14 The Rhetorical Situation

- Profile

- What Others Say About the Rhetorical Situation

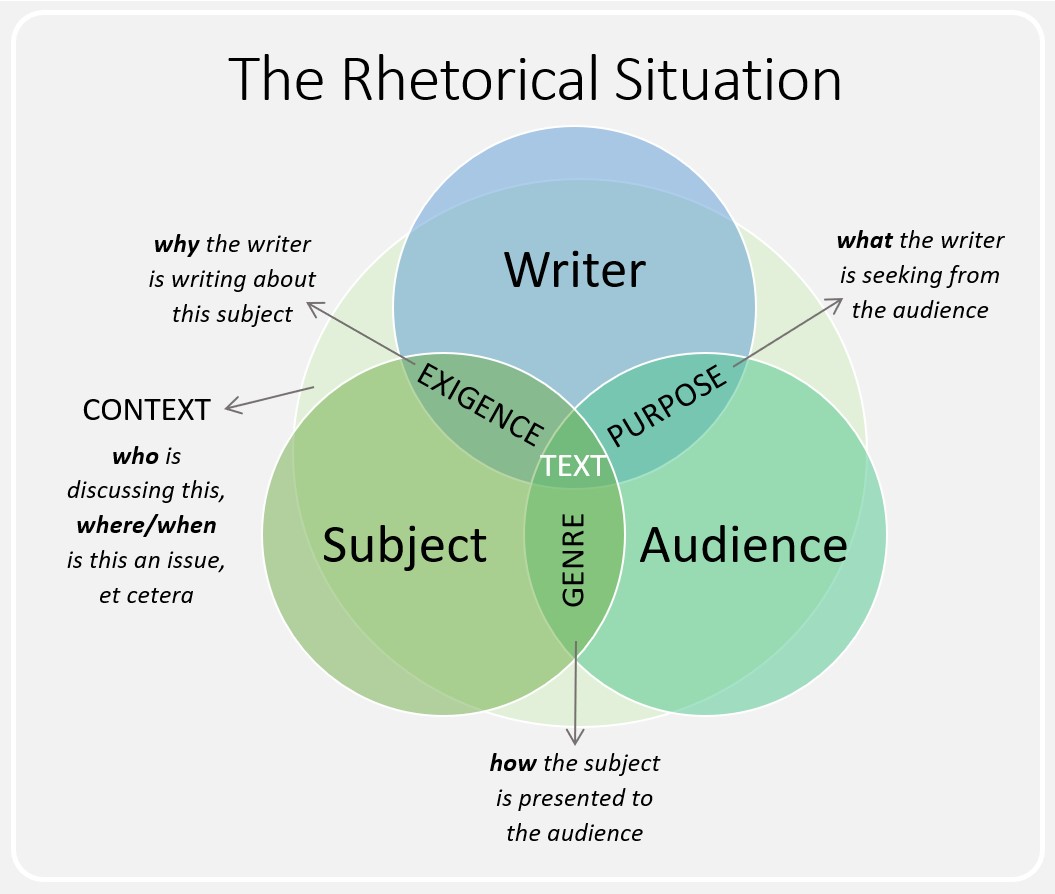

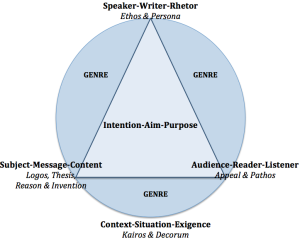

- A Visual Model of the Rhetorical Situation

- Additional Resources on the Rhetorical Situation

by Justin Jory

PROFILE

The term “rhetorical situation” refers to the circumstances that bring texts into existence. The concept emphasizes that writing is a social activity, produced by people in particular situations for particular goals. It helps individuals understand that, because writing is highly situated and responds to specific human needs in a particular time and place, texts should be produced and interpreted with these needs and contexts in mind.

As a writer, thinking carefully about the situations in which you find yourself writing can lead you to produce more meaningful texts that are appropriate for the situation and responsive to others’ needs, values, and expectations. This is true whether writing a workplace e-mail or completing a college writing assignment.

As a reader, considering the rhetorical situation can help you develop a more detailed understanding of others and their texts.

In short, the rhetorical situation can help writers and readers think through and determine why texts exist, what they aim to do, and how they do it in particular situations.

WHAT OTHERS SAY ABOUT THE RHETORICAL SITUATION

Writer

The writer is the individual, group, or organization who authors a text. Every writer brings a frame of reference to the rhetorical situation that affects how and what they say about a subject. Their frame of reference is influenced by their experiences, values, and needs: race and ethnicity, gender and education, geography and institutional affiliations to name a few.

Audience

The audience includes the individuals the writer engages with the text. Most often there is an intended, or target, audience for the text. Audiences encounter and in some way use the text based on their own experiences, values, and needs that may or may not align with the writer’s.

Purpose

The purpose is what the writer and the text aim to do. To think rhetorically about purpose is to think both about what motivated writers to write and what the goals of their texts are. These goals may originate from a personal place, but they are shared when writers engage audiences through writing.

