12 Chapter 12 Urban Geography

R. Adam Dastrup

12.1 Defining Cities and Urban Centers

Cities and metropolis

You are probably a city person whether you like it or not. Many people say they do not like the city, with its noise, pollution, crowds, and crime, but living outside the city has its challenges as well. Living outside a city is inconvenient because rural areas lack access to the numerous amenities found in cities. The clustering of activities within a small area is called agglomeration, and it reduces the friction of distance for thousands of daily activities. Cities are convenient places for people to live, work, and play. Convenience has economic consequences, as well. Reduced costs associated with transportation, and the ability to share costs for infrastructure creates what is known as economies of agglomeration, which is the fundamental reason for cities. The convenience and economic benefits of city life have led nearly 8 in 10 Americans to live in urban areas. In California, America’s most urban state, almost 95% of its people live in a city. This chapter explores the evolution of cities, why cities are where they are, and how the geography of cities affects the way urbanites live.

Though it seems simple enough, distinguishing cities from rural areas is not always that easy. Countries around the world have generated a plethora of definitions based on a variety of urban characteristics. Part of the reason stems from the fact that defining what constitutes urban is somewhat arbitrary. Cities are also hard to define because they look and function quite differently in different parts of the world. Complicating matters are the great variety of terms we use to label a group of people living together. Hamlets are tiny, rural communities. Villages are slightly larger. Towns are larger than villages. Cities are larger than towns. Then there are words like metropolis and even megalopolis to denote huge cities. Some states in the United States have legal definitions for these terms, but most do not. The United States Census Bureau creates the only consistent definition of “city,” and it uses the terms “rural” and “urban” to distinguish cities from non-city regions. This definition has been updated several times since the 1800s, most radically in recent years as the power of GIS has allowed the geographers are working for the US Census Bureau to consider multiple factors simultaneously. It can get complex.

For decades, the US Census Bureau recognized an area as “urban” if it had incorporated itself as a city or a town. Incorporation indicates that a group of residents successfully filed a town charter with their local state government, giving them the right to govern themselves within a specific space within the state. Until recently, the US Census Bureau classified almost any incorporated area with at least 2,500 people as “urban.”

There were problems though with that simple definition. Some areas which had quite large populations but were unincorporated, failed to meet the old definition or urban. For example, Honolulu, Hawaii, and Arlington, Virginia are not incorporated, therefore were technically labeled “census-designated places,” rather than cities. Conversely, some incorporated areas may have very few people. This can happen when a city loses population, or when the boundaries of a city extend far beyond the populated core of the city. You may have witnessed this as you are driving on a highway, and you see a sign indicating “City Limits,” but houses, shops, factories and other indicators of urban life are absent yet for many miles. Jacksonville, Florida, is the classic example of this problem. Jacksonville annexed so much territory that its city limits extend far into the adjacent countryside making it the largest city in land area in the United States (874.3 square miles!).

Therefore, the Census Bureau created a complex set of criteria capable of evaluating a variety of conditions that define any location as urban or rural. Among the criteria now used by the Census is a minimum population density of 1,000 people per square mile, regardless of whether the location is incorporated or not. Additionally, a territory that includes non-residential but still urban land uses is included. Therefore, areas with factories, businesses, or a large airport, that contain few residences still counted as part of a city. The Census uses a measure of surface imperviousness to help make such a decision. This means that even a parking lot may be a factor in classifying a place as urban. Finally, the census classifies locations that are reasonably close to an urban region if it has a population density of at least500 persons per square mile. That way, small breaks in the continuity of built-up areas do not result in the creation of multiple urban areas, but instead form a single, contiguous urban region. Therefore, people in the suburbs within five miles of the border of a larger city, are counted by the Census as residents of the urban region, associated with a central city.

City push and pull factors

Cities began to form many thousands of years ago, but there is little agreement regarding why cities form. The chances are that many different factors are responsible for the rise of cities, with some cities owing their existence to multiple factors and cities arose as a result of more specific conditions.

Two underlying causal forces contribute to the rise of cities. Site location factors are those elements that favor the growth of a city that is found at that location. Site factors include things like the availability of water, food, good soils, a quality harbor, and characteristics that make a location easy to defend from attack. Situation factors are external elements that favor the growth of a city, such as distance to other cities, or a central location. For example, the exceptional distance invading armies have had to travel to reach Moscow, Russia has helped the city survive many wars. Most large cities have good site and situation factors.

Indeed, the earliest incarnation of cities offered residents a measure of protection against violence from outside groups for thousands of years. Living in a rural area, farming or ranching, made any family living in such isolation vulnerable to attack. Small villages could offer limited protection, but larger cities, especially those with moats, high walls, professional soldiers, and advanced weaponry, were safer.

The safest places were cities with quality defensible site locations. Many of Europe’s oldest cities were founded on defensible sites. The European feudal system was built upon an arrangement whereby the local lord/duke/king supplied protection to local rural peasants in exchange for food and taxes. For example, Paris and Montreal were founded on defensible island sites. Athens was built upon a defensible hillside, called an acropolis. The Athenian Acropolis is so famous that it is called merely The Acropolis. On the other hand, Moscow, Russia, takes advantage of its remote situation. Both Napoleon and Hitler found out the hard way the challenges associated with attacking Moscow.

In the United States, the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans have primarily functioned as America’s defensive barriers, and therefore few cities are located on defensive sites. Washington, D.C. has no natural defense-related site or situation advantages. On the only occasion the US was invaded, the city was overrun by the British in the War of 1812. The White House and the Capitol were burned to the ground. The poor defensibility of the American capital led to numerous calls for its relocation to a more defensible site during the 1800s. This is partly the reason, so many state-capitol buildings in the Midwest closely resemble the US Capitol building in Washington D.C.; many states were trying to lure the seat of the Federal government to their state capital.

