to take to get there.

Reflective Practice

That brings us to the last essential component of the Learning Progression Model, reflection. When students engage in reflection, they are encouraged to think about their own thinking and learning, which can help them develop metacognitive skills.

“Without reflection, students may not have a clear understanding of what they have learned or how they can improve. Reflection can help students to identify their strengths and weaknesses, set goals, and develop strategies for future learning”

Stommel, 2020

Students often have no idea why they are doing what they are doing nor why (or even if) it is working. If we want students to have agency, then we need to provide time for reflective thought. This is an area that I overlooked for most of my teaching career, even though I knew it was important for myself.

Types of Reflection

Reflection can take many forms: conferencing, journaling, test corrections, goal setting… and each of these can be formal or informal. I personally use 4 different strategies in my classroom:

- “Using Feedback” mostly on lab reports. This is one of my Practices, developed to formally teach students how to read my descriptive feedback, take action on that feedback, and communicate what they have learned from going through that process.

- Three annual one-on-one conferences. During these 5 -10 minute meetings, I ask (and answer) questions, hear the student’s concerns, discuss current progress and what I can do to support his/her goals.

- Goal setting. At the end of each unit, students document their current progress and use the grade translation chart to figure out their current grade. They state whether or not they are on track to meet their own professed goals, and if not, what they need to do to get there.

- Writing: Occasionally, I will have students informally journal, especially if I notice a general pattern of disengagement or passivity. I have had them send emails requesting support from me, their guidance counselor, and/or their parents. At times, they write a more comprehensive narrative, critiquing their current performance.

All of this takes time, but honestly, it is time well-spent. It shifts the power from you to them, as they see the choices they are making influence the results that they are achieving. Engaging in reflection can help students to identify their strengths and weaknesses, adapt their study strategies to better meet their own needs, and promote a growth mindset. It is not meant to assign blame, but to encourage students to grab the reins and take charge!

Ready to Explore the Learning Progression Method?

Excitement about the possibilities that the Learning Progression Model opens up for you can be tempered by fear and an overwhelming sense of “Oh no, I have to redo everything in my entire curriculum!” This is absolutely not true! Several small shifts can be implemented immediately. More significant shifts can occur later, but even then, we never altered our fundamental curriculum. The activities, assignments and assessments do not have to change; how you use them will. So what can you do right now?

Four things you can do right now

1. Change the language used when talking or thinking about students.

When we use labels to describe students, we can unintentionally limit our expectations of them. This can create pressure and anxiety for students, whether they typically earn high or low grades. In fact, students who are labeled as high achievers can experience pressure to maintain that label, leading to anxiety and fear of failure (Schussler, 2020). What do labels sound like?

- She’s an “A-student”

- He’s a “Special Ed Student”

- She’s a “Trouble Maker”

- He’s not a “math-person”

Because “labels are judgments, not facts” (Dweck, 2017), it is important for teachers to avoid labeling students and instead focus on their strengths and potential for growth. It’s a simple matter of choosing our words wisely. For example: Instead of “She’s an A-student”, we can say “a student who is demonstrating success” or “a student who is currently earning an A.” Instead of “He’s a Special Ed Student”, we can say “a student who has an IEP’.

We are not merely trying to be politically correct here. This is a matter of opening up our minds to see people as more three dimensional, with characteristics beyond this one attribute. By reframing our language and avoiding labels, we can create a more positive and inclusive learning environment for all students.

2. Engage in constant, transparent communication.

If I want students to have agency, then I have to explain why I am asking them to engage in the activities in a particular way. According to a study by Anderman and Anderman (2018), when teachers communicate the purpose of feedback, provide students with clear and specific criteria for success, and involve them in the feedback process, students are more likely to engage with and use feedback to improve their learning (p. 67). When students understand the purpose of assessments and how they can use feedback to improve, they are more likely to engage in the learning process.

Explain why you are doing each activity or lesson. Not just the essential question, or course objectives, but what you hope they will get as a result of doing it in this particular manner. I tell the students overtly that I want them to understand my rationale, that I don’t do anything to fill time, and that I want to know what is (or is not) useful. Taking the time to explain my thinking helps to model clear communication, respects their role as recipients of my plans, and hopefully, points them in my intended direction. They know why I am assigning X, so hopefully they will seek that result.

