Explaining Socialization

Learning Objective

- Describe the theories of Cooley, Mead, Freud, Piaget, Kohlberg, Gilligan, and Erikson.

Because socialization is so important, scholars in various fields have tried to understand how and why it occurs, with different scholars looking at different aspects of the process. Their efforts mostly focus on infancy, childhood, and adolescence, which are the critical years for socialization, but some have also looked at how socialization continues through the life course. Let’s examine some of the major theories of socialization, which are summarized in Table 4.1 “Theory Snapshot”.

Table 4.1 Theory Snapshot

| Theory | Major figure(s) | Major assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| Looking-glass self | Charles Horton Cooley | Children gain an impression of how people perceive them as the children interact with them. In effect, children “see” themselves when they interact with other people, as if they are looking in a mirror. Individuals use the perceptions that others have of them to develop judgments and feelings about themselves. |

| Taking the role of the other | George Herbert Mead | Children pretend to be other people in their play and in so doing learn what these other people expect of them. Younger children take the role of significant others, or the people, most typically parents and siblings, who have the most contact with them; older children when they play sports and other games take on the roles of other people and internalize the expectations of the generalized other, or society itself. |

| Psychoanalytic | Sigmund Freud | The personality consists of the id, ego, and superego. If a child does not develop normally and the superego does not become strong enough to overcome the id, antisocial behavior may result. |

| Cognitive development | Jean Piaget | Cognitive development occurs through four stages. The final stage is the formal operational stage, which begins at age 12 as children begin to use general principles to resolve various problems. |

| Moral development | Lawrence Kohlberg, Carol Gilligan | Children develop their ability to think and act morally through several stages. If they fail to reach the conventional stage, in which adolescents realize that their parents and society have rules that should be followed because they are morally right to follow, they might well engage in harmful behavior. Whereas boys tend to use formal rules to decide what is right or wrong, girls tend to take personal relationships into account. |

| Identity development | Erik Erikson | Identity development encompasses eight stages across the life course. The fifth stage occurs in adolescence and is especially critical because teenagers often experience an identity crisis as they move from childhood to adulthood. |

Sociological Explanations: The Development of the Self

One set of explanations, and the most sociological of those we discuss, looks at how the self, or one’s identity, self-concept, and self-image, develops. These explanations stress that we learn how to interact by first interacting with others and that we do so by using this interaction to gain an idea of who we are and what they expect of us.

Charles Horton Cooley

Among the first to advance this view was Charles Horton Cooley (1864–1929), who said that by interacting with other people we gain an impression of how they perceive us. In effect, we “see” ourselves when we interact with other people, as if we are looking in a mirror when we are with them. Cooley (1902) developed his famous concept of the looking-glass self to summarize this process. Cooley said we first imagine how we appear to others and then imagine how they think of us and, more specifically, whether they are evaluating us positively or negatively. We then use these perceptions to develop judgments and feelings about ourselves, such as pride or embarrassment.

Sometimes errors occur in this complex process, as we may misperceive how others regard us and develop misguided judgments of our behavior and feelings. For example, you may have been in a situation where someone laughed at what you said, and you thought they were mocking you, when in fact they just thought you were being funny. Although you should have interpreted their laughter positively, you interpreted it negatively and probably felt stupid or embarrassed.

Charles Horton Cooley wrote that we gain an impression of ourselves by interacting with other people. By doing so, we “see” ourselves as if we are looking in a mirror when we are with them. Cooley developed his famous concept of the looking-glass self to summarize this process.

Helena Perez García – The Looking Glass – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Whether errors occur or not, the process Cooley described is especially critical during childhood and adolescence, when our self is still in a state of flux. Imagine how much better children on a sports team feel after being cheered for making a great play or how children in the school band feel after a standing ovation at the end of the band’s performance. If they feel better about themselves, they may do that much better next time. For better or worse, the reverse is also true. If children do poorly on the sports field or in a school performance and the applause they hoped for does not occur, they may feel dejected and worse about themselves and from frustration or anxiety perform worse the next time around.