People who possess a specific skill set to become a site factor that can significantly affect the location and growth of a city. One specialized skill set was confined to the priestly class, and proximity to religious leaders is another probable reason for the formation of cities. Priests and shamans would have likely gathered the faithful near to them, so that, as the armies of the lordly class, they could offer protection and guidance in return for food, shelter, and compensation (like tithes). The priestly class was also the primary vessels of knowledge – and the tools of knowledge like writing and science (astronomy, planting calendars, medicine, e.g.), so a cadre of assistants in those affairs would have been necessary. Mecca and Jerusalem are probably the best examples of holy cities, but others dot the landscape of the world. Rome existed before the Catholic faith, but it assuredly grew and prospered as a result of becoming the headquarters of Christianity for hundreds of years.

Cities may have evolved as small trading posts where local farmers and wandering nomads exchanged agricultural and craft goods. The surplus wealth generated through trade required protection and fortifications, so cities with walls may have been built to protect marketplaces and vendors. Some trace the birth of London to an ancestral trading spot called Kingston upon the Thames, a market town founded by the Saxons southwest of London’s present core. The place names of many ancient towns in England reveal their original function – Market Drayton, Market Harborough, Market Deeping, Market Weighton, Norton Chipping, Chipping Ongar and Chipping Sodbury. “Chipping” is a derivation of a Saxon word meaning “to buy.”

Throughout history, cities, big and small, have served market functions for those who live in adjacent hinterlands. Some market cities grow much more substantial than others because they are more centrally located. Central location relative to other competing marketplaces is another example of an ideal situation factor. Large cities have excellent site and situation characteristics. Every major US city, including New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Houston is located ideally for commerce and industry.

Some cities grow large because of specific site location advantages that favor trade or industry. All cities compete against one another to attract industry, but only those with quality site factors, like excellent port facilities and varied transportation options grow large. Cities ideally located between significant markets for exports and imports have excellent situation factor advantages versus other competing cities and will grow most.

Most large cities in the United States emerged where two or more modes of transportation intersect, forming what geographers call a break of bulk point. Breaking bulk happens whenever cargo is unloaded from a ship, truck, barge, or train. Until the 1970s, unloading (and reloading) freight required a vast number of laborers, and therefore any city that had a busy dock or port or station attracted workers. Los Angeles, Chicago, New Orleans, and Houston all grew very large because each was well served by multiple transportation modes.

