Theories of Population Growth and Decline

Learning Objectives

- Understand demographic transition theory and how it compares with the views of Thomas Malthus.

- Explain why there is less concern about population growth now than there was a generation ago.

- Explain what pronatalism means.

Now that you are familiar with some basic demographic concepts, we can discuss population growth and decline in more detail. Three of the factors just discussed determine changes in population size: fertility (crude birth rate), mortality (crude death rate), and net migration. The natural growth rate is simply the difference between the crude birth rate and the crude death rate. The U.S. natural growth rate is about 0.6% (or 6 per 1,000 people) per year (Rosenberg, 2009). When immigration is also taken into account, the total population growth rate has been almost 1.0% per year (Jacobsen & Mather, 2010).

Figure 19.6 “International Annual Population Growth Rates (%), 2005–2010” depicts the annual population growth rate (including both natural growth and net migration) of all the nations in the world. Note that many African nations are growing by at least 3% per year or more, while most European nations are growing by much less than 1% or are even losing population, as discussed earlier. Overall, the world population is growing by about 80 million people annually.

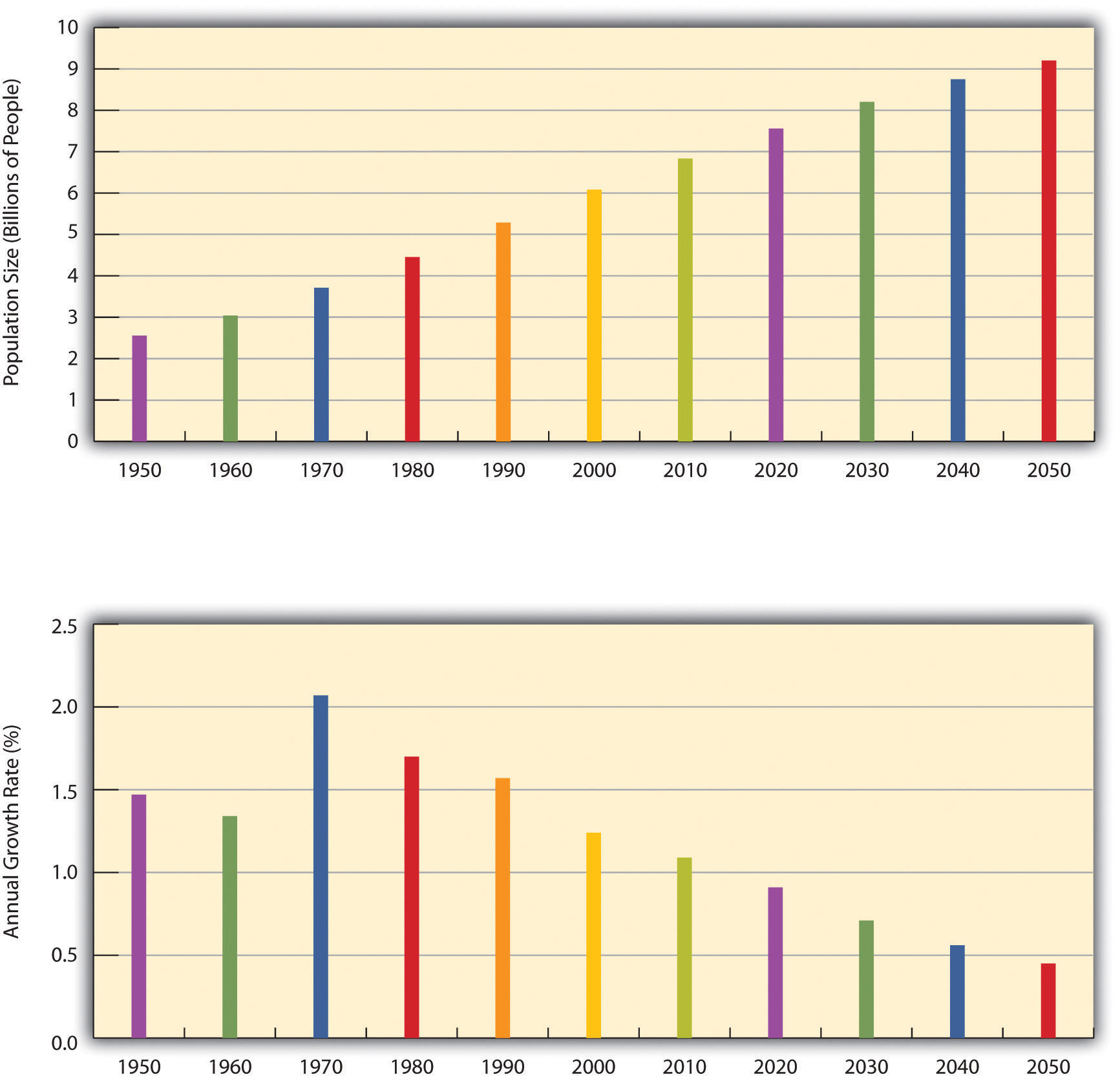

We saw evidence of this pattern when we looked at world population growth. When agricultural societies developed some 12,000 years ago, only about 8 million people occupied the planet. This number had reached about 300 million about 2,100 years ago, and by the 15th century it was still only about 500 million. It finally reached 1 billion by about 1850 and by 1950, only a century later, had doubled to 2 billion. Just 50 years later, it tripled to more than 6.8 billion, and it is projected to reach more than 9 billion by 2050 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010) (see Figure 19.7 “Total World Population, 1950–2050”).

Figure 19.7 Total World Population, 1950–2050

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab.

Eventually, however, population growth begins to level off after exploding, as explained by demographic transition theory, discussed later. We see this in the bottom half of Figure 19.7 “Total World Population, 1950–2050”, which shows the average annual growth rate for the world’s population. This rate has declined over the last few decades and is projected to further decline over the next four decades. This means that while the world’s population will continue to grow during the foreseeable future, it will grow by a smaller rate as time goes by. As Figure 19.6 “International Annual Population Growth Rates (%), 2005–2010” suggested, the growth that does occur will be concentrated in the poor nations in Africa and some other parts of the world. Still, even there the average number of children a woman has in her lifetime dropped from six a generation ago to about three today.

