8 2.3 Explaining Poverty

Learning Objectives

- Describe the assumptions of the functionalist and conflict views of stratification and of poverty.

- Explain the focus of symbolic interactionist work on poverty.

- Understand the difference between the individualist and structural explanations of poverty.

Why does poverty exist, and why and how do poor people end up being poor? The sociological perspectives introduced in Chapter 1 “Understanding Social Problems” provide some possible answers to these questions through their attempt to explain why American society is stratified—that is, why it has a range of wealth ranging from the extremely wealthy to the extremely poor. We review what these perspectives say generally about social stratification (rankings of people based on wealth and other resources a society values) before turning to explanations focusing specifically on poverty.

In general, the functionalist perspective and conflict perspective both try to explain why social stratification exists and endures, while the symbolic interactionist perspective discusses the differences that stratification produces for everyday interaction. Table 2.2 “Theory Snapshot” summarizes these three approaches.

Table 2.2 Theory Snapshot

| Theoretical perspective | Major assumptions |

|---|---|

| Functionalism | Stratification is necessary to induce people with special intelligence, knowledge, and skills to enter the most important occupations. For this reason, stratification is necessary and inevitable. |

| Conflict theory | Stratification results from lack of opportunity and from discrimination and prejudice against the poor, women, and people of color. It is neither necessary nor inevitable. |

| Symbolic interactionism | Stratification affects people’s beliefs, lifestyles, daily interaction, and conceptions of themselves. |

The Functionalist View

As discussed in Chapter 1 “Understanding Social Problems”, functionalist theory assumes that society’s structures and processes exist because they serve important functions for society’s stability and continuity. In line with this view, functionalist theorists in sociology assume that stratification exists because it also serves important functions for society. This explanation was developed more than sixty years ago by Kingsley Davis and Wilbert Moore (Davis & Moore, 1945) in the form of several logical assumptions that imply stratification is both necessary and inevitable. When applied to American society, their assumptions would be as follows:

- Some jobs are more important than other jobs. For example, the job of a brain surgeon is more important than the job of shoe shining.

- Some jobs require more skills and knowledge than other jobs. To stay with our example, it takes more skills and knowledge to perform brain surgery than to shine shoes.

- Relatively few people have the ability to acquire the skills and knowledge that are needed to do these important, highly skilled jobs. Most of us would be able to do a decent job of shining shoes, but very few of us would be able to become brain surgeons.

- To encourage the people with the skills and knowledge to do the important, highly skilled jobs, society must promise them higher incomes or other rewards. If this is true, some people automatically end up higher in society’s ranking system than others, and stratification is thus necessary and inevitable.

To illustrate their assumptions, say we have a society where shining shoes and doing brain surgery both give us incomes of $150,000 per year. (This example is very hypothetical, but please keep reading.) If you decide to shine shoes, you can begin making this money at age 16, but if you decide to become a brain surgeon, you will not start making this same amount until about age 35, as you must first go to college and medical school and then acquire several more years of medical training. While you have spent nineteen additional years beyond age 16 getting this education and training and taking out tens of thousands of dollars in student loans, you could have spent those years shining shoes and making $150,000 a year, or $2.85 million overall. Which job would you choose?

Functional theory argues that the promise of very high incomes is necessary to encourage talented people to pursue important careers such as surgery. If physicians and shoe shiners made the same high income, would enough people decide to become physicians?

Public Domain Images – CC0 public domain.

As this example suggests, many people might not choose to become brain surgeons unless considerable financial and other rewards awaited them. By extension, we might not have enough people filling society’s important jobs unless they know they will be similarly rewarded. If this is true, we must have stratification. And if we must have stratification, then that means some people will have much less money than other people. If stratification is inevitable, then, poverty is also inevitable. The functionalist view further implies that if people are poor, it is because they do not have the ability to acquire the skills and knowledge necessary for the important, high-paying jobs.

The functionalist view sounds very logical, but a few years after Davis and Moore published their theory, other sociologists pointed out some serious problems in their argument (Tumin, 1953; Wrong, 1959).

First, it is difficult to compare the importance of many types of jobs. For example, which is more important, doing brain surgery or mining coal? Although you might be tempted to answer with brain surgery, if no coal were mined then much of our society could not function. In another example, which job is more important, attorney or professor? (Be careful how you answer this one!)