12.2 Understanding Distribution and City Size

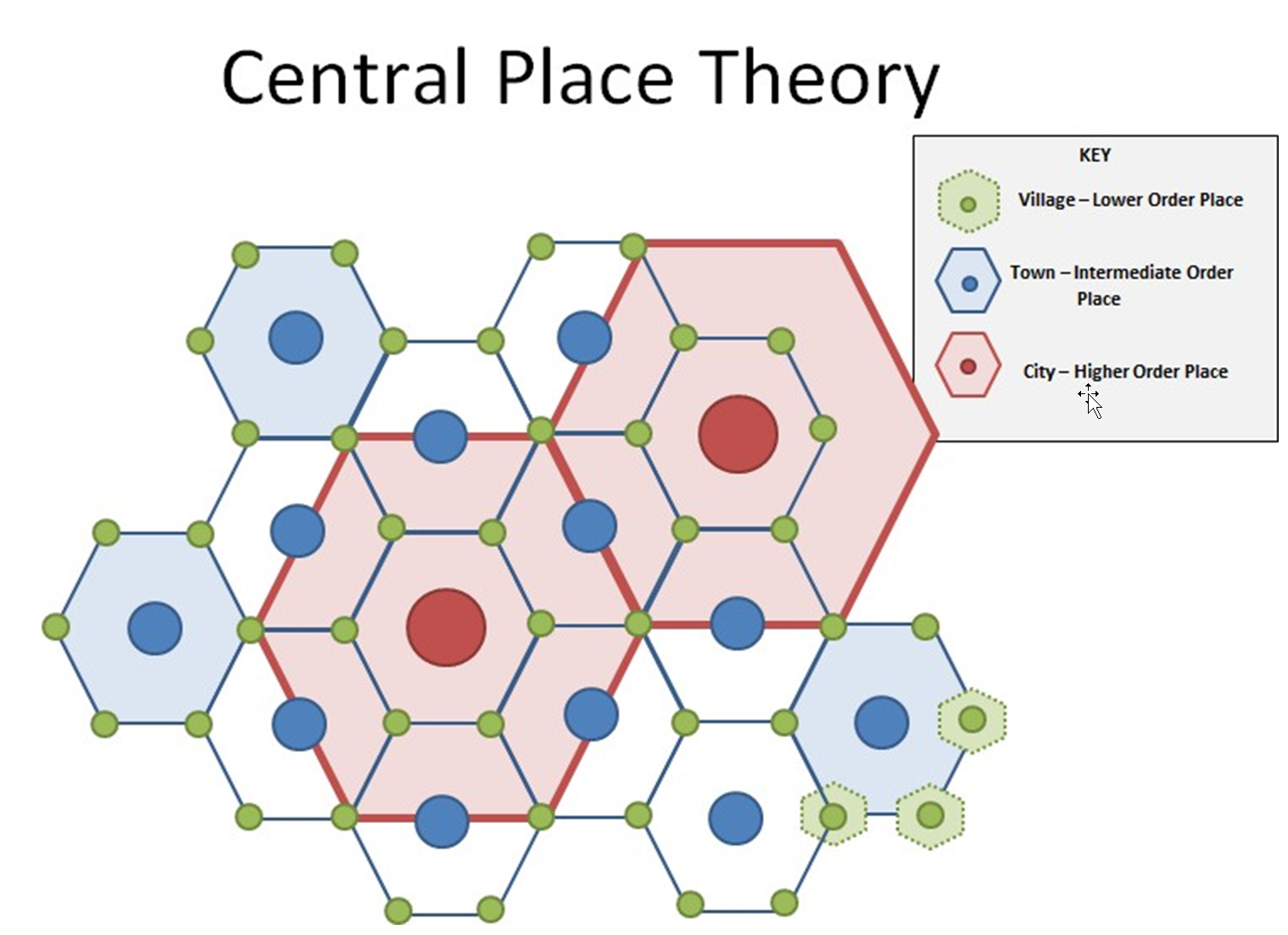

Under very unusual circumstances, one might find that among a group of cities, no single city has unique site location advantages over others. This might happen out on a vast plain, like in Kansas, where there are no navigable rivers, waterfalls or ports. In instances like this, situation advantages come to the fore, and a regular, geometric pattern of cities may emerge. This process was more pronounced when transportation was primitive, and the friction of distance was considerable, but it can still be witnessed by picking up a map of almost any flat region of the earth. Geographer Walter Christaller noticed the pattern and developed the Central Place Theory to explain the pattern and the logic driving it forward.

According to Christaller, if a group of people (like farmers) diffuse evenly across a plain (as they were when Kansas opened for homesteaders), a predictable hierarchy of villages, towns, and cities will emerge. The driving force behind this pattern is the basic need everyone has to go shopping for goods and services. Naturally, people prefer to travel less to acquire what they need. The maximum distance people will travel for a good or service is called the range of that good or service. Goods like a hammer have a short range because people will not travel far to buy a hammer. A tractor, because it is an expensive item, has a much greater range. The cost of getting to a tractor dealership is small about the cost of the tractor itself, so farmers will travel long distances to buy the one they want. Hospital services have even greater ranges. People might travel to the moon if a cure for a deadly disease was available there.

Each merchant and service provider also requires a minimum number of regular customers in order to stay in business. Christaller called this number the threshold population. A major-league sports franchise has a threshold population of probably around a million people, most of whom must live in that team’s range. There are only 30 Major League Baseball teams in the United States, and the team with the smallest market (Milwaukee Brewers) has a threshold population of 2 million people. An ordinary Wal-Mart store probably has a threshold of about 20,000 people, so they are far more numerous. Starbuck’s Coffee shops probably have a threshold of about 5,000 people or less, because there are so many locations.

When customers and merchants living and working on featureless plain interact over time, some villages will attract more merchants (and customers) and grow into towns or even cities. Some villages will not be able to attract or retain merchants, and they will not grow. Competition between towns on this plain prevents nearby locations from growing simultaneously. As a result, centrally located villages tend to grow into towns at the expense of their neighbors. A network of centrally located towns, will emerge, and among these towns, only a few will grow into cities. One very centrally located city may evolve into a much larger city.

The largest cities will have business and functions that require significant thresholds (like major league sports teams or highly specialized boutiques). People from villages and small towns can access only the most essential goods and services (like gas stations or convenience stores) and are forced to travel to larger cities to buy higher order goods and services. Those goods and services not available to the nearest large city (regional service center) require customers to travel further. Some goods and services are only available at the top of the urban hierarchy; the mega-cities. In the United States, a handful of cities (New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Dallas) may offer exceptionally high order goods, unavailable in other large cities like Cleveland, Seattle or Atlanta.

Understanding Internal City Structure and Urban Development

Most urban centers begin in the downtown region called the central business district (CBD). The CBD tends to be the node or of transportation networks along with commercial property, banking, journalism, and judicial departments like City Hall, courts, and libraries. Because of high competition and limited space, property values for commercial and private ownership tend to be at a premium. CBDs also tend to use land above and below ground in the form of subways, underground malls, and high- rises. Sports facilities and convention centers also tend to be dominating forces in CBDs.

Urban planning is a sub-field of geography and until recently was part of geography departments in academia. An urban planner is someone trained in multiple theories of urban development along with developing ways to minimize traffic, decrease environmental pollution, and build sustainable cities. Urban planners, sociologists, along with geographers, have come up with three models to demonstrate and explain how cities grow.

The first model is called the concentric zone model, which states that cities can develop in five concentric rings. The inner zone of the cities tends to be the CBD, followed by a second ring that tends to the zone of transition between the first and third rings. In this transition zone, the land tends to be used by industry or low-quality housing. The third ring is called the zone of independent workers and tends to be occupied by working-class households. The fourth ring is called the zone of better residences and is dominated by middle-class families. Finally, ring five is called the commuter’s zone, where most people living there have to commute to work every day.

The second model for city development and growth is called the sector model. This model states that cities tend to grow in sectors rather than concentric rings. The idea behind this model is that “like groups” tend to grow in clusters and expand as a cluster. The center of this model is still the CBD. The next sector is called the transportation and industry sector. The third sector is called the low-class residential sector, where lower-income households tend to group. The fourth sector is called the middle-class sector, and the fifth is the high-class sector.

The third and final urban design is called the multiple nuclei model. (See figure 7.16) In this model, the city is more complex and has more than one CBD. A node could exist for the downtown region, another where a university is situated, and maybe another where an international airport may be. Some clustering does exist in this model because some sectors tend to stay away from other sectors. For example, the industry does not tend to develop next to high-income housing.