Theories of Population Growth

Malthusian Theory

Thomas Malthus, an English economist who lived about 200 years ago, wrote that population increases geometrically while food production increases only arithmetically. These understandings led him to predict mass starvation.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) was an English clergyman who made dire predictions about earth’s ability to sustain its growing population. According to Malthusian theory, three factors would control human population that exceeded the earth’s carrying capacity, or how many people can live in a given area considering the amount of available resources. Malthus identified these factors as war, famine, and disease (Malthus 1798). He termed them “positive checks” because they increase mortality rates, thus keeping the population in check. They are countered by “preventive checks,” which also control the population but by reducing fertility rates; preventive checks include birth control and celibacy. Thinking practically, Malthus saw that people could produce only so much food in a given year, yet the population was increasing at an exponential rate. Eventually, he thought people would run out of food and begin to starve. They would go to war over increasingly scarce resources and reduce the population to a manageable level, and then the cycle would begin anew.

Of course, this has not exactly happened. The human population has continued to grow long past Malthus’s predictions. So what happened? Why didn’t we die off? There are three reasons sociologists believe we are continuing to expand the population of our planet. First, technological increases in food production have increased both the amount and quality of calories we can produce per person. Second, human ingenuity has developed new medicine to curtail death from disease. Finally, the development and widespread use of contraception and other forms of family planning have decreased the speed at which our population increases. But what about the future? Some still believe Malthus was correct and that ample resources to support the earth’s population will soon run out.

Zero Population Growth

Calls during the 1970s for zero population growth (ZPG) population control stemmed from concern that the planet was becoming overpopulated and that food and other resources would soon be too meager to support the world’s population.

James Cridland – Crowd – CC BY 2.0.