Exigence

The exigence refers to the perceived need for the text, an urgent imperfection a writer identifies and then responds to through writing. To think rhetorically about exigence is to think about what writers and texts respond to through writing.

Subject

The subject refers to the issue at hand, the major topics the writer, text, and audience address.

Context

The context refers to other direct and indirect social, cultural, geographic, political, and institutional factors that likely influence the writer, text, and audience in a particular situation.

Genre

The genre refers to the type of text the writer produces. Some texts are more appropriate than others in a given situation, and a writer’s successful use of genre depends on how well they meet, and sometimes challenge, the genre conventions.

What are the basic elements of rhetorical analysis?

1. The appeal to ethos

Literally translated, ethos means “character.” In this case, it refers to the character of the writer or speaker, or more specifically, his credibility. The writer needs to establish credibility so that the audience will trust him and, thus, be more willing to engage with the argument. If a writer fails to establish a sufficient ethical appeal, then the audience will not take the writer’s argument seriously.

For example, if someone writes an article that is published in an academic journal, in a reputable newspaper or magazine, or on a credible website, those places of publication already imply a certain level of credibility. If the article is about a scientific issue and the writer is a scientist or has certain academic or professional credentials that relate to the article’s subject, that also will lend credibility to the writer. Finally, if that writer shows that he is knowledgeable about the subject by providing clear explanations of points and by presenting information in an honest and straightforward way that also helps to establish a writer’s credibility.

When evaluating a writer’s ethical appeal, ask the following questions:

Does the writer come across as reliable?

- Viewpoint is logically consistent throughout the text

- Does not use hyperbolic (exaggerated) language

- Has an even, objective tone (not malicious but also not sycophantic)

- Does not come across as subversive or manipulative

Does the writer come across as authoritative and knowledgeable?

- Explains concepts and ideas thoroughly

- Addresses any counter-arguments and successfully rebuts them

- Uses a sufficient number of relevant sources

- Shows an understanding of sources used

What kind of credentials or experience does the writer have?

- Look at byline or biographical info

- Identify any personal or professional experience mentioned in the text

- Where has this writer’s text been published?

2. The appeal to pathos

Literally translated, pathos means “suffering.” In this case, it refers to emotion, or more specifically, the writer’s appeal to the audience’s emotions. When a writer establishes an effective pathetic appeal, she makes the audience care about what she is saying. If the audience does not care about the message, then they will not engage with the argument being made.

For example, consider this: A writer is crafting a speech for a politician who is running for office, and in it, the writer raises a point about Social Security benefits. In order to make this point more appealing to the audience so that they will feel more emotionally connected to what the politician says, the writer inserts a story about Mary, an 80-year-old widow who relies on her Social Security benefits to supplement her income. While visiting Mary the other day, sitting at her kitchen table and eating a piece of her delicious homemade apple pie, the writer recounts how the politician held Mary’s delicate hand and promised that her benefits would be safe if he were elected. Ideally, the writer wants the audience to feel sympathy or compassion for Mary because then they will feel more open to considering the politician’s views on Social Security (and maybe even other issues).

When evaluating a writer’s pathetic appeal, ask the following questions:

Does the writer try to engage or connect with the audience by making the subject matter relatable in some way?

- Does the writer have an interesting writing style?

- Does the writer use humor at any point?

- Does the writer use narration, such as storytelling or anecdotes, to add interest or to help humanize a certain issue within the text?

- Does the writer use descriptive or attention-grabbing details?

- Are there hypothetical examples that help the audience to imagine themselves in certain scenarios?

- Does the writer use any other examples in the text that might emotionally appeal to the audience?

- Are there any visual appeals to pathos, such as photographs or illustrations?

Recognizing a Manipulative Appeal to Pathos:

Up to a certain point, an appeal to pathos can be a legitimate part of an argument. For example, a writer or speaker may begin with an anecdote showing the effect of a law on an individual. This anecdote is a way to gain an audience’s attention for an argument in which evidence and reason are used to present a case as to why the law should or should not be repealed or amended. In such a context, engaging the emotions, values, or beliefs of the audience is a legitimate and effective tool that makes the argument stronger.

An appropriate appeal to pathos is different from trying to unfairly play upon the audience’s feelings and emotions through fallacious, misleading, or excessively emotional appeals. Such a manipulative use of pathos may alienate the audience or cause them to “tune out.” An example would be the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) commercials (https://youtu.be/6eXfvRcllV8, transcript here) featuring the song “In the Arms of an Angel” and footage of abused animals. Even Sarah McLachlan, the singer and spokesperson featured in the commercials, admits that she changes the channel because they are too depressing (Brekke).

Even if an appeal to pathos is not manipulative, such an appeal should complement rather than replace reason and evidence-based argument. In addition to making use of pathos, the author must establish her credibility (ethos) and must supply reasons and evidence (logos) in support of her position. An author who essentially replaces logos and ethos with pathos alone does not present a strong argument.