The multiple nuclei model also features zones common to the other models. Industrial districts in these new cities, unfettered by the need to access rail or water corridors, rely instead on truck freight to receive supplies and to ship products, allowing them to occur anywhere zoning laws permitted. In western cities, zoning laws are often far less rigid than in the East, so the pattern of industrialization in these cities is sometimes random. Residential neighborhoods of varying status also emerged in a nearly random fashion as well, creating “pockets” of housing for both the rich and poor, alongside large zones of lower-middle-class housing. The reasons for neighborhoods to develop where they do are similar as they are in the sector model. Amenities attract wealthier people, transport advantages attract industry and commerce, and disamenity zones are all that poor folks can afford. There is a sort of randomness to multiple nuclei cities, making the landscape less legible for those not familiar with the city, unlike concentric ring cities that are easy to read by outsiders who have been to other similar cities.

Another model is referred to as “Keno Capitalism.” In this model, based in Los Angeles, different districts are laid out in a mostly random grid, similar to a board used in the gambling game keno. The premise of this model is that the internet and modern transportation systems have made location and distance mostly irrelevant to the location of different sorts of activities within a city.

Geographers Ernest Griffin and Larry Ford recognized that the popular urban models did not fit well in many cities in the developing world. In response, they created one of the more compelling descriptions of cities formerly colonized by Spain – the Latin American Model. The Spanish designed Latin American cities according to rules contained in the Spanish Empire’s Law of the Indies. According to these rules, each significant city was to have at its center a large plaza or town typical for ceremonial purposes. A grand boulevard along which housing for the city’s elite was built stretched away from the central plaza and served as both a parade route and opulent promenade. For several blocks outward from this elite spine was built the housing for the wealthy and powerful.

The rest of the city was initially left for the poor because there was almost no middle class. The poorly built houses close the central plaza where jobs and conveniences existed. Over time, the houses built by the poor, perhaps little more than shacks, were improved and enlarged. Ford and Griffin called this process in situ accretion. As the city’s population grew, young families and in-migrants built still more shacks, adding rings of housing that is always being upgraded. At the edges of the city are always the newest residents, often squatting on land they do not own.

Sociologists, geographers, and urban planners know that no city exactly follows one of the urban models of growth. However, the models help us understand the broader reason why people live where they do. Higher income households tend to live away from lower income households. Renters and house owners also tend to segregate from each other. Renters tend to live closer to the CBD, whereas homeowners tend to live in the outer regions of the city. It should be noted that the three models were developed shortly after World War II and based on U.S. cities; many critics now state that they do not truly represent modern cities.

Megacities

A megacity is pegged as any city with more than 10 million residents. Another term often used to describe this is conurbation, a somewhat more comprehensive label that incorporates agglomeration areas such as the Rhine-Ruhr region in Germany’s west which has 11.9 million inhabitants.

Of the 30 biggest megacities worldwide, 20 of them are in Asia and South America alone, including Baghdad, Bangkok, Buenos Aires, Delhi, Dhaka, Istanbul, Jakarta, Karachi, Kolkata, Manila, Mexico City, Mumbai, Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto, Rip de Janeiro, Sao Paulo, Seoul, Shanghai, Teheran, and Tokyo-Yokohama. European megacities include London and Paris, and the UN estimates that the number of megacities worldwide will only increase.

The explosive growth of these and other cities is a rather new phenomenon, a result of industrialization. The megacities of the world differ not only according to whether they lie in the southern or northern hemisphere, but also by country, climatic, political, economic, and social conditions. Megacities can be productive, poor, organized, or chaotic. Paris and London are megacities, but it is difficult to compare them demographically or economically with Jakarta or Lagos. Vibrant megacities tend to stretch out further than their poorer counterparts: Los Angeles’ settlement area is four times as big as Mumbai’s despite its population being smaller. Wealthy city inhabitants have a much higher rate of land consumption for apartments, transport, business, and industry. The situation is similar in terms of water and energy consumption, which is much higher in affluent cities. Cairo and Dhaka are without doubt ‘monster cities’ in terms of their population size, spatial, and urban planning. However, they are also “resourceful cities,” home to millions of people with few resources.

The high population levels in megacities and mega-urban spaces are leading to a host of problems such as guaranteeing all residents a supply of essential foods, drinking water and electricity. Related to this are concerns about sanitation and disposal of sewage and waste. There is not enough living space for incoming residents, leading to an increase in informal settlements and slums. Many urban residents get around via bus, truck or motorized bicycles, leading to chaos on the streets and CO2 emissions leaking into the air.

The faster a city develops, the more critical these issues become. Due to their rapid growth, megacities in developing countries and the southern hemisphere have to battle in order to provide for their inhabitants. Between 1950 and 2000, cities in the north have grown an average of 2.4 times. In the south, they have grown more than 7-fold over the same period. Lack of financial resources and sparse coordination between stakeholders at different levels intensify the problems. Megacities usually do not represent one political-administrative unit, instead of dividing the city into parts such as with Mexico City, which is made up of one primary core district (Distrito Federal) and more than 20 outlying municipalities, where differing planning, construction, tax, and environmental laws are carried out than in the core district.

Two key causes behind city growth are high rates of immigration as well as growing birth numbers. People move to the city with the hope of a more prosperous life and leave the country in search of brighter prospects. Without careful planning and infrastructure in place, this road can often lead to another poverty trap. As cities grow, so too do the unplanned and underserved areas, the so-called slums. In some regions of the world, more than 50 percent of urban populations live in slums. In parts of Africa south of the Sahara, that number jumps to around 70 percent. In 2007, a reported one billion people lived in slums, and by 2020, that figure could grow to 1.4 billion, according to the UN.