Yet it is also true that the looking-glass-self process affects us throughout our lives. By the time we get out of late adolescence and into our early adult years, we have very much developed our conception of our self, yet this development is never complete. As young, middle-aged, or older adults, we continue to react to our perceptions of how others view us, and these perceptions influence our conception of our self, even if this influence is often less than was true in our younger years. Whether our social interaction is with friends, relatives, coworkers, supervisors, or even strangers, our self continues to change.

George Herbert Mead

Another scholar who discussed the development of the self was George Herbert Mead (1863–1931), a founder of the field of symbolic interactionism discussed in Chapter 1 “Sociology and the Sociological Perspective”. Mead’s (1934) main emphasis was on children’s playing, which he saw as central to their understanding of how people should interact. When they play, Mead said, children take the role of the other. This means they pretend to be other people in their play and in so doing learn what these other people expect of them. For example, when children play house and pretend to be their parents, they treat their dolls the way they think their parents treat them. In so doing, they get a better idea of how they are expected to behave. Another way of saying this is that they internalize the expectations other people have of them.

Younger children, said Mead, take the role of significant others, or the people, most typically parents and siblings, who have the most contact with them. Older children take on the roles of other people and learn society’s expectations as a whole. In so doing, they internalize the expectations of what Mead called the generalized other, or society itself.

This whole process, Mead wrote, involves several stages. In the imitation stage, infants can only imitate behavior without really understanding its purposes. If their parents rub their own bellies and laugh, 1-year-olds may do likewise. After they reach the age of 3, they are in the play stage. Here most of their play is by themselves or with only one or two other children, and much of it involves pretending to be other people: their parents, teachers, superheroes, television characters, and so forth. In this stage they begin taking the role of the other. Once they reach age 6 or 7, or roughly the time school begins, the games stage begins, and children start playing in team sports and games. The many players in these games perform many kinds of roles, and they must all learn to anticipate the actions of other members of their team. In so doing, they learn what is expected of the roles all team members are supposed to play and by extension begin to understand the roles society wants us to play, or to use Mead’s term, the expectations of the generalized other.

Mead felt that the self has two parts, the I and the me. The I is the creative, spontaneous part of the self, while the me is the more passive part of the self stemming from the internalized expectations of the larger society. These two parts are not at odds, he thought, but instead complement each other and thus enhance the individual’s contributions to society. Society needs creativity, but it also needs at least some minimum of conformity. The development of both these parts of the self is important not only for the individual but also for the society to which the individual belongs.

Social-Psychological Explanations: Personality and Cognitive and Moral Development

A second set of explanations is more psychological, as it focuses on the development of personality, cognitive ability, and morality.