Second, the functionalist explanation implies that the most important jobs have the highest incomes and the least important jobs the lowest incomes, but many examples, including the ones just mentioned, counter this view. Coal miners make much less money than physicians, and professors, for better or worse, earn much less on the average than lawyers. A professional athlete making millions of dollars a year earns many times the income of the president of the United States, but who is more important to the nation? Elementary school teachers do a very important job in our society, but their salaries are much lower than those of sports agents, advertising executives, and many other people whose jobs are far less essential.

Third, the functionalist view assumes that people move up the economic ladder based on their abilities, skills, knowledge, and, more generally, their merit. This implies that if they do not move up the ladder, they lack the necessary merit. However, this view ignores the fact that much of our stratification stems from lack of equal opportunity. As later chapters in this book discuss, because of their race, ethnicity, gender, and class standing at birth, some people have less opportunity than others to acquire the skills and training they need to fill the types of jobs addressed by the functionalist approach.

Finally, the functionalist explanation might make sense up to a point, but it does not justify the extremes of wealth and poverty found in the United States and other nations. Even if we do have to promise higher incomes to get enough people to become physicians, does that mean we also need the amount of poverty we have? Do CEOs of corporations really need to make millions of dollars per year to get enough qualified people to become CEOs? Do people take on a position as CEO or other high-paying job at least partly because of the challenge, working conditions, and other positive aspects they offer? The functionalist view does not answer these questions adequately.

One other line of functionalist thinking focuses more directly on poverty than generally on stratification. This particular functionalist view provocatively argues that poverty exists because it serves certain positive functions for our society. These functions include the following: (1) poor people do the work that other people do not want to do; (2) the programs that help poor people provide a lot of jobs for the people employed by the programs; (3) the poor purchase goods, such as day-old bread and used clothing, that other people do not wish to purchase, and thus extend the economic value of these goods; and (4) the poor provide jobs for doctors, lawyers, teachers, and other professionals who may not be competent enough to be employed in positions catering to wealthier patients, clients, students, and so forth (Gans, 1972). Because poverty serves all these functions and more, according to this argument, the middle and upper classes have a vested interested in neglecting poverty to help ensure its continued existence.