The United Nations defines slums as overcrowded, inadequate, informal forms of housing that lack reasonable access to clean drinking water and sanitary facilities and deprive residents of power of the land. Above all, slums are an architectural and spatial expression of lack of housing and growing urban poverty. The well-known symbols of this are makeshift huts, such as the favelas in Brazil, but also desolate and overcrowded apartment buildings in major Chinese cities where the growing army of migrant workers and workers find makeshift accommodation.

The reasons so many of these cities are poor include underemployment and insufficient pay as well as low productivity within the informal sector. Around half the people in megacities that lie in the southern hemisphere are employed in the informal sector, many of whom are coerced into accepting any employment. They sell various products – cigarettes, drinks, food, bits, and pieces – simple services like shoe cleaning and letter writing as well as smuggling goods or ending up in prostitution. Exploitation is, at times, rife in slum settings due to insecure residences, lack of legal protection, poor sanitation, and unstable acquisition conditions.

Parallel to the growth of slums, gated communities – or exclusive neighborhoods – are also on the rise. These are fenced and well-monitored communities in which affluent members live, further driving the trend towards separation among urban populations.

However, it is not just living spaces splitting the cities – globally; there is a significant push towards big new building projects like über-modern banks and business districts which stand in stark contrast to informal areas for the poor. These central business districts (CBD) are often siloed off from the central part of the city and migrate, along with the gated communities, towards the outskirts of town as is the case in Pudong, Shanghai, and Beijing.

For the most part, urban planning is based on the needs of the consumer and culture-oriented upper classes and economic growth sectors, with the result being that the gap between rich and poor continues to grow. Such fragmented cities are a fragile entity in which conflicts are inevitable.

Because most people on the planet are city-dwellers, questions are starting to be asked about how to develop and design urbanization and urban migration in a sustainable way. Urban residents the world over require good air to breathe, clean drinking water, access to proper healthcare, sanitary facilities, and reliable energy supply.

The current situation in cities in developing countries can be precarious: the air is thick enough to touch; sewage treatment plants, if any, are overloaded and industrial factories secrete virtually unregulated highly toxic waste and wastewater. Also, climate change will likely hit more impoverished cities harder. However, cities in the developed countries have to deal with environmental challenges in the areas of transport, energy and waste and wastewater.

On an international level, there are countless efforts currently being undertaken to support sustainable urban development. Several large UN projects, such as the UN-HABITAT Program and the Sustainable Urban Development Network are endeavoring to improve and strengthen governmental and planning abilities. One of the goals of the UMP is also to implement the Millennium Development Goals at the city level.

Many urban problems can be explained not only at the city level, but must be regarded as results of political disorder and economic instability on a global and national level – and that this is where the solutions lie!

12.3 Challenges to Urban Growth

One of the major problems that cities face is deteriorating areas, high crime, homelessness, and poverty. As noted in the urban models, many lower-income people live near the city, but lack the job skills to compete for employment within the city. This often results in a variety of social and economic problems. Census data shows that 80 percent of children living in inner cities only have one parent, and because child care services are limited in the city, single parents struggle to meet the demands of childcare and employment. Problems associated with lower income areas are often violent crime (assault, murder, rape), prostitution, drug distribution, and abuse, homelessness, and food deserts.

Slums and Shanty Towns

Some of these inner-city areas are slums, which is a densely populated urban informal settlement consisting of poor, inadequate living standards. Most slums lack proper sanitation services, access to clean drinking water, law enforcement, or other necessities of living in an urban area.

A shanty town, also known as a squatter, is a slum settlement that usually consists of building material made from plywood sheets of plastic, cardboard boxes, and other cheap material. They are usually found on the periphery of cities or near rivers, lagoons, or city trash dumps.

When residents in a neighborhood lack the money, political organizational skills, or the motivation to protect themselves from disamenities, defined as drawbacks or disadvantages, especially about location, significant neighborhood degradation is possible. Poor people of all ethnicities can rarely afford to live in neighborhoods that have the outstanding schools, parks, air quality, etc., and so they are often able to afford to live only in the most dangerous, toxic, degraded neighborhoods. Racism is undoubtedly a common variable in the poverty equation, but it is rarely the only one.

Gentrification

As a way for city officials to deal with inner-city problems, there has been a push recently to renovate cities, a process called gentrification. Middle-class families are drawn to city life because housing is cheaper, yet can be fixed up and improved, whereas suburb housing prices continue to rise. Some cities also offer tax breaks and cheap loans to families who move into the city to help pay for a renovation. Also, city houses tend to have more cultural style and design compared to quickly made suburb homes. Transportation tends to be cheaper and more convenient, so that commuters do not spend hours a day traveling to work. Couples without children are drawn to city living because of the social aspects of theaters, clubs, restaurants, bars, and recreational facilities.

The logic behind gentrification is that it not only reduces crime and homelessness; it also brings tax revenue to cities to improve the city’s infrastructure. However, there has also been a backlash against gentrification because some view it as a tax break for the middle and upper class rather than spending much-needed money on social programs for low-income families. It could also be argued that improving lower class households would also increase tax revenue because funding could go toward job skill training, child care services, and reducing drug use and crime.