3. Use a Feedback Rubric.

It may seem odd to use a rubric to provide feedback on how well students are using feedback. But this approach can provide a structure for students to engage with teacher feedback and reflect on their learning. Incorporating feedback rubrics into assessments can encourage students to reflect on their learning and take ownership of their progress (Black & Wiliam, 2018). When students are given specific feedback on their work and encouraged to respond to it, they can develop metacognitive skills and a growth mindset.

4. Make Time for Reflective Practices.

Reflective practices, such as journaling or conferencing, can help students develop metacognitive skills and become more self-aware learners. By incorporating reflective practices into your assessment strategies, you can help students develop a deeper understanding of their own learning and become more effective learners. I believe that the incorporation of reflective practices into my classroom has made the greatest impact on my relationship with my students overall.

I have many resources to support your journey, no matter what path you choose. Please explore our resources page and professional development courses. If you cannot find what you need, please reach out to me using any of my contact information. I am happy to collaborate or debate alternate approaches.

Conclusion

Assessment 3.0, the Learning Progression model, offers a significant improvement over traditional grading and Standards-Based Grading. It’s not perfect, especially when you are the only teacher in your students’ day that uses this approach. I struggle to get students to accept the power that I am offering.

But, by focusing on improvement over time, emphasizing learning as a process, and fostering positive teacher-student relationships, this model ensures that students receive meaningful feedback that helps them grow and succeed. Moreover, by removing non-academic factors from grading, this model promotes fairness and equity, helping students from all backgrounds reach their full potential. Finally, by encouraging reflective practice, the Learning Progression Model promotes a growth mindset that will serve students well throughout their lives. It is a realistic step towards ditching grades altogether, taking all the positives from the UNgrading approach while acknowledging the reality that most of us live in.

I am putting The Learning Progression Model out in the hopes that you will help me forge a path forward. If I can be of any assistance to you, please feel free to contact me using my contact information at the top of this page or through my social media. I look forward to continuing the conversation and pushing the boundaries of what is possible together.

References

American Educational Research Association. (2002). Knowing what students know: The science and design of educational assessment. National Academy Press.

Anderman, E. M., & Anderman, L. H. (2018). Classroom motivation: Theory, research, and practice. Routledge.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7-74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102

Brookhart, S. M. (2013). The case against percentage grades. Educational Leadership, 70(1), 38-43.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Hyler, M. E. (2020). Teacher reflection in a time of crisis. Educational Leadership, 77(2), 6-11.

Duke Learning Innovation. (n.d.). Practice and Feedback. https://learninginnovation.duke.edu/resources/guides/practice-and-feedback/

Frangiosa, D. & Naramore, E. (2021). Going Gradeless: Shifting the Focus to Student Learning. Corwin Press.

Guskey, T. R. (2014). On your mark: Challenging the conventions of grading and reporting. Solution Tree Press.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112.

Marzano, R. J., & Heflebower, T. (2012). The critical role of grading in teaching and learning. Educational Leadership, 69(3), 78-80.

Mayer, R. E. (2014). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning. In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (pp. 43-71). Cambridge University Press.

Panadero, E., & Jonsson, A. (2013). The Use of Formative Assessment in the Classroom for Learning Purposes. In S. M. Downing & T. L. Haladyna (Eds.), Handbook of Test Development (pp. 357-386). Routledge.

Rohrer, D., & Taylor, K. (2007). The Effects of Overlearning and Distributed Practice on the Retention of Mathematics Knowledge. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21(1), 139-156.

Schussler, D. L. (2020). High achieving students and the pressure to succeed. Journal of Advanced Academics, 31(1), 64-83. doi: 10.1177/1932202X19892606

“Science And Engineering Practices (SEP) | Next Generation Science Standards”. Nextgenscience.Org, 2023, https://www.nextgenscience.org/glossary/science-and-engineering-practices-sep. Accessed 17 Mar 2023.

Stommel, J. (2020). Why Ungrading Is Essential for Equity-Centered Pedagogy. EdSurge. Retrieved from https://www.edsurge.com/news/2020-11-12-why-ungrading-is-essential-for-equity-centered-pedagogy.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Springer.

The Learning Agency. (2020). Practice: The Neuroscience of Improvement. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f2O6mQkFiiw

Wiliam, D. (2011). What is assessment for learning? Studies in Educational Evaluation, 37(1), 3-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.03.001