A neo-Malthusian researcher named Paul Ehrlich brought Malthus’s predictions into the twentieth century. However, according to Ehrlich, it is the environment, not specifically the food supply, that will play a crucial role in the continued health of planet’s population (Ehrlich 1968). Ehrlich’s ideas suggest that the human population is moving rapidly toward complete environmental collapse, as privileged people use up or pollute a number of environmental resources such as water and air. He advocated for a goal of zero population growth (ZPG), in which the number of people entering a population through birth or immigration is equal to the number of people leaving it via death or emigration. While support for this concept is mixed, it is still considered a possible solution to global overpopulation.

Fortunately, Malthus and ZPG advocates were wrong to some degree. Although population levels have certainly soared, the projections show that the rate of increase is slowing. Among other factors, the development of more effective contraception, especially the birth control pill, has limited population growth in the industrial world and, increasingly, in poorer nations. Food production has also increased by a much greater amount than Malthus and ZPG advocates predicted. Concern about overpopulation growth has weakened, as the world’s resources seem to be standing up to population growth. Widespread hunger in Africa and other regions does exist, with hundreds of millions of people suffering from hunger and malnutrition, but many experts attribute this problem not to overpopulation and lack of food but rather to problems in distributing the sufficient amount of food that exists.

Another factor might have played a role in weakening advocacy for ZPG: criticism by people of color that ZPG was directed largely at their ranks and smacked of racism. The call for population control, they said, was a disguised call for controlling the growth of their own populations and thus reducing their influence (Kuumba, 1993). Although the merits of this criticism have been debated, it may have still served to mute ZPG advocacy.

Cornucopian Theory

Of course, some theories are less focused on the pessimistic hypothesis that the world’s population will meet a detrimental challenge to sustaining itself. Cornucopian theory scoffs at the idea of humans wiping themselves out; it asserts that human ingenuity can resolve any environmental or social issues that develop. As an example, it points to the issue of food supply. If we need more food, the theory contends, agricultural scientists will figure out how to grow it, as they have already been doing for centuries. After all, in this perspective, human ingenuity has been up to the task for thousands of years and there is no reason for that pattern not to continue (Simon 1981).

Demographic Transition Theory

Other dynamics also explain why population growth did not rise at the geometric rate that Malthus had predicted and is even slowing. The view explaining these dynamics is called demographic transition theory (Weeks, 2012), mentioned earlier. This theory links population growth to the level of technological development across three stages of social evolution. In the first stage, coinciding with preindustrial societies, the birth rate and death rate are both high. The birth rate is high because of the lack of contraception and the several other reasons cited earlier for high fertility rates, and the death rate is high because of disease, poor nutrition, lack of modern medicine, and other problems. These two high rates cancel each other out, and little population growth occurs.

In the second stage, coinciding with the development of industrial societies, the birth rate remains fairly high, owing to the lack of contraception and a continuing belief in the value of large families, but the death rate drops because of several factors, including increased food production, better sanitation, and improved medicine. Because the birth rate remains high but the death rate drops, population growth takes off dramatically.

In the third stage, the death rate remains low, but the birth rate finally drops as families begin to realize that large numbers of children in an industrial economy are more of a burden than an asset. Another reason for the drop is the availability of effective contraception. As a result, population growth slows, and, as we saw earlier, it has become quite low or even gone into a decline in several industrial nations.

Demographic transition theory, then, gives us more reason to be cautiously optimistic regarding the threat of overpopulation: as poor nations continue to modernize—much as industrial nations did 200 years ago—their population growth rates should start to decline. Still, population growth rates in poor nations continue to be high, and, as the “Sociology Making a Difference” box discussed, inequalities in food distribution allow rampant hunger to persist. Hundreds of thousands of women die in poor nations each year during pregnancy and childbirth. Reduced fertility would save their lives, in part because their bodies would be healthier if their pregnancies were spaced farther apart (Schultz, 2008). Although world population growth is slowing, then, it is still growing too rapidly in much of the developing and least developed worlds. To reduce it further, more extensive family-planning programs are needed, as is economic development in general.