Homelessness

Homelessness is another primary concern for citizens of large cities. More than one half- million people are believed to live on the streets or in shelters. In 2013, about one- third of the entire homeless population were living as a member of a family unit. One-fourth of homeless people were children. In Los Angeles County at the same time, there were somewhere around 40,000 homeless people living either in shelters and on the street. Another 20,000 persons were counted as near homeless or precariously housed, typically living with friends or acquaintances in short-term arrangements.

There are multiple reasons why people become homeless. The Los Angeles Homeless Authority estimates that about one-third of the homeless have substance abuse problems, and another third are mentally ill. About a quarter have a physical disability. A disturbing number are veterans of the armed forces or victims of domestic abuse. Economic conditions locally and nationally also have a significant impact on the overall number of homeless people in a particular year, not only because during recessions people lose their jobs and homes, but because the stresses of poverty can worsen mental illness.

The government plays a significant role in the pattern and intensity of homelessness. Ronald Reagan is the politician most associated with the homeless crisis both nationally and in California. When Reagan became governor of California, the late 1960s, deinstitutionalization of people with a mental health condition was already a state policy. Under his administration, state-run facilities for the care of mentally ill persons were closed and replaced by for-profit board and care homes. The idea was that people should not be locked up by the state solely for being mentally ill and that government-run facilities could not match the quality and cost-efficiency of privately run boarding homes. Many private facilities, though were severely run, profit-driven, located in poor neighborhoods and had little professional staff. Patients could, and did, leave these facilities in large numbers, frequently becoming homeless or incarcerated. Other states followed California’s example. By the late 1970s, the federal government passed some legislation to address the growing crisis, but sweeping changes in governmental policy at the federal level during the Regan presidency shelved efforts started by the Carter administration. Drastic cuts to social programs during the 1980s ensured an explosion of mental illness related homelessness. Most funding has never been restored, though the Obama administration has aggressively pursued policies aimed at housing homeless veterans.

Though homeless people come from many types of neighborhoods, facilities for serving homeless populations are not well distributed throughout the urban regions. Many cities have a region known as Skid Row, a neighborhood unofficially reserved for the destitute. The term originated as a reference to Seattle’s lumber yard areas where workers used skids (wooden planks) to help them move logs to mills. Today, many of the shelters and services for the homeless are found in and around skid row.

12.4 Urban and Suburban Sprawl

Not all of a city’s residents live within the urban cores. Over half of all people live in the suburbs rather than in the city or rural areas. There was a suburban sprawl model developed to explain U.S. development called the peripheral model. This model states that urban areas consist of a CBD followed by large suburban are of business and residential developments. The outer regions of the suburbs become transition zones of rural areas.

The attraction to suburbs is low crime rates, lack of social and economic problems, detached single-family housing, access to parks, and usually better schooling. These are nationwide generalizations and not necessarily true everywhere. Suburbs also tend to create economic and social segregation, where tax revenues and social resources provide better funding opportunities than in inner cities.

Of course, there is also a cost to suburban sprawling. Developers are always looking for cheaper land to build, which usually means developing rural areas and farmland rather than expanding next to existing suburbs. Air pollution and traffic congestion also become a problem as working households are required to travel farther to and from work. Suburbs tend to be less commuter friendly to those who walk or bike because the model of development is based around vehicle transportation.

Water is another challenge to urban growth. It is an elemental part of the fabric of urban lives, providing sustenance and sanitation, commerce, and connectivity. Our fundamental needs for water have always determined the location, size, and form of our cities, just as water shapes the character and outlook of their citizens. Urban health is inextricably linked with water. From the first cities, planners have appreciated the potential linkages of water with health and the need for consistent water supplies. Indeed, the modern field of public health owes a substantial debt to the sanitary engineers who strove to provide potable water and safe disposal of human wastes in burgeoning cities of the Industrial Revolution.

Scientists and decision-makers have recently begun to appreciate that, as in the case of other urban systems, the linkages between water management, health and sustainability are involved in ways that undermine the effectiveness of traditional approaches. Unprecedented urban populations and densities, intra-urban inequities, and inter-urban mobility pose serious new problems, and climate change adds a novel and uncharted dimension. This has, in some cases, led to worsening urban health, or increased risks—for instance, some water-associated diseases like dengue are on the rise globally while others, like cholera, nominally controlled in the developed countries, continue to pose serious threats elsewhere; many regions face increased food and water scarcity, and many urban slums present conditions that challenge effective water management.

12.5 Cities as a Place

In one way, cities are vast, complex machines that produce goods and services, but that way of conceiving the city overlooks genuine emotional qualities that define almost any location. Most people would argue that cities have personalities; qualities that define them as a place. People who live in particular cities often develop a sort of tribal attitude toward their city. This attitude is reflected most visibly in the genuine, emotional attachment citizens have to their sports teams. It is not uncommon for citizens of a city to take great offense at derogatory remarks directed toward “their city,” especially if those remarks come from an outsider.

How we know what we know about cities is primarily bound up in the symbolism of cities provided us through countless media. Often people have enormous storehouses of knowledge about specific places (New York, Paris, Hollywood), even though they have never even visited. We also have powerful ideas about generic places, “small towns,” “the suburbs,” “the ghetto,” even though we may not have visited these places either. This knowledge is imperfect and may very well be dangerously inaccurate to both those people who live in these places and us. It is essential that we recognize how our knowledge of places has been constructed, and we must seek to understand what purposes these constructions serve.

Geographer Donald Meinig proposed that Americans have particularly strong ideas and emotions about three unique, but generic landscapes: The New England Village, Small Town America and the California Suburb (Meinig’s Three Landscapes). Scholars who specialize in the theory of knowledge would suggest these are landscapes are “always already” known; because the symbolism associated with them is deeply ingrained in our collective thoughts, despite that fact that we are hard-pressed to identify how we came to understand the symbolism associated with these places.