The Conflict View

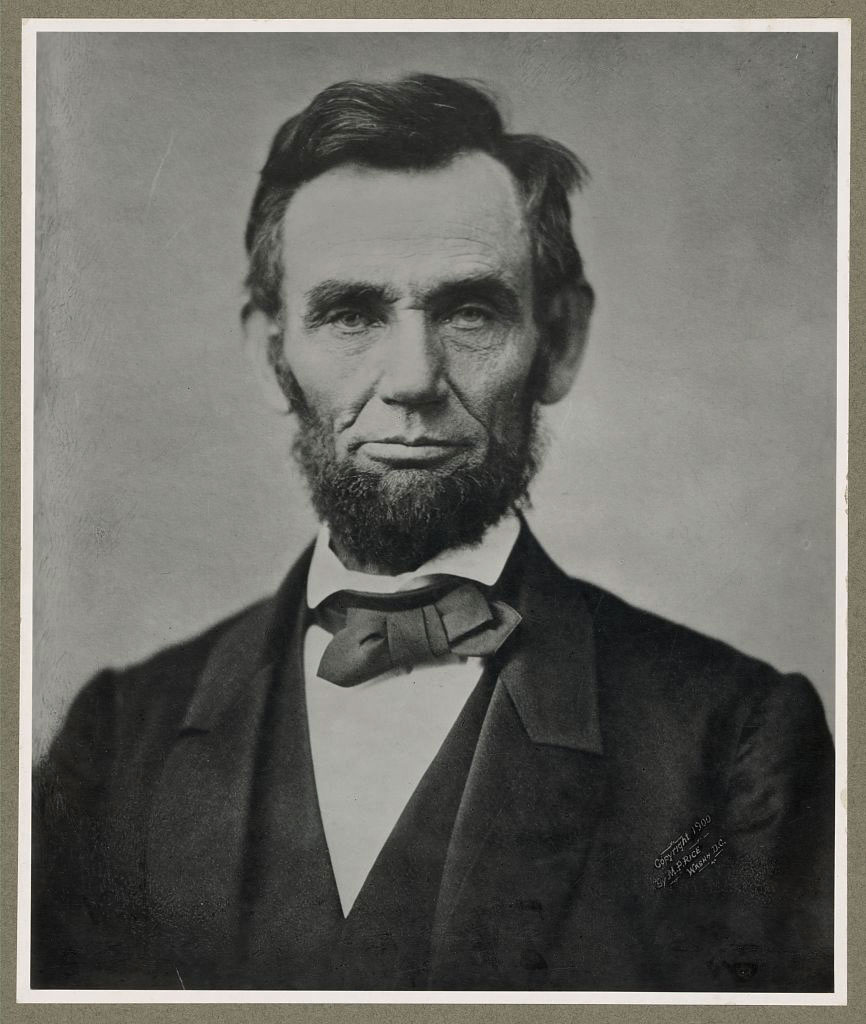

Because he was born in a log cabin and later became president, Abraham Lincoln’s life epitomizes the American Dream, which is the belief that people born into poverty can become successful through hard work. The popularity of this belief leads many Americans to blame poor people for their poverty.

US Library of Congress – public domain.

Conflict theory’s explanation of stratification draws on Karl Marx’s view of class societies and incorporates the critique of the functionalist view just discussed. Many different explanations grounded in conflict theory exist, but they all assume that stratification stems from a fundamental conflict between the needs and interests of the powerful, or “haves,” in society and those of the weak, or “have-nots” (Kerbo, 2012). The former take advantage of their position at the top of society to stay at the top, even if it means oppressing those at the bottom. At a minimum, they can heavily influence the law, the media, and other institutions in a way that maintains society’s class structure.

In general, conflict theory attributes stratification and thus poverty to lack of opportunity from discrimination and prejudice against the poor, women, and people of color. In this regard, it reflects one of the early critiques of the functionalist view that the previous section outlined. To reiterate an earlier point, several of the remaining chapters of this book discuss the various obstacles that make it difficult for the poor, women, and people of color in the United States to move up the socioeconomic ladder and to otherwise enjoy healthy and productive lives.

Symbolic Interactionism

Consistent with its micro orientation, symbolic interactionism tries to understand stratification and thus poverty by looking at people’s interaction and understandings in their daily lives. Unlike the functionalist and conflict views, it does not try to explain why we have stratification in the first place. Rather, it examines the differences that stratification makes for people’s lifestyles and their interaction with other people.

Many detailed, insightful sociological books on the lives of the urban and rural poor reflect the symbolic interactionist perspective (Anderson, 1999; C. M. Duncan, 2000; Liebow, 1993; Rank, 1994). These books focus on different people in different places, but they all make very clear that the poor often lead lives of quiet desperation and must find ways of coping with the fact of being poor. In these books, the consequences of poverty discussed later in this chapter acquire a human face, and readers learn in great detail what it is like to live in poverty on a daily basis.

Some classic journalistic accounts by authors not trained in the social sciences also present eloquent descriptions of poor people’s lives (Bagdikian, 1964; Harrington, 1962). Writing in this tradition, a newspaper columnist who grew up in poverty recently recalled, “I know the feel of thick calluses on the bottom of shoeless feet. I know the bite of the cold breeze that slithers through a drafty house. I know the weight of constant worry over not having enough to fill a belly or fight an illness…Poverty is brutal, consuming and unforgiving. It strikes at the soul” (Blow, 2011).

Sociological accounts of the poor provide a vivid portrait of what it is like to live in poverty on a daily basis.

Pixabay – CC0 public domain.

On a more lighthearted note, examples of the symbolic interactionist framework are also seen in the many literary works and films that portray the difficulties that the rich and poor have in interacting on the relatively few occasions when they do interact. For example, in the film Pretty Woman, Richard Gere plays a rich businessman who hires a prostitute, played by Julia Roberts, to accompany him to swank parties and other affairs. Roberts has to buy a new wardrobe and learn how to dine and behave in these social settings, and much of the film’s humor and poignancy come from her awkwardness in learning the lifestyle of the rich.