Population Decline and Pronatalism

Still another reason for the reduced concern over population growth is that birth rates in many industrial nations have slowed considerably. Some nations are even experiencing population declines, while several more are projected to have population declines by 2050 (Goldstein, Sobotka, & Jasilioniene, 2009). For a country to maintain its population, the average woman needs to have 2.1 children, the replacement level for population stability. But several industrial nations, not including the United States, are far below this level. Increased birth control is one reason for their lower fertility rates but so are decisions by women to stay in school longer, to go to work right after their schooling ends, and to not have their first child until somewhat later.

Spain is one of several European nations that have been experiencing a population decline because of lower birth rates. Like some other nations, Spain has adopted pronatalist policies to encourage people to have more children; it provides 2,500 euros, about $3,400, for each child.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 3.0.

Ironically, these nations’ population declines have begun to concern demographers and policymakers (Shorto, 2008). Because people in many industrial nations are living longer while the birth rate drops, these nations are increasingly having a greater proportion of older people and a smaller proportion of younger people. In several European nations, there are more people 61 or older than 19 or younger. As this trend continues, it will become increasingly difficult to take care of the health and income needs of so many older persons, and there may be too few younger people to fill the many jobs and provide the many services that an industrial society demands. The smaller labor force may also mean that governments will have fewer income tax dollars to provide these services.

To deal with these problems, several governments have initiated pronatalist policies aimed at encouraging women to have more children. In particular, they provide generous child-care subsidies, tax incentives, and flexible work schedules designed to make it easier to bear and raise children, and some even provide couples outright cash payments when they have an additional child. Russia in some cases provides the equivalent of about $9,000 for each child beyond the first, while Spain provides 2,500 euros (equivalent to about $3,400) for each child (Haub, 2009).

Key Takeaways

- Concern over population growth has declined for at least three reasons. First, there is increasing recognition that the world has an adequate supply of food. Second, people of color have charged that attempts to limit population growth were aimed at their own populations. Third, several European countries have actually experienced population decline.

- Demographic transition theory links population growth to the level of technological development across three stages of social evolution. In preindustrial societies, there is little population growth; in industrial societies, population growth is high; and in later stages of industrial societies, population growth slows.

For Your Review

- Before you read this chapter, did you think that food scarcity was the major reason for world hunger today? Why do you think a belief in food scarcity is so common among Americans?

- Do you think nations with low birth rates should provide incentives for women to have more babies? Why or why not?

References

Ehrlich, P. R. (1969). The population bomb. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club.

Goldstein, J. R., Sobotka, T., & Jasilioniene, A. (2009). The end of “lowest-low” fertility? Population & Development Review, 35(4), 663–699. doi:10.1111/j.1728–4457.2009.00304.x.

Haub, C. (2009). Birth rates rising in some low birth-rate countries. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.prb.org/Articles/2009/fallingbirthrates.aspx.

Jacobsen, L. A., & Mather, M. (2010). U.S. economic and social trends since 2000. Population Bulletin, 65(1), 1–20.

Kuumba, M. B. (1993). Perpetuating neo-colonialism through population control: South Africa and the United States. Africa Today, 40(3), 79–85.

Malthus, T. R. (1926). First essay on population. London, England: Macmillan. (Original work published 1798).

Rosenberg, M. (2009). Population growth rates. Retrieved from http://geography.about.com/od/populationgeography/a/populationgrow.htm.

Scanlan, S. J., Jenkins, J. C., & Peterson, L. (2010). The scarcity fallacy. Contexts, 9(1), 34–39.

Schultz, T. P. (2008). Population policies, fertility, women’s human capital, and child quality. In T. P. Schultz & J. Strauss (Eds.), Handbook of development economics (Vol. 4, pp. 3249–3303). Amsterdam, Netherlands: North-Holland, Elsevier.

Shorto, R. (2008, June 2). No babies? The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/29/magazine/29Birth-t.html?scp=1&sq=&st=nyt.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab.

Weeks, J. R. (2012). Population: An introduction to concepts and issues (11th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.