Meinig’s first symbolic landscape is the sleepy New England Village, with its steepled white church and cluster of tidy homes surrounded by hardwood forests is powerfully evocative of a lifestyle centered around family, hard work, prosperity, Christianity, and community. He called its rival from the American Midwest Main Street USA. This landscape is found in countless small towns, and symbolizes order, thrift, industry, capitalism, and practicality. It is less cohesive and less religious than the New England Village, and more focused on business and government. Finally, Meinig points to the California Suburb as the last of the significant urban landscapes deeply embedded in the national consciousness. Suburban California symbolizes the good-life: backyard cookouts with the family and neighbors, a prosperous, healthy lifestyle, centered on family leisure.

So powerful are these images that they often appear as settings for novels, movies, television shows as well as political or product advertising campaigns. If you were a manufacturer of high-quality home furnishings, you might want to use the landscape of New England to help sell a well-built dining room table. Insurance companies, like to evoke images of Main Street USA when they want to sign you up for a policy; “like a good neighbor,” they might tell you, hoping you will trust the company, even though its headquarters is not in a small farming town. E.T., the famous movie about a boy who befriends a lost space alien is set in a “typical California suburb.” Like the other symbolic landscapes, movie audiences do not need to have the setting explained to them; they always already know what that place means. Indeed, there are other symbolic landscapes.

Cultural Reflections in Urban Landscapes

The built environment is a product of socio-economic, cultural, and political forces. Every urban system has its own ‘genetic code,’ expressed in architectural and spatial forms that reflect a community’s values and identity. Each community chooses specific physical characteristics, producing the unique character of its city. This ‘communal eye’ exemplifies the city’s architectural legacy and gives a sense of place.

For example, in old Sana’a, the capital of Yemen, unique buildings decorated with geometric patterns create a distinctive visual character unique to the city (Figure 7.23) Another example is Egypt’s Nubian village (Figure 7.24) where the building materials and colors are unique and reflect the vernacular architecture of the region.

However, current architectural practices, in almost every city in the world, do not respect the past identities and traditions of our cities. Most projects bear little or no relationship to the surrounding urban context the city’s genetic code. Architects only follow international architectural movements such as “Modern architecture,” “Postmodernism,” “High-Technology,” and “Deconstructionism.” The result is a fragmented and discontinuous dialogue among buildings, destroying a city’s communal memory.

Street art and graffiti have been filling this gap, explaining the conflict between the traditional culture and contemporary sociopolitical issues of cities. Street artists are repurposing city walls to highlight heritage, history, and identity and, in some cases, to humanize this struggle. Each city has a unique wall art that has become part of its overall genetic code. Some of the art in Santiago (Figure 7.25), for example, highlights Chilean identity. Another example is how wall art was used during the Egyptian revolution to memorialize the events. In March 2012, young graffiti artists launched the “No Walls” movement when the Egyptian authorities constructed several concrete walls to block important street junctions to control peaceful demonstrations.

Many scholars of urban morphology suggest that the street network of any city is made up of a dual network −the foreground network, consisting of the main streets in the urban system, and background network, made up of alleyways or smaller streets. The foreground network, or the leading street network, usually have a universal form, a ‘deformed wheel’ structure composed of small semi-grid street pattern in the center (hub) linked with at least one ring road (rim) through diagonal streets (spokes). However, the form of the background network differs from a city to another; therefore, it is this network that gives a city its spatial identity.

Many cities such as London, Tokyo, and Cairo have a similar universal street pattern of a ‘deformed wheel’ in foreground network despite having different background networks, possibly as a result of cultural differences or contributing to the creation of those cultural differences. In short, the background network reflects the unique structure of each city, and could be considered its genetic code.

Economic Development and City Infrastructure

The evidence of the definite link between urban areas and economic development is overwhelming. With just 54 percent of the world’s population, cities account for more than 80 percent of global GDP. Figure 7.24 and Figure 7.25 respectively show the contribution of cities in developed and developing countries to national income. In virtually all cases, the contribution of urban areas to national income is more significant than their share of the national population. For instance, Paris accounts for 16 percent of the population of France, but generates 27 percent of GDP. Similarly, Kinshasa and metro Manila account for 13 percent and 12 percent of the population of their respective countries, but generate 85 percent and 47 percent of the income of the democratic republic of Congo and Philippines respectively. The ratio of the share of urban areas’ income to share of the population is more considerable for cities in developing countries vis-à-vis those of developed countries. This is an indication that the transformative force of urbanization is likely to be higher in developing countries, with possible implications for harnessing the positive nature of urbanization.

The higher productivity of urban areas stems from agglomeration economies, which are the benefits firms and businesses derive from locating near to their customers and suppliers in order to reduce transport and communication costs they also include proximity to a vast labor pool, competitors within the same industry and firms in other industries.

These economic gains from agglomeration can be summarized as three essential functions: matching, sharing, and learning. First, cities enable businesses to match their distinctive requirements for labor, premises, and suppliers better than smaller towns because a more extensive choice is available. Better matching means greater flexibility, higher productivity, and stronger growth. Second, cities give firms access to a bigger and improved range of shared services, infrastructure, and external connectivity to national and global customers because of the scale economies for providers. Third, firms benefit from the superior flows of information and ideas in cities, promoting more learning and innovation. Proximity facilitates the communication of complex ideas between firms, research centers, and investors. Proximity also enables formal and informal networks of experts to emerge, which promotes comparison, competition, and collaboration. It is not surprising, therefore, that large cities are the most likely places to spur the creation of young high growth firms, sometimes described as “gazelles.” It is cheaper and easier to provide infrastructure and public services in cities. The cost of delivering services such as water, housing, and education is 30-50 percent cheaper in concentrated population centers than in sparsely populated areas.