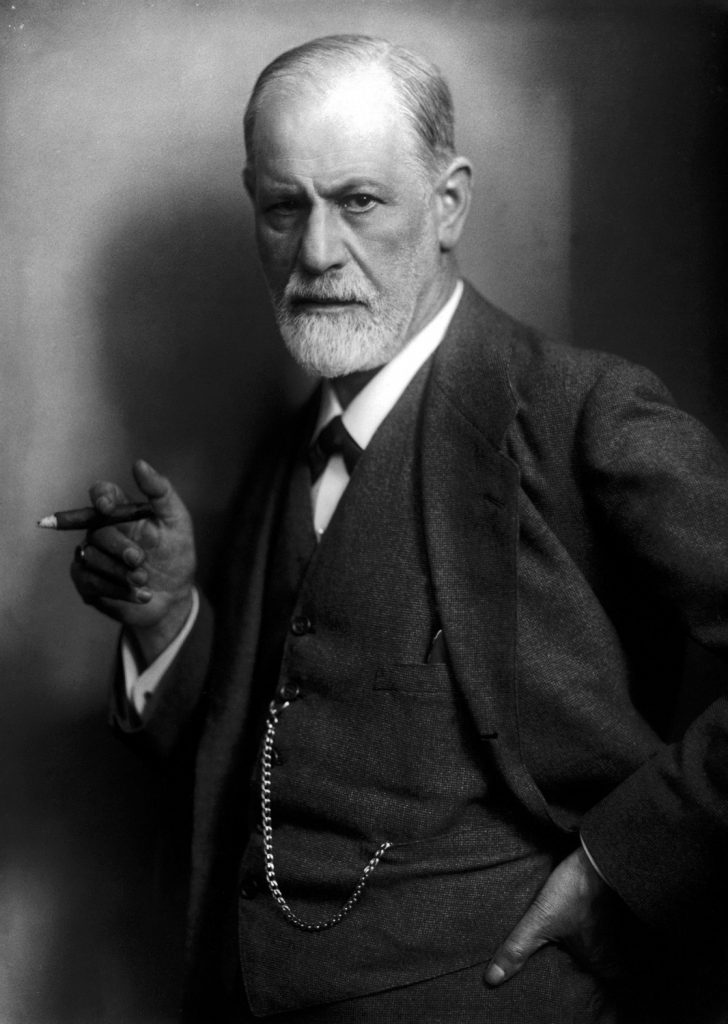

Sigmund Freud and the Unconscious Personality

Whereas Cooley and Mead focused on interaction with others in explaining the development of the self, the great psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) focused on unconscious, biological forces that he felt shape individual personality. Freud (1933) thought that the personality consists of three parts: the id, ego, and superego. The id is the selfish part of the personality and consists of biological instincts that all babies have, including the need for food and, more generally, the demand for immediate gratification. As babies get older, they learn that not all their needs can be immediately satisfied and thus develop the ego, or the rational part of the personality. As children get older still, they internalize society’s norms and values and thus begin to develop their superego, which represents society’s conscience. If a child does not develop normally and the superego does not become strong enough, the individual is more at risk for being driven by the id to commit antisocial behavior.

Sigmund Freud believed that the personality consists of three parts: the id, ego, and superego. The development of these biological forces helps shape an individual’s personality.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Freud’s basic view that an individual’s personality and behavior develop largely from within differs from sociology’s emphasis on the social environment. That is not to say his view is wrong, but it is to say that it neglects the many very important influences highlighted by sociologists.

Piaget and Cognitive Development

Children acquire a self and a personality but they also learn how to think and reason. How they acquire such cognitive development was the focus of research by Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget (1896–1980). Piaget (1954) thought that cognitive development occurs through four stages and that proper maturation of the brain and socialization were necessary for adequate development.

The first stage is the sensorimotor stage, in which infants cannot really think or reason and instead use their hearing, vision, and other senses to discover the world around them. The second stage is the preoperational stage, lasting from about age 2 to age 7, in which children begin to use symbols, especially words, to understand objects and simple ideas. The third stage is the concrete operational stage, lasting from about age 7 to age 11 or 12, in which children begin to think in terms of cause and effect but still do not understand underlying principles of fairness, justice, and related concepts. The fourth and final stage is the formal operational stage, which begins about the age of 12. Here children begin to think abstractly and use general principles to resolve various problems.

Recent research supports Piaget’s emphasis on the importance of the early years for children’s cognitive development. Scientists have found that brain activity develops rapidly in the earliest years of life. Stimulation from a child’s social environment enhances this development, while a lack of stimulation impairs it. Children whose parents or other caregivers routinely play with them and talk, sing, and read to them have much better neurological and cognitive development than other children (Riley, San Juan, Klinkner, & Ramminger, 2009). By providing a biological basis for the importance of human stimulation for children, this research underscores both the significance of interaction and the dangers of social isolation. For both biological and social reasons, socialization is not fully possible without extensive social interaction.