3. The appeal to logos

Literally translated, logos means “word.” In this case, it refers to information, or more specifically, the writer’s appeal to logic and reason. A successful logical appeal provides clearly organized information as well as evidence to support the overall argument. If one fails to establish a logical appeal, then the argument will lack both sense and substance.

For example, refer to the previous example of the politician’s speech writer to understand the importance of having a solid logical appeal. What if the writer had only included the story about 80-year-old Mary without providing any statistics, data, or concrete plans for how the politician proposed to protect Social Security benefits? Without any factual evidence for the proposed plan, the audience would not have been as likely to accept his proposal, and rightly so.

When evaluating a writer’s logical appeal, ask the following questions:

Does the writer organize his information clearly?

- Ideas are connected by transition words and phrases

- Choose the link for examples of common transitions (https://tinyurl.com/oftaj5g).

- Ideas have a clear and purposeful order

Does the writer provide evidence to back his claims?

- Specific examples

- Relevant source material

Does the writer use sources and data to back his claims rather than base the argument purely on emotion or opinion?

- Does the writer use concrete facts and figures, statistics, dates/times, specific names/titles, graphs/charts/tables?

- Are the sources that the writer uses credible?

- Where do the sources come from? (Who wrote/published them?)

- When were the sources published?

- Are the sources well-known, respected, and/or peer-reviewed (if applicable) publications?

Recognizing a Manipulative Appeal to Logos:

Pay particular attention to numbers, statistics, findings, and quotes used to support an argument. Be critical of the source and do your own investigation of the facts. Remember: What initially looks like a fact may not actually be one. Maybe you’ve heard or read that half of all marriages in America will end in divorce. It is so often discussed that we assume it must be true. Careful research will show that the original marriage study was flawed, and divorce rates in America have steadily declined since 1985 (Peck, 1993). If there is no scientific evidence, why do we continue to believe it? Part of the reason might be that it supports the common worry of the dissolution of the American family.

4. The appeal to Kairos

Literally translated, Kairos means the “supreme moment.” In this case, it refers to appropriate timing, meaning when the writer presents certain parts of her argument as well as the overall timing of the subject matter itself. While not technically part of the Rhetorical Triangle, it is still an important principle for constructing an effective argument. If the writer fails to establish a strong Kairotic appeal, then the audience may become polarized, hostile, or may simply just lose interest.

If appropriate timing is not taken into consideration and a writer introduces a sensitive or important point too early or too late in a text, the impact of that point could be lost on the audience. For example, if the writer’s audience is strongly opposed to her view, and she begins the argument with a forceful thesis of why she is right and the opposition is wrong, how do you think that audience might respond?

In this instance, the writer may have just lost the ability to make any further appeals to her audience in two ways: first, by polarizing them, and second, by possibly elevating what was at first merely strong opposition to what would now be hostile opposition. A polarized or hostile audience will not be inclined to listen to the writer’s argument with an open mind or even to listen at all. On the other hand, the writer could have established a stronger appeal to Kairos by building up to that forceful thesis, maybe by providing some neutral points such as background information or by addressing some of the opposition’s views, rather than leading with why she is right and the audience is wrong.

Additionally, if a writer covers a topic or puts forth an argument about a subject that is currently a non-issue or has no relevance for the audience, then the audience will fail to engage because whatever the writer’s message happens to be, it won’t matter to anyone. For example, if a writer were to put forth the argument that women in the United States should have the right to vote, no one would care; that is a non-issue because women in the United States already have that right.

When evaluating a writer’s Kairotic appeal, ask the following questions:

- Where does the writer establish her thesis of the argument in the text? Is it near the beginning, the middle, or the end? Is this placement of the thesis effective? Why or why not?

- Where in the text does the writer provide her strongest points of evidence? Does that location provide the most impact for those points?

- Is the issue that the writer raises relevant at this time, or is it something no one really cares about anymore or needs to know about anymore?

Key Takeaways

Understanding the Rhetorical Situation:

- Identify who the communicator is.

- Identify the issue at hand.

- Identify the communicator’s purpose.

- Identify the medium or method of communication.

- Identify who the audience is.

Identifying the Rhetorical Appeals:

- Ethos = the writer’s credibility

- Pathos = the writer’s emotional appeal to the audience

- Logos = the writer’s logical appeal to the audience

- Kairos = appropriate and relevant timing of subject matter

- In sum, effective communication is based on an understanding of the rhetorical situation and on a balance of the rhetorical appeals.

CC Licensed Content, Shared Previously

English Composition I, Lumen Learning, CC-BY 4.0.

English Composition II, Lumen Learning, CC-BY 4.0.

by Elizabeth Browning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

VISUAL MODELs OF THE RHETORICAL SITUATION

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES ON THE RHETORICAL SITUATION

- “The Rhetorical Situation”—entry published on Wikipedia.com

- “The Rhetorical Situation Poster“—page published bt NCTE (National Council of Teachers of English)