Specific Explanations of Poverty

The functionalist and conflict views focus broadly on social stratification but only indirectly on poverty. When poverty finally attracted national attention during the 1960s, scholars began to try specifically to understand why poor people become poor and remain poor. Two competing explanations developed, with the basic debate turning on whether poverty arises from problems either within the poor themselves or in the society in which they live (Rank, 2011). The first type of explanation follows logically from the functional theory of stratification and may be considered an individualistic explanation. The second type of explanation follows from conflict theory and is a structural explanation that focuses on problems in American society that produce poverty. Table 2.3 “Explanations of Poverty” summarizes these explanations.

Table 2.3 Explanations of Poverty

| Explanation | Major assumptions |

|---|---|

| Individualistic | Poverty results from the fact that poor people lack the motivation to work and have certain beliefs and values that contribute to their poverty. |

| Structural | Poverty results from problems in society that lead to a lack of opportunity and a lack of jobs. |

It is critical to determine which explanation makes more sense because, as sociologist Theresa C. Davidson (Davidson, 2009) observes, “beliefs about the causes of poverty shape attitudes toward the poor.” To be more precise, the particular explanation that people favor affects their view of government efforts to help the poor. Those who attribute poverty to problems in the larger society are much more likely than those who attribute it to deficiencies among the poor to believe that the government should do more to help the poor (Bradley & Cole, 2002). The explanation for poverty we favor presumably affects the amount of sympathy we have for the poor, and our sympathy, or lack of sympathy, in turn affects our views about the government’s role in helping the poor. With this backdrop in mind, what do the individualistic and structural explanations of poverty say?

Individualistic Explanation

According to the individualistic explanation, the poor have personal problems and deficiencies that are responsible for their poverty. In the past, the poor were thought to be biologically inferior, a view that has not entirely faded, but today the much more common belief is that they lack the ambition and motivation to work hard and to achieve success. According to survey evidence, the majority of Americans share this belief (Davidson, 2009). A more sophisticated version of this type of explanation is called the culture of poverty theory (Banfield, 1974; Lewis, 1966; Murray, 2012). According to this theory, the poor generally have beliefs and values that differ from those of the nonpoor and that doom them to continued poverty. For example, they are said to be impulsive and to live for the present rather than the future.

Regardless of which version one might hold, the individualistic explanation is a blaming-the-victim approach (see Chapter 1 “Understanding Social Problems”). Critics say this explanation ignores discrimination and other problems in American society and exaggerates the degree to which the poor and nonpoor do in fact hold different values (Ehrenreich, 2012; Holland, 2011; Schmidt, 2012). Regarding the latter point, they note that poor employed adults work more hours per week than wealthier adults and that poor parents interviewed in surveys value education for their children at least as much as wealthier parents. These and other similarities in values and beliefs lead critics of the individualistic explanation to conclude that poor people’s poverty cannot reasonably be said to result from a culture of poverty.

Structural Explanation

According to the second, structural explanation, which is a blaming-the-system approach, US poverty stems from problems in American society that lead to a lack of equal opportunity and a lack of jobs. These problems include (a) racial, ethnic, gender, and age discrimination; (b) lack of good schooling and adequate health care; and (c) structural changes in the American economic system, such as the departure of manufacturing companies from American cities in the 1980s and 1990s that led to the loss of thousands of jobs. These problems help create a vicious cycle of poverty in which children of the poor are often fated to end up in poverty or near poverty themselves as adults.

As Rank (Rank, 2011) summarizes this view, “American poverty is largely the result of failings at the economic and political levels, rather than at the individual level…In contrast to [the individualistic] perspective, the basic problem lies in a shortage of viable opportunities for all Americans.” Rank points out that the US economy during the past few decades has created more low-paying and part-time jobs and jobs without benefits, meaning that Americans increasingly find themselves in jobs that barely lift them out of poverty, if at all. Sociologist Fred Block and colleagues share this critique of the individualistic perspective: “Most of our policies incorrectly assume that people can avoid or overcome poverty through hard work alone. Yet this assumption ignores the realities of our failing urban schools, increasing employment insecurities, and the lack of affordable housing, health care, and child care. It ignores the fact that the American Dream is rapidly becoming unattainable for an increasing number of Americans, whether employed or not” (Block, et. al., 2006).

Most sociologists favor the structural explanation. As later chapters in this book document, racial and ethnic discrimination, lack of adequate schooling and health care, and other problems make it difficult to rise out of poverty. On the other hand, some ethnographic research supports the individualistic explanation by showing that the poor do have certain values and follow certain practices that augment their plight (Small, et. al., 2010). For example, the poor have higher rates of cigarette smoking (34 percent of people with annual incomes between $6,000 and $11,999 smoke, compared to only 13 percent of those with incomes $90,000 or greater [Goszkowski, 2008]), which helps cause them to have more serious health problems.