Kohlberg, Gilligan, and Moral Development

An important part of children’s reasoning is their ability to distinguish right from wrong and to decide on what is morally correct to do. Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg (1927–1987) said that children develop their ability to think and act morally through several stages. In the preconventional stage, young children equate what is morally right simply to what keeps them from getting punished. In the conventional stage, adolescents realize that their parents and society have rules that should be followed because they are morally right to follow, not just because disobeying them leads to punishment. At the postconventional stage, which occurs in late adolescence and early adulthood, individuals realize that higher moral standards may supersede those of their own society and even decide to disobey the law in the name of these higher standards. If people fail to reach at least the conventional stage, Kohlberg (1969) said, they do not develop a conscience and instead might well engage in harmful behavior if they think they will not be punished. Incomplete moral development, Kohlberg concluded, was a prime cause of antisocial behavior.

Carol Gilligan believes that girls take personal relationships into account during their moral development.

Vladimir Pustovit – Girls – CC BY 2.0.

One limitation of Kohlberg’s research was that he studied only boys. Do girls go through similar stages of moral development? Carol Gilligan (1982) concluded that they do not. Whereas boys tend to use formal rules to decide what is right or wrong, she wrote, girls tend to take personal relationships into account. If people break a rule because of some important personal need or because they are trying to help someone, then their behavior may not be wrong. Put another way, males tend to use impersonal, universalistic criteria for moral decision making, whereas females tend to use more individual, particularistic criteria.

An example from children’s play illustrates the difference between these two forms of moral reasoning. If boys are playing a sport, say basketball, and a player says he was fouled, they may disagree—sometimes heatedly—over how much contact occurred and whether it indeed was enough to be a foul. In contrast, girls in a similar situation may decide in the interest of having everyone get along to call the play a “do-over.”

Erikson and Identity Development

We noted earlier that the development of the self is not limited to childhood but instead continues throughout the life span. More generally, although socialization is most important during childhood and adolescence, it, too, continues throughout the life span. Psychologist Erik Erikson (1902–1990) explicitly recognized this central fact in his theory of identity development (Erikson, 1980). This sort of development, he said, encompasses eight stages of life across the life course. In the first four stages, occurring in succession from birth to age 12, children ideally learn trust, self-control, and independence and also learn how to do tasks whose complexity increases with their age. If all this development goes well, they develop a positive identity, or self-image.

The fifth stage occurs in adolescence and is especially critical, said Erikson, because teenagers often experience an identity crisis. This crisis occurs because adolescence is a transition between childhood and adulthood: adolescents are leaving childhood but have not yet achieved adulthood. As they try to work through all the complexities of adolescence, teenagers may become rebellious at times, but most eventually enter young adulthood with their identities mostly settled. Stages 6, 7, and 8 involve young adulthood, middle adulthood, and late adulthood, respectively. In each of these stages, people’s identity development is directly related to their family and work roles. In late adulthood, people reflect on their lives while trying to remain contributing members of society. Stage 8 can be a particularly troubling stage for many people, as they realize their lives are almost over.

Erikson’s research helped stimulate the further study of socialization past adolescence, and today the study of socialization during the years of adulthood is burgeoning. We return to adulthood in Chapter 4 “Socialization”, Section 4.4 “Socialization Through the Life Course” and address it again in the discussion of age and aging in Chapter 12 “Aging and the Elderly”.

Key Takeaways

- Cooley and Mead explained how one’s self-concept and self-image develop.

- Freud focused on the need to develop a proper balance among the id, ego, and superego.

- Piaget wrote that cognitive development among children and adolescents occurs from four stages of social interaction.

- Kohlberg wrote about stages of moral development and emphasized the importance of formal rules, while Gilligan emphasized that girls’ moral development takes into account personal relationships.

- Erikson’s theory of identity development encompasses eight stages, from infancy through old age.

Self Check

References

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Social organization. New York, NY: Scribner’s.

Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. New York, NY: Norton.

Freud, S. (1933). New introductory lectures on psycho-analysis. New York, NY: Norton.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kohlberg, L. (1969). States in the development of moral thought and action. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Riley, D., San Juan, R. R., Klinkner, J., & Ramminger, A. (2009). Intellectual development: Connecting science and practice in early childhood settings. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.

our reflection of how we think we appear to others.

the people, most typically parents and siblings, who have the most contact with us in our childhood socialization.