The benefits of agglomeration can be offset by rising congestion, pollution, pressure on natural resources, higher labor and property costs; greater policing costs occasioned higher levels of crime and insecurity often in the form of negative externalities or agglomeration diseconomies. These inefficiencies grow with city size, especially if urbanization is not adequately managed, and if cities are deprived of essential public infrastructure. The immediate effect of dysfunctional systems, gridlock, and physical deterioration may be to deter private investment, reduce urban productivity, and hold back growth. Cities can become victims of their success, and the transformative force of urbanization can diminish.

The dramatic changes in the spatial form of cities brought about by rapid urbanization over the last two decades, present significant challenges and opportunities. Whereas new spatial configurations play a crucial role in creating prosperity, there is an urgent demand for more integrated planning, robust financial planning, service delivery, and strategic policy decisions. These interventions are necessary if cities are to be sustainable, inclusive, and ensure a high quality of life for all. Urban areas worldwide continue to expand, giving rise to an increase in both vertical and horizontal dimensions.

With cities growing beyond their administrative and physical boundaries, conventional governing structures and institutions become outdated. This trend has led to expansion not just in terms of population settlement and spatial sprawl, but has altered the social and economic spheres of influence of urban residents. In other words, the functional areas of cities and the people that live and work within them are transcending physical boundaries.

Cities have extensive labor, real estate, industrial, agricultural, financial and service markets that spread over the jurisdictional territories of several municipalities. In some cases, cities have spread across international boundaries plagued with fragmentation, congestion, degradation of environmental resources, and weak regulatory frameworks; city leaders struggle to address demands from citizens who live, work, and move across urban regions irrespective of municipal jurisdictional boundaries. The development of complex interconnected urban areas introduces the possibility of reinventing new mechanisms of governance.

A city’s physical form, its built environment characteristics, the extent and pattern of open spaces together with the relationship of its density to destinations and transportation corridors, all interact with natural and other urban characteristics to constrain transport options, energy use, drainage, and future patterns of growth. It takes careful, proper coordination, location and design (including mixed uses) to reap the benefits more compact urban patterns can bring to the environment (such as reduced noxious emissions) and quality of life.

Urban space can be a strategic entry point for driving sustainable development. However, this requires innovative and responsive urban planning and design that utilizes density, minimizes transport needs and service delivery costs, optimizes land- use, enhances mobility and space for civic and economic activities, and provides areas for recreation, cultural and social interaction to enhance the quality of life. By adopting relevant laws and regulations, city planners are revisiting the compact and mixed land-use city, reasserting notions of urban planning that address the new challenges and realities of scale, with urban region-wide mobility and infrastructure demands.

The need to move from sectoral interventions to strategic urban planning and more comprehensive urban policy platforms is crucial in transforming city form. For example, transport planning was often isolated from land- use planning, and this sectoral divide has caused wasteful investment with long-term negative consequences for a range of issues including residential development, commuting, and energy consumption. Transit and land- use integration is one of the most promising means of reversing the trend of automobile-dependent sprawl and placing cities on a sustainable pathway.

The more compact a city, the more productive and innovative it is and the lower it is per capita resource use and emissions. City planners have recognized the need to advance higher density, mixed-use, inclusive, walkable, bikeable, and public transport-oriented cities. Accordingly, sustainable and energy-efficient cities, low carbon, with renewable energy at scale are re-informing decision making on the built environment.

Despite shifts in planning thought, whereby compact cities and densification strategies have entered mainstream urban planning practice, the market has resisted such approaches, and consumer tastes have persisted for low-density residential land. Developers of suburbia and exurbia continue to subdivide the land and build housing, often creating single-purpose communities. The new urbanists have criticized the physical patterns of suburban development and car-dependent subdivisions that separate malls, workspaces and residential uses by highways and arterial roads. City leaders and planning professionals have responded and greatly enhanced new community design standards. Smart growth is an approach to planning that focuses on rejuvenating inner city areas and older suburbs, remediating brown-fields and, where new suburbs are developed, designing them to be town-centered, transit and pedestrian-oriented, less automobile-dependent and with a mix of housing, commercial and retail uses drawing on cleaner energy and green technologies.

The tension in planning practice needs to be better acknowledged and further discussed if sustainable cities are to be realized. The forces that continue to drive the physical form of many cities, despite the best intentions of planning, present challenges that need to be at the forefront of any discussion on the sustainable development goals of cities. Some pertinent issues, which suggest the need for rethinking past patterns of urbanization and addressing them include:

- Competing jurisdictions between cities, towns and surrounding peri-urban areas whereby authorities compete with each other to attract suburban development

- The actual costs to the economy and society of fragmented land use and car-dependent spatial development; and

- How to come up with affordable alternatives to accommodate the additional 2.5 billion people that would reside in cities by 2050.

In reality, it is mainly these outer suburbs, edge cities and outer city nodes in larger city regions where new economic growth and jobs are being created and where much of this new population will be accommodated, if infill projects and planned extensions are not designed. While densification strategies and more robust compact city planning in existing city spaces will help absorb a portion of this growth, the key challenge facing planners is how to accommodate new growth beyond the existing core and suburbs. This will largely depend on local governments’ ability to overcome fragmentation in local political institutions, and a more coherent legislation and governance framework, which addresses urban complexities spread over different administrative boundaries.