Adopting an integrated perspective, some researchers say these values and practices are ultimately the result of poverty itself (Small et, al., 2010). These scholars concede a culture of poverty does exist, but they also say it exists because it helps the poor cope daily with the structural effects of being poor. If these effects lead to a culture of poverty, they add, poverty then becomes self-perpetuating. If poverty is both cultural and structural in origin, these scholars say, efforts to improve the lives of people in the “other America” must involve increased structural opportunities for the poor and changes in some of their values and practices.

Key Takeaways

- According to the functionalist view, stratification is a necessary and inevitable consequence of the need to use the promise of financial reward to encourage talented people to pursue important jobs and careers.

- According to conflict theory, stratification results from lack of opportunity and discrimination against the poor and people of color.

- According to symbolic interactionism, social class affects how people interact in everyday life and how they view certain aspects of the social world.

- The individualistic view attributes poverty to individual failings of poor people themselves, while the structural view attributes poverty to problems in the larger society.

For Your Review

- In explaining poverty in the United States, which view, individualist or structural, makes more sense to you? Why?

- Suppose you could wave a magic wand and invent a society where everyone had about the same income no matter which job he or she performed. Do you think it would be difficult to persuade enough people to become physicians or to pursue other important careers? Explain your answer.

References

Anderson, E. (1999). Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Bagdikian, B. H. (1964). In the midst of plenty: The poor in America. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Banfield, E. C. (1974). The unheavenly city revisited. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

Block, F., Korteweg, A. C., & Woodward, K. (2006). The compassion gap in American poverty policy. Contexts, 5(2), 14–20.

Blow, C. M. (2011, June 25). Them that’s not shall lose. New York Times, p. A19.

Bradley, C., & Cole, D. J. (2002). Causal attributions and the significance of self-efficacy in predicting solutions to poverty. Sociological Focus, 35, 381–396.

Davidson, T. C. (2009). Attributions for poverty among college students: The impact of service-learning and religiosity. College Student Journal, 43, 136–144.

Davis, K., & Moore, W. (1945). Some principles of stratification. American Sociological Review, 10, 242–249.

Duncan, C. M. (2000). Worlds apart: Why poverty persists in rural America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Ehrenreich, B. (2012, March 15). What “other America”? Salon.com. Retrieved from http://www.salon.com/2012/03/15/the_truth_about_the_poor/.

Gans, H. J. (1972). The positive functions of poverty. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 275–289.

Goszkowski, R. (2008). Among Americans, smoking decreases as income increases. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/105550/among-americans-smoking-decreases-income-increases.aspx.

Harrington, M. (1962). The other America: Poverty in the United States. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Holland, J. (2011, July 29). Debunking the big lie right-wingers use to justify black poverty and unemployment. AlterNet. Retrieved from http://www.alternet.org/story/151830/debunking_the_big_lie_right-wingers_use_to_justify_black_poverty _and_unemployment_?page=entire.

Kerbo, H. R. (2012). Social stratification and inequality. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Lewis, O. (1966). The culture of poverty. Scientific American, 113, 19–25.

Liebow, E. (1993). Tell them who I am: The lives of homeless women. New York, NY: Free Press.

Murray, C. (2012). Coming apart: The state of white America, 1960–2010. New York, NY: Crown Forum.

Rank, M. R. (1994). Living on the edge: The realities of welfare in America. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Rank, M. R. (2011). Rethinking American poverty. Contexts, 10(Spring), 16–21.

Schmidt, P. (2012, February 12). Charles Murray, author of the “Bell Curve,” steps back into the ring. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/Charles-Murray-Author-of-The/130722/?sid=at&utm_source=at&utm_medium=en.

Small, M. L., Harding, D. J., & Lamont, M. (2010). Reconsidering culture and poverty. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 629(May), 6–27.

Tumin, M. M. (1953). Some principles of stratification: A critical analysis. American Sociological Review, 18, 387–393.

Wrong, D. H. (1959). The functional theory of stratification: Some neglected considerations. American Sociological Review, 24, 772–782.